The album Eno Piano will be released by InFiné on November 10, 2023. Additional tracks will be released in 2024.

My new album got started with a question: Is it possible to play Music for Airports on the piano? Brian Eno’s original studio recording contains a lot of piano sounds, but they are manipulated, redistributed, dehumanized, or rehumanized. And then there are long, long sustained tones. The gorgeous defining long notes! (Some of them are vocals.) How to do that with a piano? Acoustic piano sounds decay, immediately, unstoppably. The piano is a big decrescendo machine.

In my recording of William Duckworth’s The Time Curve Preludes, I used the prescribed metal weights to hold down some keys on the piano keyboard. That allows continuing resonance and vibration for the selected pitches. But that’s a rather subtle change, a prolongation of the inevitable fade-out that’s part of a note played on the piano. The piano does have its great secret weapon, the right pedal, the pedal that raises the dampers on each string. Most of the time, we just call it “the pedal.” Called by Ferruccio Busoni, “a photograph of the sky,” it can be overused, certainly. Yet, the nuances of pedal use remain under-explored. The virtuosic pedalist can lighten the resonance of an already sounding midrange tone while preserving a bass line, or modify the sound of a single note after it is played…

I heard the fine jazz pianist Evan Allen (who was my student for a time) using an eBow inside the piano. (The eBow is a device used on the electric guitar to vibrate a string, producing a long, sustained tone.) Evan managed to fit an eBow to a piano string and make a drone. Around the same time, I mentioned all of this to Alexandre Cazac, the far-sighted director of InFiné, the French record label with which I make albums. Alexandre told me about an inventor in France who was making electro-magnetic “bows” designed to make piano strings vibrate. In some online meetings, during the global pandemic, Florent Colautti demonstrated and described his bows. They seemed perfect for making the long sounds in Music for Airports.

Suspended over the piano strings, the electro-magnetic bows can be turned on directly. They can make a piano string produce its fundamental pitch, or overtones, or more complex and colorful vibrations. In recording Eno Piano, sometimes the bows were responding to a piano track played back through the bows — that is, somewhat ambiguous electronic signals were turning the bows on and off…

The composer Simon Hanes helped me tremendously by transcribing Music for Airports into notation on paper! (Eno’s music existed as sounds made in the studio but not written.) Later, I added further details to the scores and specified more time elements in the notation. I also transcribed four additional short pieces that were eventually recorded along with Airports.

Eno Piano is not just the title of an album. It represents an aspiration: the use of new technology and new techniques to make an instrument, a transformed piano, an “Eno-piano”! With the collaboration of Alexandre Cazac, Florent Colautti with his electro-magnetic bows, the highly expert engineer Martin Antiphon, and me, we produced the recording only using sounds made by an acoustic piano — and yet including some sounds never heard before.

It concerns me that today’s extremely high level of classical piano virtuosity has little impact on the world. Already in the 1970s Roland Barthes wrote: “For today’s virtuoso, much esteem but no fervor.” It becomes more true every year. The resource of musical virtuosity that exists in the world today is used narrowly, focused on a very small amount of music by a tiny number of dead composers.

Eno Piano is a piano album; at the same time, it is a blending of old and new — and a blending of two musical worlds, two societies, the “classical” and the “electronic.” In post-production, engineer Martin Antiphon used Ircam SPAT to spatialize sounds and add movement. Some slight detuning was introduced, and some simulation of the texture of sound recordings made on magnetic tape.

Brian Eno famously said, “The studio is a musical instrument,” I am now saying that a musical instrument (the piano), can be a studio! I’m using acoustic sounds made with a piano to recreate or reinhabit the music Eno made using the resources of the studio.

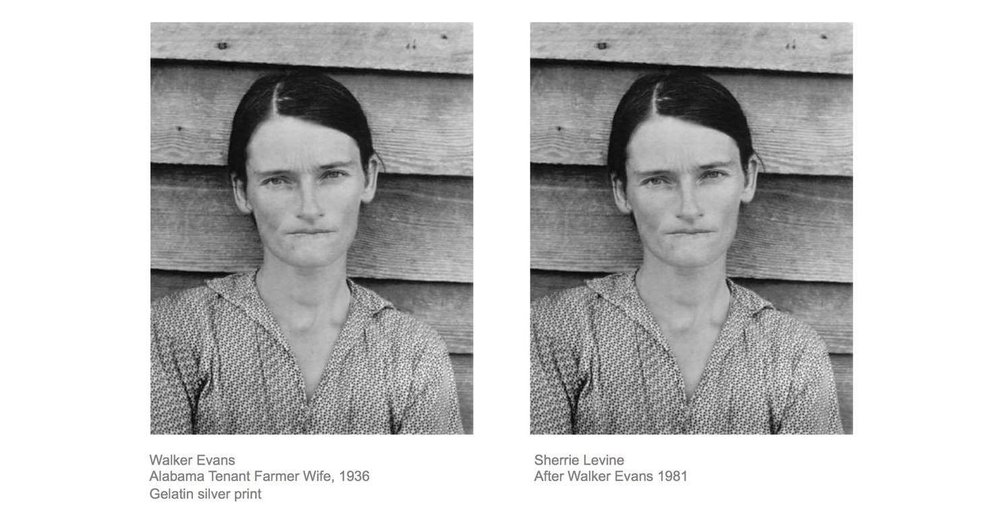

Artists who rework, repurpose, and otherwise reuse older art fascinate me. Sherrie Levine photographing photographs by Walker Evans, the band Mostly Other People Do The Killing making the sounds of Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue, Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music played live by Zeitkratzer.

As I think about Brian Eno’s use of piano sounds in his studio-made recordings, it crosses my mind: Am I imitating something that was an imitation to begin with?

During work on Eno Piano, a deck of cards printed with Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt’s “Oblique Strategies” was in the studio. Sometimes, these answers to artistic questions guided the creative process. Most significantly: “Repetition is a form of change.”