It’s pretty far down in the comments now, so I didn’t want it to get lost that Wiley Hitchcock’s son Hugh has started a remarkably honest blog about his late father, with a standing invitation for people to post their memories of him there.

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

It’s pretty far down in the comments now, so I didn’t want it to get lost that Wiley Hitchcock’s son Hugh has started a remarkably honest blog about his late father, with a standing invitation for people to post their memories of him there.

I finally got a recording of my piano concerto Sunken City – by recording it off of Dutch radio via the internet:

First movement: Before (7:43)

Second movement: After (22:19)

The recording is of the premiere in Rotterdam, which had a few more mistakes than the next evening’s concert in Amsterdam, but the spirit of it is quite nice. The ensemble is the Orkest de Volharding, the crackerjack wind and brass ensemble founded by Louis Andriessen in 1972, conducted by the young but impressively expert Finnish conductor Jussi Jaatinen. The soloist is Geoffrey Douglas Madge, an Australian pianist living in Amsterdam since the ’70s. Few I talk to in the U.S. have heard of him, but he long ago recorded the complete Busoni piano music for Philips, and gave the Chicago premiere of Sorabji’s massive Opus Clavicembalisticum in the mid-’80s, so he’s been a big figure on my radar screen for a couple of decades. It was a great honor to have worked with him, and I found him a kindred spirit and a convivial conversationalist. Here’s a photo of him rehearsing just before the premiere (the other half of the ensemble is outside the picture frame):

Of course, I got blasted in the local Amsterdam Picayune by the same critic whom all the Dutch composers hate because he’s blasted them as well. The only stated complaint was that the piece was too long, which is the most superficial kind of comment; I have tried, throughout my critical career, to avoid ever simply calling a piece too long, because that doesn’t mean anything. If Tristan isn’t “too long” at four hours, how can anything shorter be “too long”? What a decent critic would say instead is something about the structure of the piece that makes the overall form unwieldy. Typically such a work will be unclearly articulated, with too much sectional variety to grasp as a large structure. But in this case, the long second movement is a simple alternation of tutti sections and piano solos, ABABA in that respect after a short introduction of piano chords. It is also a chaconne, one of the simplest of forms, interrupted by a jazz section quoting Jelly Roll Morton’s “Dead Man’s Blues,” and returning at the end to the opening chords in a freer order. The chaconne does contain 17 chords, because I needed at the beginning to suggest the seeming eternity of New Orleans victims waiting for help. I have my qualms about the work’s orchestration, transitions, and other details, but there is nothing about it I am more certain about than that it is not too long. (While composing I even found the piece getting too large and compressed some sections.) And no composer in the world knows better than I do exactly what such reviews are worth.

Much more to the point, probably, is that the second movement is rather sad and Romantic, and as one experienced Amsterdammer warned me, “The Dutch critics don’t like sentimentality.” The piece is, I’ll remind you, an homage to and memorial for New Orleans. I’ve already blogged the program notes, so won’t repeat them here. You can download a PDF score here if you want.

I have a didactic point to make about the performance. You will notice that some of the solos are rather jazzed up, with tasteful pitch bends. I did not notate these. They are, generally speaking, exactly what I wanted. The Volharding players, being smart and sensitive musicians, inferred from the nature of the music precisely what would sound appropriate and played it creatively and in the right spirit. I didn’t coach them on that at all – they were already playing it that way when I arrived. So much for the Midtown fallacy that every nuance has to be exactly notated or no one will know how to play your music. Many Pulitzer- and Grauwemeyer-winning composers would say that my score to Sunken City is “undermarked,” and thus “unprofessional” – and yet a European ensemble, who had never heard my music before, divined exactly the degree of looseness that would make me happy, and achieved it with no input from me. How is that possible? Surely I can’t be right in what I’ve been saying for twenty years, that if you write music clearly enough you can trust smart, sensitive performers to play beyond the notation to find the right feel for the music? Or does this performance, perhaps, prove the orchestral hotshots’ mandate about notational exactitude to be the ideological horseshit it’s always been?

With that in mind, enjoy.

UPDATE: Friend John Luther Adams provides a comforting thought: “Your piece isn’t too long. That critic is too short.”

Peter Cherches has written, for NYU’s Fales library, a research guide to Downtown music, concentrating on the years 1971-1987. I started at the Village Voice in 1986, so this is yet more confirmation that the Downtown scene existed and was well recognized as such long before I came along and started writing about it. In order to get more data from readers, he’s also started a blog on the subject. At the Voice I covered the “classical,” more new-music side of the scene, but Cherches covers the jazz and punk rock areas as well. Got a problem with Downtown music? Take it up with Peter Cherches now. Go tell him there’s no such thing.

I was in Washington, D.C., this week lecturing at Catholic University, and I spent a number of fruitful hours at the impressive National Museum of the American Indian. Among other things, I bought a book on Cherokee astrology: The Cherokee Sacred Calendar by Raven Hail, an elder in the tribe. It seems that Cherokee astrology – apparently based on or descended from the Mayan system, which I wasn’t familiar with – is based on a 260-day Venus cycle. Venus is the morning star for 260 days, then it’s the evening star for 260 days. This 260-day period is divided into 13 periods of 20 signs and 20 periods of 13 numbers. The signs of the Cherokee zodiac are:

Turtle

Whirlwind

Hearth

Dragon

Serpent

Twins

Deer

Rabbit

The River

Wolf

Raccoon

Rattlesnake Tooth

Reed

Panther

Eagle

Owl

Heron

Flint

Redbird

Flower

These signs run by, one a day, sunrise-to-sunrise, in a 20-day cycle. Meanwhile, the 13 numbers go by in a concurrent 13-day cycle.

For instance (and you need to look at the book’s appended ephemeris to find out where your birthday fits in), I’m a Wolf and a 6. The Wolf, according to Hail, is “a two-way personality – genial to his own kind, but savagely protective against all outsiders. Lover of freedom and the wide open spaces. A ‘don’t fence me in’ character. The paradox here is that he marks his own territory aggressively, fencing others out!” And as a 6, I’m “an incurable romantic, in pursuit of the true, the good, and the beautiful.” Fair enough.

Let’s try Stockhausen, since he’s on everyone’s mind. Assuming he was born after sunrise, he’s a Flint and a 12. Flint is “a creator, an originator, an innovator. Opener of The Way to new pathways. He has a keen mind and a lively curiosity to explore beyond the confines of the status quo…. He inspires mental expansion in others, and stretches the mind to the outside limits of any capability in physical and spiritual development. He changes the static to the dynamic.” A 12 is one who “spiritually turns on the light, turns up the heat, and starts the motor running.”

OK, pretty cute. But if you know how I think, and know what kinds of things I like to write about here, you can anticipate what intrigues me about this. It’s that idea of conceptualizing time as cycles out of phase with each other, so that a series of 20-day “months” and 13-day “weeks” are interacting and influencing each other as they go by. And on top of that, the 260-day Venus cycle encompassing them is off kilter with the more obvious 365-day sun cycle and 28-day moon cycle. It’s a more strictly numerological system than European astrology, because it reduces to 13 x 20 even though the Venus cycle isn’t exactly 260 days, because there’s a regular daily progression, and there are no retrograde planets. I love thinking of the Cherokees or Mayans having kept track of the passing of time via these overlapping, out-of-sync rhythmic cycles. And since family legend has it that my great-great-grandmother was a Cherokee, I almost wonder if my love of these cycles is sparked by some ancestral memory stored in a bit of DNA. (The story is that my great-great grandfather married a Cherokee woman, and his siblings were so horrified that they came from Arkansas to Oklahoma and kidnapped my great-grandfather so he wouldn’t be raised by an Indian. Family lore, can’t confirm any of it. And my mother’s father was supposed to have been a bank robber in Louisiana, or so Grandmother said.)

If I had run across this information 20 years ago, I’m sure I’d have at least one Cherokee-inspired piece of music based on the 20 x 13 grid by now. I no longer compose so strictly, but I’ll keep the idea in mind.

….In February 1913, Malevich assured Matiushin that “the only meaningful direction for painting was Cubo-Futurism.” In 1922 the Dadaists celebrated the end of all art except the Maschine-kunst of Tatlin, and that same year the artists of Moscow declared that easel painting as such, abstract or figurative, belonged to an historically superceded society. “True art like true life takes a single road,” Piet Mondrian wrote in 1937. Mondrian saw himself as on that road in life as in art, in life because in art. And he believed that other artists were leading false lives if the art they made was on a false path. Clement Greenberg, in an essay he characterized as “an historical apology for abstract art” – “Toward a Newer Laocoön” – insisted that “the imperative [to make abstract art] comes from history” and that the artist is held “in a vise from which at the present moment he can escape only by surrendering his ambition and returning to a stale past.” In 1940, when this was published, the only “true road” for art was abstraction. This was true even for modernists who, though modernist, were not fully abstractionists: “So inexorable was the logic of the development that in the end their work constituted but another step towards abstract art….”

To claim that art has come to an end means that criticism of this sort is no longer licit. No art is any longer historically mandated as against any other art. Nothing is more true as art than anything else, nothing especially more historically false than anything else. So at the very least the belief that art has come to an end entails the kind of critic one cannot be, if one is going to be a critic at all: there can now be no historically mandated form of art, everything else falling outside the pale….

– Arthur C. Danto, After the End of Art, pp. 27-28

And again:

Contemporary art… has no brief against the art of the past, no sense that the past is something from which liberation must be won, no sense even that it is at all different as art from modern art generally. It is part of what defines contemporary art that the art of the past is available for such use as artists care to give it. What is not available to them is the spirit in which the art was made. [Emphasis added in both cases.]

– ibid., p. 5

Arthur Danto is an excellent philosopher of art whose work has sometimes inspired me creatively. What he means by “the end of art,” I should clarify, which event he dates roughly to the 1970s, is not the cessation of meaningful artistic creation, but the end of a monolithic cultural conception of art that grew in the early 15th century. And I take pleasure in reiterating his most concise conclusion: No art is any longer historically mandated as against any other art. “There can now be no historically mandated form of art.” Not everyone knows it yet – but we have indeed turned a corner.

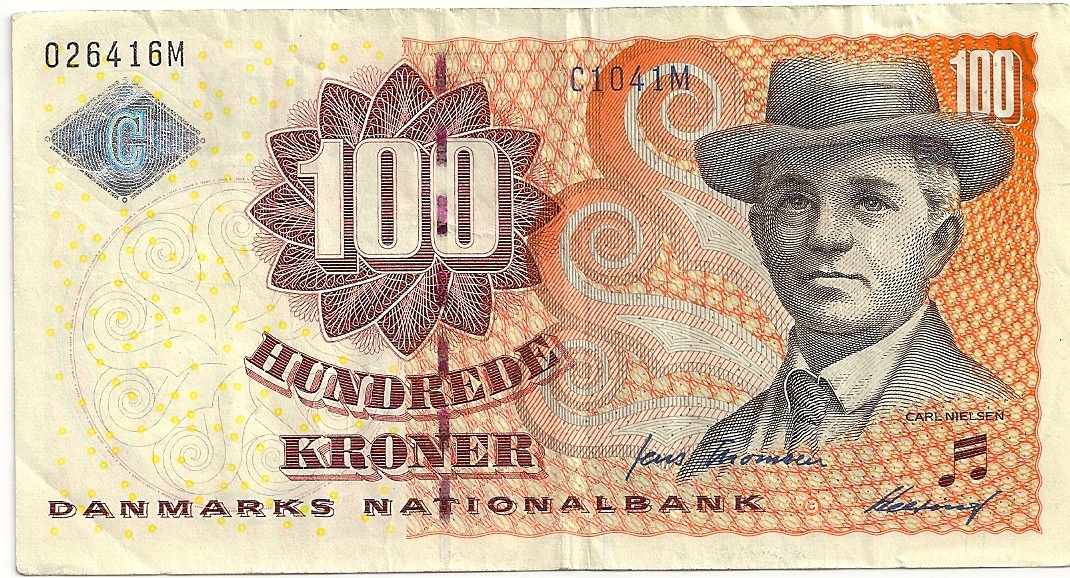

Europeans certainly do make a composer feel at home. No sooner had I stepped off the plane in Copenhagen than the Bureau d’Exchange handed me several pictures of Carl Nielsen:

In Basel I turned in my Danish Kronens for pictures of Arthur Honegger:

And the Swiss went the Danes one better: not only was their most famous composer on the front, but the reverse of the Swiss Franc sported an actual excerpt (a mere repeated dyad, admittedly, but all the more characteristic withal) from Pacific 231 (detail only):

Somewhere around here I have an old, pre-Euro, five-Franc note bearing a likeness of Claude Debussy, but I elected not to bring home the soon-to-be-extinct British twenty-pound note with a drawing of Sir Edward Elgar. The exchange rate being what it is, $46 USD seemed a little dear for the author of Pomp and Circumstance.

I’m out of town on a teaching gig, which is perhaps why the news eluded me that my friend and mentor Wiley Hitchcock passed away Wednesday. It seems terribly unfair that death could ever be associated with such a big, bluff, jovial, good-natured, generous, straight-shooting bear of a guy, as jaunty, masculine, and bullshit-deflecting as a sea captain. He was the dean of Americanist musicologists, and far more than a musicologist – he seemed a full-fledged denizen of the world of American composers, someone who walked among Ives, Thomson, Cowell as a friend and equal, clarifying what they meant and finishing up their business for them. Wiley (what a perfect name for him, more to do with the coyote than with anything “wily”) and I used to have lunch in Manhattan together about once a year, and he’d tell me about all the work he was doing on the score to Four Saints in Three Acts, or in getting together the new edition of every last Ives song. He gave you the feeling that musicology was a real “man’s game,” not for the faint at heart. Then he came down with cancer of the larynx a couple of years ago and our last lunch got postponed, with recurring promises that it would happen eventually – but it never did.

There is no one to whom I am more professionally indebted. He wrote me countless recommendations, badgered professors to hire me and publishers to consider my book proposals, and allowed me to write the post-1980 chapter of the fourth edition of his classic textbook Music in the United States (which, with his usual self-effacing humor, he invariably referred to by its near-acronym MinUS). He treated me like a favorite nephew (or so it felt), and I worshipped him like an uncle known for glorious exploits.

I have to record the one influence I can say I had on Wiley. Once we had lunch at the seafood restaurant (we always had seafood) at Grand Central Station. He broke it to me that he wasn’t going to put out a fourth edition of MinUS. Nobody seemed interested in ordinary music history anymore, he said, everyone was doing “reception history,” and feminist history, and deconstructionism, and there wasn’t any room anymore for someone to simply record events. “But Wiley,” I responded, “just because people are getting interested in all these different ways of doing history doesn’t mean that traditional history will come to an end. Someone still needs to write down the basic record of what composers wrote and when.” He grew thoughtful, and within a few months I got word that MinUS was back on track. What I wouldn’t give for another one of those expansive lunches with their wide-ranging conversations through the world of American music.

UPDATE: Stockhausen has died, too.

UPDATE: And Andrew Imbrie and Cecil Payne and Carlos Valdés and András Szöllösy.