Dispatched from the Audition Room

(mit Bolzano auch dabei)

After the third day of piano auditions at New England Conservatory, I attended an evening recital given at the school by one of my piano faculty colleagues. Backstage, he said that while he was playing he imagined my stern voice from the audition room. Making a fairly unpleasant face, he told me, “You know when you say, ‘Mmmmm, not really good…‘”

The cold fact is that from about 450 applicants in classical piano, we are going to admit no more than 25 new students this year. Many more musicians are applying than in the past. The overall quality of playing has improved a lot. We are certain to reject some players who more than meet the level of students who were accepted in earlier years.

Many different interconnected decisions and choices are taking place during the auditions. By the end of several long days during February we will winnow our long list of pianists, of course. We will also gain insights into many other schools, other teachers, how music is being made in the world, and significantly — insights into ourselves.

Many different interconnected decisions and choices are taking place during the auditions. By the end of several long days during February we will winnow our long list of pianists, of course. We will also gain insights into many other schools, other teachers, how music is being made in the world, and significantly — insights into ourselves.

Indeed, as we judge these prospective students, we judge ourselves.

The pianists assembled to hear the auditions are not unified in our musical outlook, beliefs, or opinions. A student accepted at the conservatory will receive weekly one-on-one lessons in which their assigned teacher may demonstrate playing — or eschew demonstrating. Is the teacher giving specific instruction on the performance of particular music, or something else?

Some years ago at Juilliard, Jerry Lowenthal said somewhat whimsically, “The trouble is the faculty is envious of the students.”

Sometimes I have been goaded to be more perceptive, more useful in my teaching — by students whose exceptional capacities have jolted me into heightened awareness and resourceful experiment.

Consider the situation of coaches who work with Olympic athletes. Those kids are swimming faster, jumping higher, achieving verifiably better results than previous generations. There is no question the sporting achievements of the coaches are surpassed by those they train.

Whenever we seek instruction or advice we may consider the help we get from someone who has done the thing we are attempting or gone through the situation we face. Then there is the useful advice that can come from someone who has not done our task, or even worked in our field. Teachers of elite musicians are often serving in both ways. We have surmounted some of the challenges faced by our students. But these young artists may take on repertory we don’t know, find new paths, go in new directions. The context for their work is going to continue changing.

As we hear youngsters vividly perform the “standards” of our own performing repertory we may search for ways to hold on to our identity. We might favor prospective students who are already close to our artistic viewpoint, or technical inclinations. We may overestimate our own musical sensitivity or emotional connection to music.

I say to colleagues that our personal artistic opinions are not as important in considering prospective students as our expert evaluation of their potential. It may be quite difficult to make such a distinction.

By giving a high rating to a student who plays with significant memory slips or technical breakdowns we might be expressing our hope that these faults don’t matter too much — in our own performances. By reflecting in our ratings, our discernment of fine gradations of technical accomplishment we might be showing off how perceptively we hear. John Cage tells us, “The most that can be accomplished by no matter what musical idea is to show how intelligent the composer was who had it … the most that can be accomplished by the musical expression of feeling is to show how emotional the composer was who had it.”

Excellent musicians are not necessarily perceptive listeners to others. What if our piano auditions were evaluated by a team of pop recording producers with their highly refined hearing? But, that might focus too much attention on surface or product, and not consider artistic process sufficiently…

Some of the prospective students we hear are very advanced — ready to play concerts now — and offering, in their audition programs, “difficult” music. We have heard several performances of Beethoven’s “Hammerklavier” Sonata, Brahms’s Opus 1, numerous performances of Ravel’s “Ondine” and “Scarbo,” and many performances of Chopin’s Fourth Ballade and Fourth Scherzo, now commonplace among ambitious high-schoolers.

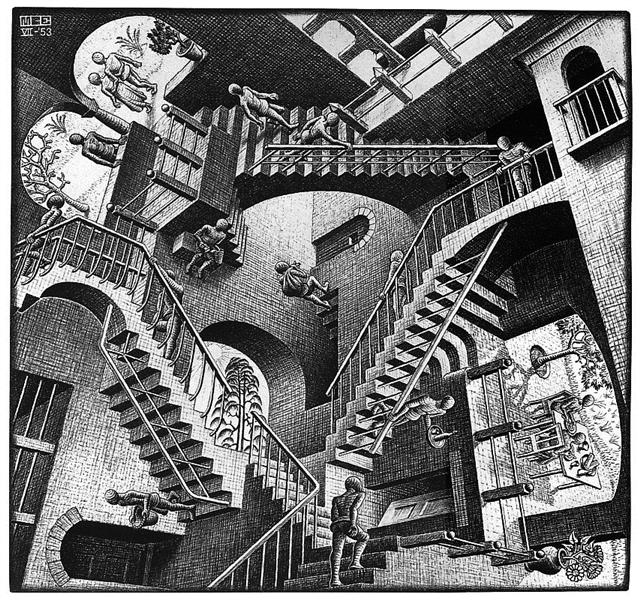

The gatekeeper in a medieval city was important. He protected the city, controlling the traffic — yet in order for work and life to continue, he let some people in.

unbelievably perceptive. thank you for this!