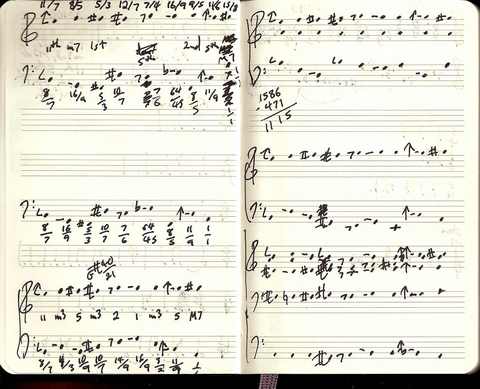

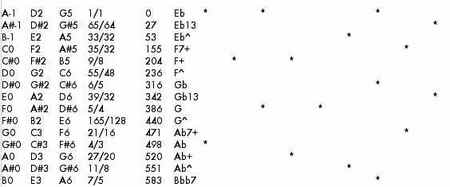

I have to say, this has become one of the most richly fulfilling summers I’ve ever had. On one hand I’ve done all this work on piano recordings by Harold Budd and Dennis Johnson, plus a long John Luther Adams analysis I’m finishing and my Robert Ashley biography (3000 words written today, after hours of composing); on the other, recording my piece The Planets with Relache, and then a slew of music rushing out of me lately, with a ten-minute microtonal piece written this week (of which more soon), and two other new pieces begun in the same span.

Cage wrote a mesostic for Nancarrow that reads, “oNce you / sAid / wheN you thought of / musiC, / you Always / thought of youR own / neveR / Of anybody else’s. / that’s hoW it happens.” I think I probably could have been as reclusive as Nancarrow, had not economic necessity forced me into the public life of music criticism. But I certainly am not like Nancarrow in this other respect. A life exclusively focused on my own music seems unimaginable. My musicological work feeds my composition, and vice versa. When I’ve been doing too much critical work and not composing, I get cranky; and when I’ve been composing continuously, I dry up a little, and I start to need the interaction with the music of others. It’s not that I steal so many ideas from other composers, though of course I never scruple to do that. Nothing about the other people’s music I’m working on went into the piece I just finished, though I do absorb inspiration from the brilliant things Ashley says, and Budd always reconfirms my love for the major seventh chord. I just need that rejuvenation from other artist’s ideas, the mere presence of simpatico music I didn’t write.

I seem not to be unique in this respect among my close contemporaries. Larry Polansky, a far more prolific composer than myself, has done loads of important musicological work on Ruth Crawford, Johanna Beyer, and Harry Partch, not to mention running Frog Peak Music for the publishing of other composers’ music. Peter Garland, in between writing his own wonderful pieces, published the crucial Soundings journal for many years, and made available the music of many who didn’t seem so obviously important at the time as they do now. Some of us need this close interaction with the music of our contemporaries. Nor does it seem like just an American thing. Schumann certainly spent a lot of his career inside other composers’ heads, and seems to have enjoyed having a trunkload of Schubert’s manuscripts in his apartment, from which to draw for the occasional world premiere whenever he fancied. Liszt played the piano music of every significant contemporary except Brahms (who offended him by falling asleep at the premiere of Liszt’s B minor Sonata).

Part of it is what I think Henry Cowell sensed: that there’s no such thing as a famous composer in a musical genre no one’s heard of, and so one’s personal survival depends on a rising tide raising all boats. But Morton Feldman also tells a story of an artist in the ’50s who, after seeing Jackson Pollock’s first astounding exhibition of drip paintings, remarked, “I’m so glad he did it. Now I don’t have to.” And Feldman adds, for thoughtful emphasis, “That was not an extraordinary thing to say at the time.” Some of us do have this feeling that art is a collective activity, that it’s not all about ourselves. I hear an exquisite piece like John Luther Adams’s The Light Within, and I do think, somehow, “I’m so glad he did it, now I don’t have to” – partly because I want to hear that kind of ecstatic wall-of-sound genre, and he can so it much better than I could. Mikel Rouse’s music is so much more sophisticated than my intentionally naive fare, but listening to him gets me back on track. I listen to Eve Beglarian’s music, and I hear things I might have been tempted to do, but she’s got them covered. These aesthetically close colleagues free me up to pursue what I do best, but I somehow need to participate in their achievements by analyzing them and writing about them.Â

We Americans are taught to worship individuality, in art above all, but there is a strong collective aspect to creativity that many composers strenuously ignore or deny. I have no idea why I’m so attuned to it, especially being as anti-social as I am by temperament. But I do know that if anyone ever regrets that I had to write all these books and articles instead of working non-stop on my own music, they will have missed the point. It’s all the same thing.