My profile of composer Julia Wolfe is out in Chamber Music magazine this week.

Archives for June 2009

A Little Slow with the Index Cards

Speaking of Robert Ashley, I had a wonderful moment interviewing him a couple of weeks ago. We covered his entire life up to 1979, and then hit Perfect Lives. Of course I think Perfect Lives (then titled Private Parts) was the onset of the spectacular part of Ashley’s career, the moment at which he transcended the post-Cage conceptualist movement he was a player in. The piece will get an entire chapter in my upcoming book. And as we discussed it I learned that I had been involved in the world premiere. On October 24, 1979 – I have the poster for the performance in my living room – Ashley and “Blue” Gene Tyranny came to Northwestern University, at the invitation of my composition teacher Peter Gena, to perform Private Parts in its entirety for the first time. I had forgotten, if I knew then, that this was the first complete performance. Bob, as was his wont, needed a bottle of vodka to drink during the performance. As the grad student go-fer in charge, it was my job to drive in a rush to Desplains, Ill. (since Evanston, home of the Women’s Temperance Union, was a dry town) and buy the vodka. Vodka was a little heady for my taste at the time – a 1994 trip to Warsaw would change that – so, imitating my hero, I picked up a bottle of wine for myself. Bob was then performing the piece by reading the text from a video monitor. Technology being what it then was, the monitor was connected to a backstage camera, and someone had to hold index cards containing the text in front of the camera. That someone was me. So Bob was onstage drinking vodka, “Blue” was playing the piano in his inimitably gorgeous way, and I was backstage sipping wine while moving cards in front of a video camera. At one point late in the piece I was a little slow, and I heard Bob patiently say, in the middle of the text, “Kyle….”Â

Young Avant-Gardists at Play

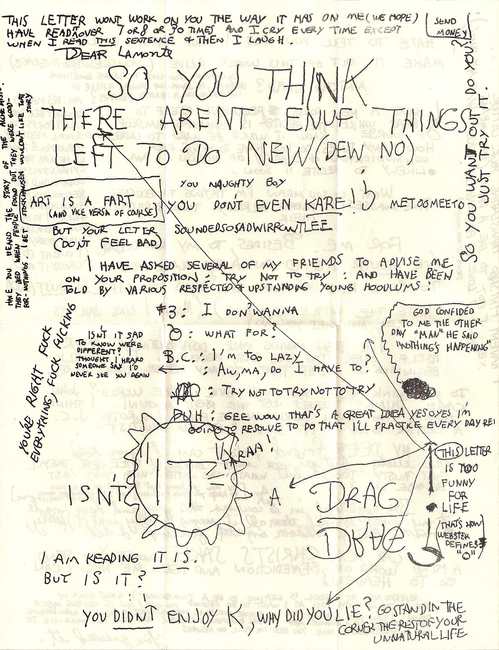

Anyone remember this?

Notating Dennis

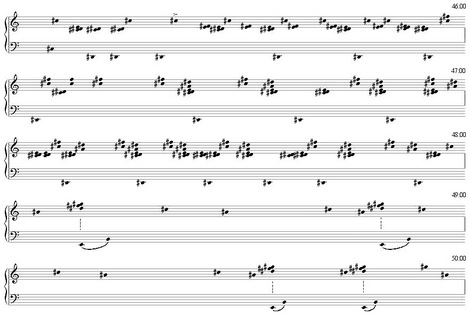

And here’s an mp3 of this passage in the original 1962 recording so you can compare. (I suppose you might have to reopen Postclassic in an additional browser window to listen and follow along at once.) This is one of my favorite moments in the performance, where the relatively dense (by ’50s minimalism standards) section on the dominant of G# minor gives way to a kind of beatific deceptive cadence and much slower material. Each section of the piece, each tonality, has its own atmosphere and tempo that seems drawn from the intervals played around with.

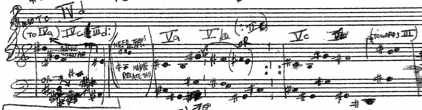

And that’s the problem: you can’t gather that from the original notation. The first three systems above are all drawn from this little bit of Johnson’s score labeled IIIa and IIIb:

Wherever this material recurs, it’s the fastest part of the piece, with a kind of anxious melody leading down from F# to D# to C#. In some notes he apparently made later in the 1980s, Johnson singles this material out to try to figure out what his logical process was, which was a kind of ABACABACDCDB, and so on, among closely related figures. The E major material that follows, on the other hand, doesn’t appear in the manuscript score at all. The piece is intended to be improvised from the scores, and needn’t duplicate the tape; in fact, an alleged four hours is missing from the tape. So neither the score nor the tape is sufficient to construct a performance. Using the score, a pianist could play the work, but only after considerable study of the available 112 minutes on the tape, to find out how Johnson moved from one section to another and how he characterized the material in each section. It’s a peculiarly hybrid form of improvisation, in which you’re limited to what’s on the page, but the page isn’t enough. Hopefully my transcription will yield up enough analytical insight to resurrect some version of the whole thing.

Trying to Remember that Kind of November

I’m almost done transcribing and analyzing Dennis Johnson’s November, the ostensively six-hour 1959 piano piece that La Monte Young says inspired him to embark on The Well-Tuned Piano. I’ve listed some of November‘s innovations elsewhere. If it was indeed the first multi-hour continuous minimalist piece, the first tonal very slow work, the piece that pioneered additive process – and it may have been all that – those in themselves are enough to make it worth reviving and getting into the history books. But beyond that, I’ve become more and more impressed with its internal logic, which is almost mathematical (and Johnson left music to become a mathematician). The piece is organized into families of motifs based on the same pitches, which can proceed improvisatorily to other families of motifs at specified points. Johnson begins each new pitch field additively, bringing in one note or chord, then another, then another until they’re all present. But the overall formal concept is not simply additive but more like a series of circles, as each pitch field has a point of entry and exit, and within each section one can go back and forth among the motifs in that field. It’s really elegant, and in its glacial way makes a certain large-scale sense to the ear. Feldman’s wonderful masterpiece Triadic Memories (a much later work, 1981) is similar in its reminiscent effects and equally intuitive, but November is generally diatonic rather than chromatic, and its logic lies a little closer to the surface. I thought that in September Sarah Cahill and I would be re-premiering a kind of crazy, off-beat experiment of the late ’50s; instead I’m thinking we’ll be unveiling a whole new formal paradigm that deserved to have more of an after-history than it’s had.Â

Slam, Bam, Thank You, Professor

I was told that the committee pretty much had to make a decision that day, and by the time I flew back I already had a “thanks but no thanks” e-mail waiting. It came as a relief: not because I didn’t want the job, nor because anything had made a sour impression on me, but because I would have had to make one of the most momentous decisions of my life with almost no evidence to base it on. It’s like they see teaching jobs as interchangeable posts and expect professors to glide thoughtlessly from school to school as advantage dictates, without homes, families, or roots to put down (and it was explicitly a senior position). One might speculate that the committee spent little time with the candidates because, as happens occasionally at schools everywhere, they already knew who they wanted to hire, and were just going through the motions. If so, however, it would have been wasteful of them to pay to fly me across the Atlantic for a charade; and at one point they were forced to redefine and relist the position, and they asked me to reapply, so I feel certain I was a serious contender.

The only sad thing is that I love England and would love to teach there, but if all their interviews are like this, I can’t imagine that I would ever gain enough confidence from succeeding at one to sell my beautiful, almost-paid-for house and move tens of thousands of compact discs, not to mention books, scores, grand piano, wife, dog, and two cats, across an ocean. And yet I’m not prepared to claim that the English system is inferior to ours, just that it seems counterintuitive. American schools put tremendous, perhaps quixotic, emphasis on assessing collegiality. The longest interview I ever had, at Bard, lasted two and a half days, and I’ve heard of others that ran longer. We want to eat with the candidate, watch him teach, watch him drink, plumb his opinions, see him react to provocation, and in the end, what good does it do? Interviewing at one school, once, I was taken to dinner by two music faculty who proceeded to have a shouting fight with each other, in the restaurant, as I looked on in mute astonishment. At another, early in my career, the chair of the search committee took me to lunch privately, and pressed me at uncomfortable length to reveal my sexual orientation, with the unmistakable implication that he favored bisexuals. (And I’d call that only the third most unpleasant academic interview I’ve ever had.)Â

It’s always struck me as reasonable that marriages had just as much chance of being successful back in the old days, when they were arranged by astrologers and matchmakers with the bride and groom not meeting each other until the wedding, as they do today. Similarly, perhaps the idea that we can gauge collegiality over a three-day interview and predict future compatibility from a tense private breakfast is no more than a hopeful myth. All comparative experience I’ve heard of suggests that a music department, any music department, any academic department, anywhere, gets described by its members as the proverbial nest of vipers in which one will find a few allies, but ultimately learn to keep one’s head down and teach with hope of nothing better than a comparative absence of interference. So perhaps it’s best to get the process of entering one over with as quickly as possible, relying on the most superficial and documentable criteria. Or hell, consult the I Ching for each candidate. As academic interviews go, this one was certainly pleasant and dignified, with no opportunity given for momentary humiliation or discomfort. I have no evidence that the more labor-intensive, touchy-feely American system guarantees more enviable results. But I also feel that, given the exorbitant cost of flying me on short notice to their scepter’d isle, the English faculty were allowed precious little information about me in return.

I do, however, try to discover one new single-malt scotch whenever I visit England, and I came back with a superb 14-year-old Bunnahabhain. (I think the name is Scots dialect for “That’s a smart rabbit,” or “I’m the bane of that rabbit’s existence.”) Of it, Jim Murray’s 2009Â Whisky Bible states, “I thought I noticed it when I tasted it late last year, and earlier this. ‘Where’s that bracing, mildly tart, eye-watering Bunna that I so adore?’ I wondered. Thankfully no sign of the sulphur that caused so many problems for so long. But something, I thought, was missing… I can report there is no shortage of charm and the earliest barley belt on the palate rocks. But the fire has been doused, most probably by caramel.” I can see what he means, but I like caramel, and Bunnahabhain is a luxuriously soothing contrast to my usual more demanding Caol Ila. In 2007 dollars the bottle would have cost me $79, but at today’s exchange rate I was put out only $49. Such delicious revenge was worth an 18-hour round-trip flight.

UPDATE: I have to compliment one side-effect of the British interview process, though, that seemed extremely civilized. Spending the day with the other candidates humanized them. Usually when some asshole gets a job I applied for I assume he’s a Davidovsky protégé who slept with the right grad school teachers and writes music so convoluted that it threatens no one. But here it felt like the five of us were sort of in this together, and I was sincerely happy for the nice guy who was offered the job. That’s never happened before.

Techno-Scammed Again

A couple of years ago, tired of endemic printer problems, I splurged on a big Hewlett Packard Color Laser 2600n. It uses four huge ink cartidges, the black costing $85 and the three color ones $95 each, but I was assured that they held so much ink that they’d last forever and I’d save money in the long run. Now – I print thousands of black-and-white pages a year, and maybe three or four color pages, when I need a Google map. But when the black cartridge runs out on this machine, it seems that I automatically get a message to replace the other ones too, and the machine stops working. So I finally called technical support and got a very nice lady who directed me how to put the machine on “Cartridge Out Override,” or something, though she says it will only work for a couple of weeks. And she explained to me that this machine uses a special “in-line technology,” by which, whenever a page is counted for the black cartridge, one is similarly counted for the cyan, yellow, and magenta cartridges as well. And so it’s built in to the machine, that every time I finish off my black cartridge (or merely every time it clicks off an HP-determined number of allowed pages), I have to go out and pay $370 for four new cartridges. I turned on the “Cartridge Out Override” as she directed, and printed a page in glorious full color: there’s plenty of ink left in those color cartridges that the machine is demanding I replace. I don’t know what’s going to happen after I use the override for two weeks, whether it’s going to turn into a pumpkin or something, but I do know that for $370 every few months I could get a pretty damn nice new printer and treat ’em like disposables.Â

Drawing the Connections

Back in Evanston, Illinois, in the early ’80s, I used to know Evelyn Becker, the widow of composer John J. Becker. Becker is the member of the “American Five” that you can never think of, unless you also can’t remember Wallingford Riegger. Riegger was a Communist, and Mrs. Becker reported that he had scandalized her by writing John letters that began, “Dear Comrade….” “After all,” she shuddered, “we were good Catholics!”

In 1933-34, John Cage moved to New York at Henry Cowell’s advice, to study with Adolph Weiss – but also found himself playing cards with Weiss and Wallingford Riegger. In 1941, a 15-year-old Morton Feldman studied with Riegger. And later in 1952 or ’53, Riegger took a sabbatical replacement position at Manhattan School of Music, where a young Robert Ashley was pursuing his Master’s degree. Ashley and Riegger both had apartments on the East Side, and ended up taking the same bus to school every day. Riegger was the first composition teacher Ashley had found sympathetic, and Ashley remembers being the only kid in class interested in the 12-tone techniques Riegger was teaching. Riegger wrote an astonishing Study in Sonority in 1928, more radical to my ears than anything Schoenberg had yet done, and attractive Third and Fourth Symphonies and a Piano Concerto all in a 12-tone idiom, and also a beautifully retro Canon and Fugue in old-fashioned D minor.Â

I’m not a real music historian, but I’m a sufficiently enthusiastic fake one to get a kick from knowing and drawing these connections. We don’t think, for example, of Cage and Ralph Shapey inhabiting the same scene, but at some point circa 1950 they, along with Feldman, were drawn into the orbit of Stefan Wolpe; and ten years later, we find Wolpe and Cage hobnobbing with Cage’s New School student Toshi Ichiyanagi and his new bride Yoko Ono. Someday there will be a book on James Tenney, who studied with Varese, befriended Ruggles, argued with Partch, made psychedelic eletcronic music with Mort Subotnick, played in the ensembles of Steve Reich and Phil Glass, taught alongside Harold Budd, and taught Peter Garland, Larry Polansky, John Luther Adams, and Michael Byron, among many others. Tenney is a line wandering through American musical history, drawing a variety of unexpected connections. The people most central to American music, those who can’t be pulled out of the fabric without it unraveling, are not always the household names.Â

And so interviewing Ashley (12 hours so far this week) is one of the most exciting things I’ve ever done. He doesn’t like reminiscing about the past – he thinks I should concentrate on his most recent ideas – and doesn’t realize how quietly the history of 20th-century music falls into focus as he tells me about all the contacts he made in his youth. (One thing I learned – Luciano Berio was a wealthy man from the beginning. Why? Heir to the Berio olive oil fortune. I think of Berio every time I see that olive oil in the grocery store, but never knew the connection. [And it’s not true, as it turns out, but Bob, who knew Berio for forty years, thought it was.]) Yesterday, Ashley told me:

“The only thing that’s interesting to me right now is that, up to me and a couple of other guys, music had always been about the eventfulness: like, when things happened, and if they happened, whether they would be a surprise, or an enjoyment, or something like that… It’s about eventfulness. And I was never interested in eventfulness. I was only interested in sound. I mean, just literally, sound in the Morton Feldman sense…. There’s a quality in music that is outside of time, that is not related to time. And that has always fascinated me… That’s sort of what I’m all about, from the first until the most recent. A lot of people are back into eventfulness. But it’s very boring. Eventfulness is really boring.”

It reminded me strongly of when, years ago, La Monte Young showed me his early string quartet in which the five movements are all almost identical, and I asked him why, and after a moment’s musing he responded, “Contrast is for people who can’t write music.” When I quote that there are always people who get defensive and agitated about it, but for many of us, that’s just our aesthetic. It’s not going to replace Mozart, and you’ll still get to hear Stravinsky, and there’s no reason to think that our saying that is the end of the world, and that we have to be smothered, or stopped, or else we’ll bring the whole edifice of culture crashing down. For some of us, eventfulness is boring, contrast is unnecessary, and we’re interested in the aspects of music that don’t relate to time. And the fact that we moved to that in a single generation from Riegger and Wolpe, and that these important threads can be teased out of history, is a tremendously thoughtful pleasure.

UPDATE: McLaren points out in comments that Riegger’s Study in Sonority isn’t currently available in any form. So here it is.Â

When Morty Met Stefan

For instance, in 1980 Austin Clarkson interviewed Morty about his teacher Stefan Wolpe, and asks him about Ernst Krenek:

MF: Well, you see, what Krenek didn’t do, what Stefan did was that he was a competitor. Krenek felt the fact that he had a success when he was young [Jonny Spielt Auf, I assume], and he was married to Schoenberg’s daughter [but see comments], that he was given a crown and he could go and fall asleep with his own ideas for the rest of his life. Wolpe was in the midst of a musical revolution in New York. He was in the midst of the rising young, fabulously talented people coming up in Europe, and he knew it. Krenek never knew it. There’s not an ounce in Krenek’s music, in things that I’ve heard of his late style… But nothing existed, nothing happened. It’s music where nothing happened. It’s the kind of music somebody might write some place in Adelaide, Australia. But Wolpe is caught up in world events, musical events, and things happened…

MF: To show you [Wolpe’s] identification with the avant-garde, he once balled me out, very strongly, for never playing him in our concerts in the early ’50s. The Cage concerts. He balled me out. He was sore. But he did identify with the younger people… which certainly most of his students didn’t. Ralph [Shapey] didn’t, none of his students around him. I don’t know what they identified with. They identified not with Wolpe so much, but the tradition which Wolpe came out of. [p. 107, itals and ellipses in the original]

And, asked about Wolpe’s early interest in Satie:

MF: …I’ll tell you what happened to Satie and the whole idea that independents couldn’t survive in Europe, just couldn’t survive the way they survive here. That some of our strongest people today are independents, where do you put them? Like George Crumb. He was a big influence, and yet he is an independent really. George Crumb couldn’t happen in Europe, essentially. With all the European cliques it couldn’t happen. And so Wolpe added to the whole category of very strong independent composers in America. I think that the best thing is to push him as an American rather than as a European. That way you’ll get a little more mileage, because if you’re going to push him as a European, they’re going to say, well, what is this in relation to… we have this over here, which is what they say. [pp. 107-8]

And how Feldman met Wolpe:

MF: I’ll tell you how I heard about Wolpe. I was just a kid out in Queens. I didn’t know anybody. A friend of mine – I’m not going to mention his name, because his name is known to some degree – thought very highly of himself and sent a score of his to [Dmitri] Mitropolous. Mitropolous saw essentially that he was still a student, even though the young man didn’t think he was still a student, and suggested that he work with Wolpe. I lost my friend, and I was very close to this friend, because he came back and he told me about a visit he had with Wolpe where they just didn’t get along at all, anything that Wolpe had to say. And I listened to this conversation very clinically, and I listened to the things that Wolpe said to my friend, and I gave it a little thought, and three days later I called up Wolpe and asked him if I could come see him. I mean, he sounded to me like a terrific teacher, and I lost a friendship of a young colleague at the time for betraying him. “How could you go to Wolpe after telling how Wolpe insulted me?” But he sounded like a good teacher to me. [laughs] And that was the smartest thing I ever did was to lose that friend and not have that sense of loyalty. [p. 109]

Fascinating and endearing stuff (apologies, though, to any composers in Adelaide). Anyone know who the friend was?

Caution, Slow Listener

That my readers’ defenses of Dvorak are falling on deaf ears says something about my own compositional technique which has been on my mind lately. It’s not that I don’t find Dvorak’s music well crafted, but that his unit of craft is too often the one- or two-measure phrase, bounded by bar-lines. In my own music, I am obsessed with making the bar-line disappear. I don’t have a lot of particular things I pick on students about, but a passage like the one I quoted from the New World Symphony, if a student had brought it to me, would drive me nuts. When I see a kid composing in units of measure, measure, measure, with a new impetus, new phrase, new harmony on every downbeat, I start in with my wheedling tone (every experienced composition student will recognize the sound): “How about a triple upbeat to start that melody off a little more gracefully?” “How about we vary the harmonic rhythm here?” “You think the audience can’t hear where your bar-lines are if you don’t accent every one?”Â

Sic ‘omm!

A site is now up for the Second International Conference on Minimalist Music that David McIntire and I are directing at the University of Missouri at Kansas City September 2-6. You can register, find out about performances, make housing arrangements, and so on. We’ll be adding more details to the site as we firm up the schedule.

Procrastinating with Percy

I don’t care what the airline authorities say, Joe Biden is right. I walked onto the plane in Albany feeling fine, and walked off in Chicago two hours later with a cold. And I heard the guy sneeze behind me, big. Second cold this month, and I always get one when I fly. The dean’s office is waiting for my final grades, but it’s a beautiful summer day out on my screened-in porch. Which raises the question, how do people without blogs get out of doing the work people are expecting from them? Poor excuse-less schmucks must have to keep their noses to the grindstone, even while sneezing their heads off.

Meanwhile, there’s an old, frail copy of an “Analytic Symphony Score” piano reduction of Dvorak’s New World Symphony, which I found at a wonderful little used book store in Great Barrington, sitting on my piano, edited by Percy Goetschius, Mus. Doc. I’m a big fan of Percy Goetschius, Mus. Doc. – I’ve even got the same degree. I collect his theory books, published in the late 19th century (I first found one years ago in Trimpin’s library), and love reading them. They’re bracingly, menacingly hard-core. The fourth scale degree always resolves to the third, the seventh must rise to the octave, a iii6-4 chord can only follow I, and if you brazenly start a modulation with the I (one) chord of the new key as your pivot – well, may God have mercy on your soul, that’s all Percy has to say. In my dreams I imagine teaching a beginning theory class with Percy’s The Theory and Practice of Tone-Relations (1892), but the students would feel like they were on a chain gang. Every piece of music they look at would break Percy’s iron-clad rules, and I’d have a hell of a time finding suitably strict musical examples. And yet, reading him, the reasons music is the way it is fall into place, and random-looking conventions come to seem inescapably logical. There is a reason, generally, to avoid the I chord as a pivot. Probably 98 percent of iii6-4 chords follow I with passing motion in the bass. The essence of music shines forth, isolated in the tight little net of Percy’s mandates. This is a real man’s theory, with none of your current-day liberal mollycoddling.

New World Symphony makes me wish I had taught the piece in the 19th-century course I just completed (the one whose papers I have yet to grade). I’ve never taught Dvorak, not having much use for him (I prefer the 5th, 6th, and 8th symphonies to the 9th, at least), but playing through it, I realize that the first movement of the New World is the most pedantically clear Romantic sonata-allegro I know of. Every melodic phrase is four measures. (Percy says every melody is four measures at heart: maybe two if it’s slow, or eight if it’s fast, and other lengths have to be accounted for by extensions or elisions. It’s easy to see why he liked the New World.) Every four-, two- or one-measure unit gets repeated. Sometimes the tune is the same and the harmony changes, sometimes the notes change but the rhythm is repeated, sometimes the rhythm changes but the pitches are retained, but there’s a fanatical insistence on leading the ear from measure to measure. No measure comes as a surprise, or almost even a contrast.

Really not so far from early minimalist practice, only less gradual and with conventional chord teleology. It’s a smooth, smooth piece, didactically so; a child could make sense of it on first hearing. Its popularity with audiences couldn’t be more explainable. Infinitely inferior to Brahms: one would almost wonder why Brahms so promoted Dvorak’s career, except that it is the immemorial habit of composers to champion other composers whose works are in the same general style as their own but not as good. (An entire history of music could be written elucidating that one principle, especially in the post-WWII era when composers came to run the new-music performance scene.) But the New World – little more than a harmonic progression articulated by repetitious motives – would make a wonderful teaching piece, a template for composing large-scale forms by monotonous formula. The subtle continuities of Brahms, Bruckner, and Mahler are a little too creative and elevated for undergrads to understand, but the New World is right at their level, and assimilating it would make those other composers shine even more brightly. – Kyle Gann, Mus. Doc.

AAAAAAACHHOOOOO!