Very big week for my music coming up next week.

Archives for April 2008

Mi libro finalmente ha aparecido

At long last composer Julio Estrada tells me that my book on Conlon Nancarrow is now available in Spanish, from the University of Mexico Press. I’m awaiting a copy in the mail. Here (in the right column) is the only advertisement I can find for it. Espero que seas ayudado por esta publicación.

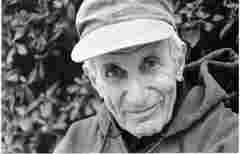

Henry Brant (1913-2008)

Neely Bruce informs me that the great Henry Brant has died within the last few hours. He was a phenomenally creative figure, though one hard to wrap one’s ears around, because his specialty was spatial music; his works, often involving multiple ensembles separated by distance, were too enormous to stage often, and recordings hardly do them justice. I was privileged to have heard his 500: Hidden Hemisphere live, a mammoth piece in celebration of Columbus for three wind ensembles and steel drum band, placed around the fountain at Lincoln Center in 1992. He was born in Montreal, and thus Canada gets to claim him, but his primary inspiration was Charles Ives, and he began composing for instruments widely separated from each other in an attempt to clarify dense, Ivesian polyphony. Even when not writing spatially he composed for unconventional ensembles, like the ten variously sized flutes of his delightful Angels and Devils (1931), or his Orbits (1979) for 80 trombones, organ, and sopranino voice. A work called Fire on the Amstel employs four boatloads of 25 flutes each, four jazz drummers, four church carillons, three brass bands, three choruses, and four street organs. Live performances of it remain rare, for some reason. His reputation as an incredible orchestrator (he made part of his living doing filmscores from the 1930s through ’60s, but didn’t like to talk about them) was confirmed with his 1994 orchestration of Ives’s Concord Sonata, titled A Concord Symphony, a splendid reimagining of a great work.Â

Neely Bruce informs me that the great Henry Brant has died within the last few hours. He was a phenomenally creative figure, though one hard to wrap one’s ears around, because his specialty was spatial music; his works, often involving multiple ensembles separated by distance, were too enormous to stage often, and recordings hardly do them justice. I was privileged to have heard his 500: Hidden Hemisphere live, a mammoth piece in celebration of Columbus for three wind ensembles and steel drum band, placed around the fountain at Lincoln Center in 1992. He was born in Montreal, and thus Canada gets to claim him, but his primary inspiration was Charles Ives, and he began composing for instruments widely separated from each other in an attempt to clarify dense, Ivesian polyphony. Even when not writing spatially he composed for unconventional ensembles, like the ten variously sized flutes of his delightful Angels and Devils (1931), or his Orbits (1979) for 80 trombones, organ, and sopranino voice. A work called Fire on the Amstel employs four boatloads of 25 flutes each, four jazz drummers, four church carillons, three brass bands, three choruses, and four street organs. Live performances of it remain rare, for some reason. His reputation as an incredible orchestrator (he made part of his living doing filmscores from the 1930s through ’60s, but didn’t like to talk about them) was confirmed with his 1994 orchestration of Ives’s Concord Sonata, titled A Concord Symphony, a splendid reimagining of a great work.Â

Truly Arcane Theory Joke

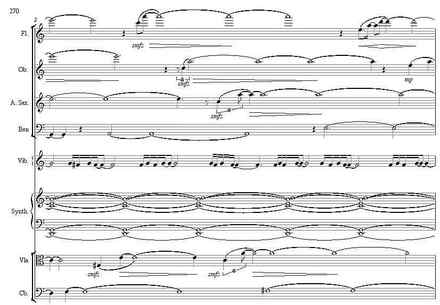

This afternoon we were analyzing movement VII of the Quartet for the End of Time, and came upon a passage using, for the only time in the piece, the following mode of limited transposition, which I asked the class to identify:

Spaced Out

OK. I’ve finished The Planets, and so I’m listening, once again for the 30th time, to John Coltrane’s closely related Interstellar Space album, with just himself and Rashied Ali on drums. I love Coltrane, of course, as who doesn’t? Black Pearls, A Love Supreme, Ascension, Giant Steps, My Favorite Things, Ballads, they’re all among my favorite jazz albums. But Interstellar Space I admit I have trouble figuring out. Mars and Venus should be polar opposites, but I have trouble finding much variety of mood or method on this CD. What am I missing? Postclassic is possibly not the right venue, but can anyone tell me how to listen to this last Coltrane disc (1967) and find it as wonderful as his earlier work?Â

The Rock Need Not Return to Earth

The Stefan Wolpe Society has just sent out its 2007 newsletter (PDF), which is worth reading if you like Wolpe’s music. I do, immensely. Of all the modernist-atonalists of the mid-century, he was my favorite, yet of all the composers whose music I’m nuts about, his is the most difficult to justify to people who don’t get it. I think of his as the music I wanted Elliott Carter’s to be, but Wolpe’s seems tremendously more focused, more taut, more playful, and easier to follow intuitively – if still, at times, mystifying. I’ve always liked the story that Wolpe used to compose while watching fish in his fish tank, making his notes dart, freeze, and scatter as the fish would do. Sometimes he could use abstract hexachords in a way that jumped out and made you notice. Studying piano with a Wolpe student at Oberlin my freshman year (Tom Simon, anyone know his whereabouts?), I was assigned the piano piece Form, and fell in love. That opening little six-note motif – Ab F Bb A G E – returns so playfully as theme, chord, pitch set, riff, tone row, that you really hear it come back in a dozen unexpected guises. Form IV: Broken Sequences is even better, and I love the Trio, the Quartet with saxophone, the Chamber Piece No. 1, the elegant String Quartet, the enchanting Ten Songs from the Hebrew. Such brash, brainy, acerbic music, yet not afraid to be completely obvious at times. I like Enactments for three pianos, too, though without understanding it; I feel like an ant crawling across a late Jackson Pollock mural. I am told that the Mario Davidovsky crowd did not like to hear Wolpe’s name mentioned – he wasn’t systematic enough – and if true, I’m not surprised. He was out of their league.

The Wolpe newsletter’s major offering is a detailed account of the origins of his one Symphony – not one of my favorite Wolpe works, and a little stiff, but the article (without admitting that) explains why: Leonard Bernstein insisted that he greatly simplify the notation, which, originally, was presumably in his usual metrically fluid style. It’s difficult to orchestrate goldfish.

My fondness for Wolpe brings up a point about Bernard Holland’s bittersweet review yesterday of George Perle’s music, whose atonality-bashing will probably earn him another broadside from Counter-Critic (a website that, no longer being a critic, I thoroughly enjoy). I’ve always sympathized with Holland on this issue, yet I disagree with his terminology. Much of Holland’s take is thoroughly common-sensical:

It sounds reasonable to say that Anton Webern’s Piano Variations take up where Brahms left off. I admire the Webern; I even like it for its strangely satisfying space-age spirituality. I don’t think it has anything remotely to do with Brahms.

Touché! On the other hand:

Until the 20th century musicians obeyed natural laws of physics. Pick up a rock, drop it, and it falls to the ground. Music was the same. Send a piece of music up in the air, doctor and twist it, make it major, minor or modal; in the end it wants to come down to where it started. You can call the process tonality or music’s law of gravity.

Of course, almost no composer is going to accede to this. (In fact, psychological studies have shown that musicians couldn’t care less whether a piece comes back to the same key it started in.) Atonality is not the problem. Taking my students as a pristine and unncorrupted audience, there’s loads of wonderful atonal music that they glom onto at first listen, and beg for copies of (Ruggles’s Sun-Treader, most of Varèse, second movement of Berio’s Sinfonia, Stockhausen’s Gruppen, much of Nancarrow, Babbitt’s Philomel, Xenakis’s Pithoprakta, Dallapiccola’s Piccola Musica Notturna, Branca’s Tenth Symphony), and a lot of atonal music that instantly turns them off (Schoenberg’s Fourth Quartet, Webern’s Symphony, Babbitt’s Post-Partitions). Hell, there’s a lot of atonal rock music.Â

As Philomel, Sinfonia, Gruppen, and Piccola Musica Notturna show, even 12-tone organization is not the issue. It strikes me that the deciding factor is whether or not the listener senses that there is some organizational factor that you’re supposed to be hearing that can’t be located by ear, whether the meaning of the piece is buried somewhere underneath the surface. That quality seems to be more what Holland objects to about Perle than the mere lack of tonality. I was dumbfounded by the quotation Alex Ross in his book unearthed from Boulez; asked why the serial pieces of the ’50s never became standard repertoire, the meister admitted, “Perhaps we didn’t pay enough attention to how people listen.” In general, and as evinced by a thousand film scores, atonality tends to express anxiety, and much of the music, like Sun-Treader, that freely acquiesces to that is extremely effective. But Wolpe’s output is Exhibit A that music can be relentlessly atonal and also whimsical, jaunty, and attractive.Â

Our critics need to find a rhetoric in which to discuss the issue that does not make atonality the fall guy. For a splendid counter-example, I highly recommend Justin Davidson’s recent review of Elliott Carter, which elegantly captures, in words I couldn’t better myself, my own disappointed feelings about that composer’s post-1954 music.

Sounding the Solar System

I finished my magnum opus today: The Planets, for flute, oboe, alto sax, bassoon, percussion, synthesizer, viola, and contrabass, commissioned in stages by the wonderful Relache ensemble in Philadelphia. It’s just over 70 minutes long, a 346-page score, in ten movements, my own personal Turangalila. I started writing it in January of 1994, sitting on a plane en route to Seattle next to Laurel Wyckoff, the ensemble’s former flutist. They commissioned the first four movements as part of the Music in Motion project, by which ensembles and composers flew to distant cities to collaborate. The concept was that I would compose every morning and in the afternoons the ensemble would run through what I’d written. I used to be a fairly slow composer, and the plan terrified me. But, under pressure, I wrote the first movement, “Venus,” in a week, and, realizing I could write as fast as someone told me to, I’ve been a fast composer ever since. In fact, I date the coalescence of my mature style from that trip. I was 38.Â

I had always planned to write more movements than the initial four I wrote then, and in 2001 Relache came up with another commission. Their instrumentation was so odd (so difficult to keep that viola audible) that I was reluctant to write a major work for them without assurance that they would play the whole thing, and for years they were in such financial straits that I was afraid to proceed. Also, their instrumentation had changed before, and I feared it might change again before I could finish. But last fall they called and said they were ready to record the work for CD, and told me to get my ass in gear and get those other movements in. So I have, and we start recording next month. Of course, the obvious question is, had my compositional habits so changed over 14 years that the end of the piece would come out very different from the beginning? But I had formed a firm idea back in the ’90s of what each movement would do, and I stuck to my original conception. It’s pretty consistent. “Venus” remains, I think, one of the best movements.

This is my big astrological piece, and of course, there are always people disappointed or horrifed by an admission of any interest in astrology, because most people know next to nothing about it, and have a caricatural view of it associated with newspaper sun-sign columns. I came to the subject via a respectable route. Reading Cage as a teenager interested me in the I Ching and the idea of synchronicity. That led to an interest in several other forms of mysticism, and, eventually, a close devotion to the music of Dane Rudhyar (a far more important and fascinating composer than all but a few of us cult fans will ever admit) led me to embark on reading some of Rudhyar’s 30-odd books on astrology, beginning – as one must – with The Astrology of Personality. Add to that an addiction to the writings of Jung in grad school, and I got caught up in a Jungian conception of the field, based on synchronicity rather than causation. The most important recent writer on the subject is Liz Greene, a brilliant Jungian psychoanalyst.Â

There were other, more personal influences as well. I once worked for an arts organization whose entire staff were clients of the excellent astrologer Doris Hebel. Arts-world interest in the subject is vaster than people talk about. Almost any composer on the New York scene can tell you, if asked, their sun, moon, and rising signs. It’s a social thing. Cage himself was a long-time client of the New York astrologer Julie Winter. I’ve collected music based on astrology, including Holst’s eponymous work (one of my favorite orchestral warhorses), Constant Lambert’s Horoscope, George Crumb’s pieces, and the Interstellar Space recording of John Coltrane, with pieces entitled Mars, Leo, Venus, Jupiter Variation, and Saturn. I took courses in astrology at (apparently defunct) Isis Rising bookstore in Chicago, and, like Holst, I’ve done readings for many a fellow composer. In fact, in 1986 my income as a freelance critic was dwindling, and, having failed (I thought) in that field, I was looking into how to get started as an astrologer when from out of the blue Doug Simmons called me from the Village Voice and offered me a job. (If you know something about astrology, it may interest you to hear that on that very day, Saturn crossed my ascendant and Uranus transited the ruler of my house of employment. Very significant.)Â

I used to fantasize about reviewing concerts astrologically, in advance, like: “Don’t bother attending Nic Collins’s Roulette concert this Friday, Mercury is retrograding over his midheaven, and it’s a sure bet his equipment will malfunction.”

I have to add, too, that with 12 zodiac signs divided into 30 degrees each, with a wealth of experimental aspects like quintiles and septiles calculated within certain degrees of orb, astrology offers a number of delicious parallels with the 12 fluidly-defined pitch areas and continuum of consonances in microtonality. I’ve long savored the feeling of moving smoothly from one to the other without seeming to change the kinds of geometry I’m dealing with. And then, my fascination with rhythmic cycles going out of phase with each other, much manifested in The Planets, was always partly driven by a “music of the spheres” paradigm. Whatever mathematical way my brain is hardwired that drew me to Henry Cowell’s rhythms and Ben Johnston’s scales made me a sucker for astrology as well. Jupiter circles the sun every 12 years and Saturn every 29 years, with a conjunction approximately every 20 years? Now that’s a rhythm, cut me off a piece of that! It’s not all just, “Oh, you’re a Libra, so you have trouble making up your mind.” There’s as much math as you want.

So comments challenging me to defend astrology will be ignored. I never defend astrology, nor proselytize for it, nor say I “believe” in it. I have no idea why astrological transits sometimes seem startlingly relevant, but, like the I Ching, it is an ancient worldview containing a wealth of psychological insight that greatly widened my understanding of human behavior. There are even astrologers who consider it no more than a kind of elaborate Rorschach test, which is certainly one way to understand it. Like anyone who knows anything about the field, I never read newspaper sun-sign columns except for amusement. If you want to bash me for taking an interest in it, go ahead and blast Cage and Coltrane, and feel free to throw me into their camp. I’ll be honored.Â

My mother likes to say, “I don’t believe in astrology; Aquarians never do.”

In any case, as I say in the program notes to the piece, music may not have progressed since Holst wrote his Planets, but astrology has. Rudhyar ushered in an era of “free will” astrology, according to which transits are psychological forces which, if understood, can become channels to new understanding, by which otherwise fated-seeming actions can be avoided. As astrology is now understood as process rather than fate, and minimalism created a new musical paradigm of process-oriented composition, it was time for a new set of Planets to fuse musical processes with planetary ones, rather than the more conventional melodies and atmospheres of Holst’s grand work. I have three more movements than Holst: I include the Sun and Moon, which astrology refers to as “planets,” and also Pluto, which wasn’t discovered until 13 years after Holst finished. (The demotion of Pluto by astronomers has had no effect on astrology.) Each movement follows a process that expresses the idea of its planet. “Sun” is an additive process in the shape of a sunrise. “Moon” is full of melodies and rhythms going out of phase. “Saturn” is a chaconne in which harsh, immobile dissonances are gradually replaced with gorgeous lines of counterpoint. “Uranus” is a jolting collage of constant surprises. The fog of “Neptune” (pictured) has the performers in eight unsynchronized tempos. And so on. John Luther Adams and I agreed that he’ll write music about the earth, and I’ll handle the rest of the solar system.

So after 14 years (half a Saturn cycle), I’ve finally completed the longest instrumental work I have any thought of writing. You can hear the movements that Relache has already performed here. They premiere the entire work in Philadelphia and possibly New York September 26 and 27, by which time we’re hoping to have the CD available as well. It’s a weight off my shoulders. I have dreams of orchestrating the work, but what would I do with a 70-minute orchestral score? Make a nice MIDI realization?

Veni, MIDI, Non Vici

Personally, I don’t mind listening to MIDI versions of pieces not yet performed. I have enough performing and rehearsing experience that I feel I can “hear through” the stiff MIDI limitations and imagine what the piece will actually sound like. It’s an aid, and you have to know how to use the aid and not mistake it for the reality. But I’ve also had enough bad experiences playing MIDI versions for people – people who didn’t seem to possess that ability, and who reacted with a visceral dislike to the piece based on its synthesized version – that I avoid playing MIDI versions for others.Â

Further than that, while it’s one thing to listen to a MIDI file to get a sense of a colleague’s new piece, it strikes me that to listen to a piece that way with the intention of performing it later is an entirely different thing. I’ve had some bad experiences with it. Sibelius (the software) playback has trouble with fermatas, which sometimes get applied to notes they weren’t intended for, and it doesn’t always portray arpeggiated chords or grace notes elegantly; the result being that I have sometimes had to go back and remedially convince the performer that I meant what I wrote in the score, not what he heard on the MIDI file. Of course I could import a Sibelius file into Digitial Performer and sculpt every note, but that’s an awful lot of work for something that isn’t a final product, just a temporary convenience, and the results are still imperfect. Even when such details aren’t a factor, I’m uneasy with the idea that a performer’s first audio experience of a piece will be through a stiffly metronomic version with no nuance. There’s a wonderful process that happens in rehearsal as the players slog through notes whose interrelatedness is still a mystery to them, and then suddenly they hear other parts correctly played in hocket with their own, and everything clicks, and the music emerges from chaos. Then they create the piece from the notation, and it has personality, rather than trying, however unconsciously, to replicate a lousy artifact they heard an mp3 of.Â

But that process takes time, and when an ensemble is short of time, they ask for a MIDI file to speed the process up. As I’ve written here before, “Efficiency in the pursuit of music-making is no virtue.” But I hate to turn down a request from people enthusiastic about playing my music. Perhaps I’m being too sensitive and old-fashioned about it, and this is the way things are done these days, and I’m curious what other composers do and how they feel about it.Â

Those Uptempo Canadians

– Renske Vrolijk’s complete theater work Charlie Charlie, her well-researched and mesmerizingly beautiful postminimalist story of the wreck of the Hindenburg. That was the major Dutch premiere I flew back from London to hear last November. It’s on as I write this, and I can’t stop listening. (Note – if it sounds like the recording is playing on well-worn vinyl, it’s because Renske sampled vinyl noise and plays it in the piece’s background to evoke the milieu. Charming idea.)

– Canadian music, since I’m trying to convince even the Canadians themselves that there’s a lot of good stuff. To that end I’ve put up some pieces by Paul Dolden, whose music is parallel to M.C. Maguire’s in that it hits you with an overload of hundreds of tracks running at once. Just between the two of them, Maguire and Dolden pull the geographic center of North American hair-raising crazy-mad fanatical sonic complexity up to somewhere around Fargo. I also add some major works by that “totalist of Canada” Tim Brady, including his half-hour piece for 20 electric guitars and his Symphony No. 1, which sounds a little like Olivier Messiaen started messiaen’ around with some of Glenn Branca’s MIDI files. That’s pretty high-energy stuff too, so the station’s going through a definite uptempo phase. It must be too cold up in Canada to write the kind of slow, soft, mellow, depressing music a lot of us favor down here. You got to keep even those inner-ear follicles moving.

– Pieces by Jeff Harrington, Ben Harper, Eve Beglarian, some brand new John Luther Adams, Steve Layton, and David Borden, including several installments of his Earth Journeys for Composers (including, so far, For Alvin Curran, For Paul Chihara, and For Kyle Gann). (Hey, it’s another way to get my name on the station.) If you hear some unexpectedly conventional-sounding songs, those are Corey Dargel’s “Condoleezza Rice Songs,” so focus on the lyrics. My concept for Postclassic Radio was always as a way to get my CD collection out on the internet, and I was reluctant to use content that could already be found online, but considering so many good composers don’t have CDs out these days, I’m starting to rethink that a little.

– Some of my recent pieces that premiered lately. Since I never repeat pieces (well, almost never), my own music hadn’t had much of a presence on the station in several months.Â

More to come. Part of the hurdle is always the thought of updating the playlist, so I’ve finally decided to quit trying to make it a guide to the current station, and instead simply list all the pieces I’ve played – which I like to do as a public reminder of the incredible volume and diversity of postclassical music. I finally realized why I’ve suddenly gotten tremendously busy the last few weeks, because next month my three largest non-operatic works are being either performed or recorded. My piano concerto Sunken City needed a few minor revisions prior to its American premiere at Williams College May 9, and I’ve been making a new version of Transcendental Sonnets with a two-piano accompaniment for a May 6 performance at Bard. And I’ve been finishing The Planets, a 70-minute work I started in 1994 and which had laid dormant since 2001. The Relache ensemble is putting it on CD this summer. More of that later, soon, when everything’s finished. Meanwhile, it’ll be safe, and maybe even enlightening, to return to Postclassic Radio.

Downside of Matilda’s Waltzing

your implication that there are orchestral commissions aplenty down here is mistaken. The orchestral scene here is a closed shop, and only members of a certain class get access to it. In my 33 years in Australia, I’ve had access to an orchestra once – and that was when I was a composer in residence with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation in 1987, and I got access to the Adelaide Symphony for 1 day for a recording session. (It’s true I’d never have gotten even that in the US, which is why I say the situation here is better than in the US.) But I’ve never had a commission for an orchestral work here, despite repeated attempts at getting one. My best rejection was when I got a rejection letter that said “please do not send us work of this calibre again.” Felix Werder, currently 85, and still composing (plug: check out the current CD of his electronic music from the 1970s on Pogus) got the same rejection letter for his 7th Symphony, which had just been played in Russia. (The bureaucrat who wrote those letters was later fired, but Felix still hasn’t had an orchestral performance since the mid-90s, when his 1st Symphony (written in an Australian migrant concentration camp in 1942) was premiered.)

The best difference between the Australian and US new music scenes is that Australia has Medicare (socialized medicine) and unemployment benefits without time limit. Those two things make life easier, and less stressful here. That’s why flourishing new music scenes can exist in Melbourne, Brisbane, Sydney, and Adelaide, and Perth.

The main thing to say is that except in Melbourne (where groups such as the Astra Choir, Speak Percussion, and the Melbourne Composers’ League buck the trend), in Australian new music, there is in general a wall of apartheid between music written with notes on paper, and everything else. And composers who work with “everything else” very rarely get a look in, or a chance, to deal with acoustic musicians playing professionally. So we have two (mostly) very distinct scenes here – a scene much like the US, where we make our own instruments, ensembles, improvisers collectives, installations, etc; and a scene of people writing fully notated scores for instruments, which are played by professionals (usually on a charity or pro-bono basis.) There is limited financial support for this stuff (but proportionately more than in the US), and commissions go to both groups (“everybody else”, and “notated for professionals”), and in recent years, when there has been much less funding around, and more competition for it, the funding has been pretty evenly distributed between “everything else” and “notated for professionals.” The funding is not enough (it never is), but it does enable a certain level of activity to keep going.

Nice to have it on such good authority. Nevertheless, when I performed in Brisbane in 2002, I commiserated with Aussie composer Rob Davidson on the problems faced by Downtown music. “Do you know,” he lamented, “that in Brisbane there are only five groups that play this kind of music?” “Rob,” I looked at him incredulously – “that’s how many we have in the entire U.S. of A.” “Oh, I hadn’t thought of that,” he said.

Finding Springtime in a Score

Students are finishing up their orchestra pieces. We’re going through scores and parts with a microscope, making sure every entrance has a dynamic, breaking up undotted half-notes in 6/8 meter, deciding almost arbitrarily whether one oboe or two on a given line, figuring out how far to extend cautionary accidentals, and so on and so on. We’re so petrified that a question about some ambiguity will arise in our allotted 20 minutes of rehearsal. We split hairs to make lines lightning-fast to sightread that aren’t at all difficult to play. It reaches the analogous point of de-italicizing commas in a text document. It’s the most exhausting thing I do during the year.Â

This student’s piece was based on William Blake, and, once finished, we started chatting about Blake. The student had run across a reference to a piece by Eve Beglarian based on Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. I plucked a score of the piece out of my file cabinet, and we opened it. There on the inside cover was a notice from Eve:

EVERYONE: I am definitely interested in hearing suggestions for improvement in the notation & orchestration of the piece. Please tell me of ANY difficulty or confusion or whatever….

[A phone number follows.]

Thanks, and I hope you have fun playing this piece!

What a refreshing jolt back into a less pretentious musical world! Only a woman, or perhaps only Eve, would have the balls to put a disclaimer like that: a note that says not, “I am a professional, I know all, and you must follow my every notated whim,” but, “I am an artist and I’m trying something no one’s ever done before, if it doesn’t work out for you give me some feedback.” What a dreary mausoleum the orchestra is. What a breath of fresh air Eve is.