Thousands of people consider Elliott Carter a great composer. He’s won two Pulitzer Prizes, and gets performances and even retrospectives out the wazoo. He is assured his chances with posterity, regardless of what I do, or what any other individual does. Aside from the royalties he’s missed by my not buying all of his recordings, twenty years of my expressing misgivings about Carter’s music has not caused five dollars’ worth of harm to his finances or his career. If I really thought any of my ideas could truly do harm to Carter, I would be more reticent about expressing them. I have nothing personal against the man. In the case of far less well-known composers, however, it is possible that a negative review from me might do real damage.

This is why, as a Village Voice critic, I always maintained an ethical policy of only writing negative reviews in cases in which the support given the composer (or performers) was sufficiently compensatory. I have a vague idea that this reflected Voice policy in general, though I can’t specify how I was aware of that. For instance, if Lincoln Center or BAM presented a concert, all gloves came off. Large-scale institutional support for a composer, together with the attendant publicity machine, requires objective criticism as a counterweight. (As Virgil Thomson said, music criticism “is the only antidote we have to paid publicity.â€) Many voices would weigh in in such a case, and it was incumbent on each of us to register our opinion as to whether the composer involved merited such grandiose support. The smaller the venue, the less incentive there was to review a composer who failed to impress me. If I heard a concert I didn’t like at Roulette, or the Performing Garage, or some other small space, I would usually simply not review it. There was no reason I could see to draw only negative attention to an artist who, otherwise, would have received no attention at all.

There were exceptions. Sometimes one artist I didn’t care for would perform on a concert otherwise well worth reviewing. In a couple of cases, artists pestered me so urgently for a review that I had to take them at their word and assume that they would prefer honest disapproval to no public reaction at all. Occasionally I would attend a concert I had expected to like, be very disappointed, and not have time to find another concert before my next column was due – thus the negative review appeared perforce. In general, though, I tried to avoid giving negative reviews to artists who were having a hard time making it and getting very little institutional support; if I couldn’t find anything redeeming to say about their work, I would simply ignore them. I would, however, review artists whose work I didn’t like if they were famous and/or getting programmed at major venues. For one thing, my conscience was always clearer if I wasn’t the only critic commenting. Of course, at the Voice I had a luxury few publications provide, of being able to pick and choose what concerts I wanted to write about.

All this is to explain why I am going to impose on the comments that come in response to this blog the same policy I applied to my career. Most of the composers I write about here are not regularly written about by anyone else. Their music is not well-known even among the rarefied circles of new-music connoisseurs. Some of them have little keeping them in the public eye beyond my enthusiasm and that of their immediate colleagues. My advocacy alone is in little danger of bringing them to an undeserved level of worldly success. All of them have in common that I find their music important or interesting in some way or other, even if the musical examples I cite may sometimes be chosen more to illustrate a technical point rather than to prove their attractiveness. I would be ill serving these composers if, in my advocacy, I peripherally left their music open to harsh criticism by every malcontent who chooses to read my blog. Nor should they be held to account for the way I present their work – they themselves might present it quite differently. If I’m just demonstrating technical features, then whether you like the music or not is truly neither here nor there.

If I provide a musical example that you don’t like, you are perfectly free to express your opinion of it on your own blog, at some other forum, or at any other web site. I will not, however, publish that negative opinion here. Most of the negative opinions of music by my peers that I’ve expressed during my career were elicited by the incentive of money, because criticism was my livelihood. My reputation as a dependable critic required the trust of my readership, which demanded honesty on my part, entailing the occasional negative review. Few who respond to my blog have similar incentives. If for some reason you are particularly desirous that I become aware of your unfavorable reaction to music I post here, feel free to drop me an e-mail. But I will not subject the composers I champion to the sting of harsh comments by the random public of internet passers-by. Besides, I submit that it is rather stupid to sign your name to a public, Google-able, harsh disparagement of the music of a total stranger without having any professional reason to do so. In that sense, I am protecting you from your own baser impulses.

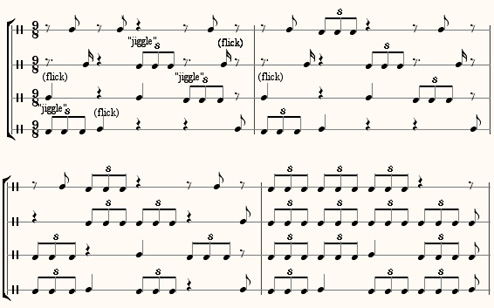

As for the objections that were voiced concerning Mikel Rouse’s Quick Thrust, most of them had to do with the allegedly stiff nature of the drum playing. I simply do not acknowledge this as a deficit. For one thing, the piece dates from 1984, at the very beginning of the classical attempt to incorporate rock materials into a classical structure, and indeed, at the very beginning of Mikel’s career. More generally, new music has been largely an attempt to arrive at a music in between classical music and pop music. This compromise has met with violent resistance on both sides: from the classical musicians who refuse to take music with pop elements seriously, and from the pop fans who refuse to countenance music that uses drum sets but is played from a score, and played faithfully to the notation. Believe me, over a 23-year career as a critic, I have received a couple of billion messages to indicate that most musicians hate the music I advocate for one reason or the other. Most musicians never wanted an in-between music, only more of what they already had, and they will never, ever give the in-betweeners any credit for trying. Many pop fans are especially dogmatic in their unalterable position that a piece that uses trap set MUST HAVE THE LOOSE, DYNAMIC ENERGY OF ROCK or the heavens must fall. For all that Mikel has come a long way since 1984, I, as a classically-trained and -raised musician, prefer the tight drumming-to-structure relationship in Quick Thrust to more typical rock drumming. You do not. Your opinion is noted, once again. Clearly, this music is not for you. I recommend not listening to it. That does not mean, however indignant you are in your opposition and however ardently you feel otherwise, that it is bad music. It simply doesn’t.

The most frequent and bitter complaint I’ve gotten about my book on Nancarrow over the years has been about the price. But I’ve just learned – over the

The most frequent and bitter complaint I’ve gotten about my book on Nancarrow over the years has been about the price. But I’ve just learned – over the

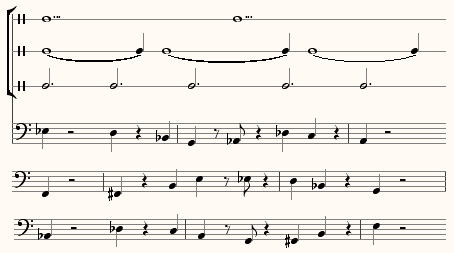

I had never heard Mosko’s music, but was well aware of his activities as a conductor. I once reviewed his Newport Classic recording of Feldman’s For Samuel Beckett as being the best available. Last week Art Jarvinen was kind enough to send me the O.O. Discs CD of Mosko’s music, performed by the California Ear Unit, and he tells me there’s a hard-to-find one on Cambria as well. I had no idea what to expect. Mosko’s music is thorny – or gnarly, in the parlance of our time – but his time sense is distinctive. Even when the music’s individual gestures are quick, it sustains its focus for many moments in succession, and changes slowly. It is quasi-atonal in a way that allows tonal passages to happen in a non-quotation-like way, almost as if it simply makes no distinctions among sonorities. Therefore it is playful rather than tense, with highly soloistic instrumental writing, and reminds me, more than anyone else, of Stefan Wolpe’s music. There is much stasis, dotted by delicate bursts of activity that build up no momentum. His early influences include Webern, Feldman, Cage, Icelandic folk music, and Sufi music, the first three more evident than the others.

I had never heard Mosko’s music, but was well aware of his activities as a conductor. I once reviewed his Newport Classic recording of Feldman’s For Samuel Beckett as being the best available. Last week Art Jarvinen was kind enough to send me the O.O. Discs CD of Mosko’s music, performed by the California Ear Unit, and he tells me there’s a hard-to-find one on Cambria as well. I had no idea what to expect. Mosko’s music is thorny – or gnarly, in the parlance of our time – but his time sense is distinctive. Even when the music’s individual gestures are quick, it sustains its focus for many moments in succession, and changes slowly. It is quasi-atonal in a way that allows tonal passages to happen in a non-quotation-like way, almost as if it simply makes no distinctions among sonorities. Therefore it is playful rather than tense, with highly soloistic instrumental writing, and reminds me, more than anyone else, of Stefan Wolpe’s music. There is much stasis, dotted by delicate bursts of activity that build up no momentum. His early influences include Webern, Feldman, Cage, Icelandic folk music, and Sufi music, the first three more evident than the others.