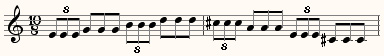

During Bard’s Janacek festival a couple of years ago, I became rather impressed with that composer’s textural and tonal originality, especially upon realizing that I had always thought of him as a 20th-century composer and he was actually born in 1854. So awhile later, browsing at Patelson’s in New York, I ran across the sheet music to Janacek’s On an Overgrown Path – the piece that the well-known eponymous blog is named for, I suppose – and picked it up. It sat on my piano for months, but since I moved to a new house, my Steinway has developed a terrible case of sticking notes, rendering it unsatisfying to play, and piano tuner time is at a dear premium up here. So at an odd moment I finally decided to listen to the new ECM recording of the piece with András Schiff while following the score. It’s a lovely recording – except that Schiff can’t handle the 5/8 meters that come up in a couple of movements. He plays this passage:

by speeding up the first three 8th-notes notes and prolonging the last two (even extending the left-hand D-flat into a quarter-note), turning the meter into a more conventional 6/8, as you can hear here, and disappointingly taking the edge off of Janacek’s rhythmic originality. (In fact, when the music reverts to 2/4 in the 5th measure, Schiff’s 8th-note suddenly slows down by 50 percent, making it clear that he was feeling the 5/8 as 2/4 with triplets all along.)

This wouldn’t merit mentioning if it weren’t so common. Classical musicians are taught early in life that a measure is a rhythmic unit, divided into two or three parts, and if divided into more, then divded according to a symmetrical heirarchy: 2 groups of 2, 2 groups of 3, 3 groups of 3, and so on – or not and so on, because that’s about it. Of course, quite early in the 20th century – On an Overgrown Path is a hundred years old – composers opened up a new conception of meter, as a quantity of equal or even unequal units. Musicians accustomed to playing composers as long-dead as Stravinsky and Copland are used to negotiating 5/8 and 7/8 meter, but it’s surprising how many professional musicians have never added the new paradigm to their repertoire. They recognize it and think they know how to do it, but when they start to play, their body-need for a regular beat, like Schiff’s, overrules their visual cognition. I have to warn my students, some of whom gravitate to 13/16 and similar meters under the influence of notation-software-induced ease, that some classical players will have to be taught how to play the rhythm, and that they might not be teachable. Recently a student wrote a passage in 10/8 meter, with the following quite elegant rhythm that required four beats per measure, quarter-notes on 1 and 3 and dotted quarters on 2 and 4:

It seemed perfectly simple to him and me, but the performance, by professional players steeped in 19th-century music, was a disaster. They ended up speeding the non-triplet 8th-notes into triplets, and making it a kind of bumpy 4/4. No amount of pleading could get them to feel successive beats as unequal.

I face the same mentality when I show people my Desert Sonata for piano, which has a long moto perpetuo passage in 41/16 meter. Certain people look at it and exclaim, incredulously, “How do you COUNT that?!” Well, of course, you don’t count it, but if you will play the 16th-notes evenly and in the order indicated, I promise it will come out all right. What they want, of course, is some heirarchical division of 41 that they can funnel all those 16th-notes into, and there just isn’t one. (Please don’t be tiresome and advise me to renotate it in 4/4 – the 41/16 clarifies the underlying isorhythm, and mangling it into 4/4 would turn it into an unmemorizable mishmash.) By now this new metric paradigm is very common among young composers – Sibelius notation software will handle meters up to 99/32 just as easily as 4/4 – and so it’s astonishing to still find it so missing in classical music pedagogy. In 1947 Nancarrow turned to the player piano because the musicians he met couldn’t play the comparatively simple cross-rhythms he was writing. Were he to come back today, there are circles in which he would find that things haven’t improved much.

their star pianist Sarah Cahill (pictured) will play a piece of mine, “Saintly” from my Private Dances, along with works by others from the still-kicking set like John Adams, Terry Riley, and Mamoru Fujieda. There will also be some works for Disklavier presented, including a new work by Daniel David Feinsmith, my own Nude Rolling Down an Escalator, and a couple of Nancarrow’s Player Piano Studies. Sounds like one of those great San Francisco new-music marathons, with Cahill featured throughout (both my pieces are on the 5:30 concert). Wish I could say I’ll see you there, but I’ll be in upstate New York, kicking myself for not having moved to California right out of college like I was tempted to.

their star pianist Sarah Cahill (pictured) will play a piece of mine, “Saintly” from my Private Dances, along with works by others from the still-kicking set like John Adams, Terry Riley, and Mamoru Fujieda. There will also be some works for Disklavier presented, including a new work by Daniel David Feinsmith, my own Nude Rolling Down an Escalator, and a couple of Nancarrow’s Player Piano Studies. Sounds like one of those great San Francisco new-music marathons, with Cahill featured throughout (both my pieces are on the 5:30 concert). Wish I could say I’ll see you there, but I’ll be in upstate New York, kicking myself for not having moved to California right out of college like I was tempted to.