The character of a piece of music is strongly influenced (or sometimes distorted) by the technique necessary to play it. The physical motions of fingers and arm will color the music being made. There is always an interaction between a musical idea (perhaps written) and the movements of a human body that are necessary to realize the idea in sound.

The character of a piece of music is strongly influenced (or sometimes distorted) by the technique necessary to play it. The physical motions of fingers and arm will color the music being made. There is always an interaction between a musical idea (perhaps written) and the movements of a human body that are necessary to realize the idea in sound.

Delicate or fragile music that requires advanced virtuosity is especially challenging. As is any difficult-to-play music that’s humorous or comic.

The virtuosic first-movement of Beethoven’s Opus 7 Sonata often emerges “Beethovenized,” full of stormy, even angry drama. In my opinion, the music’s distended phrases — with too much repetition of busy passagework, interruptions, and overlarge melodic jumps — display real comedy, even silliness. Too bad it’s so hard to play the notes!

The quick, rising and falling chromatic bass scales that begin Liszt’s Ballade No. 2 convince a lot of pianists to make big dynamic swells and ebbs, surging up and down. The action of the fingers can become the primary feature of the music. On the contrary, I believe these scales are best if minimized, and played with a fairly even dynamic level. The long notes above must sustain and cohere into a melody line almost untroubled by the bass rumblings. Liszt’s long, poetic pedal indication is a good clue of how quietly to play the scales. A modern player who finds it necessary to change the pedal frequently in these passages should reconsider!

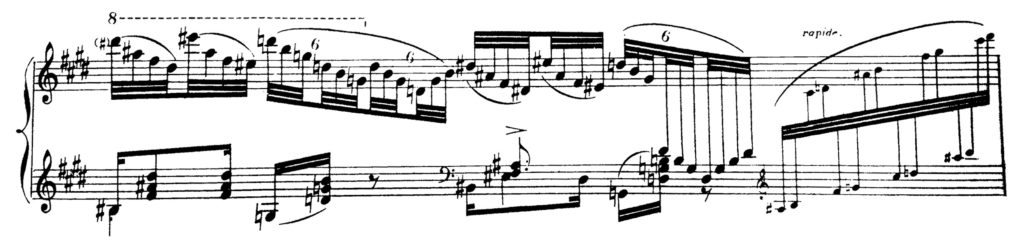

Often the presence of great technical demands leads the performer to furrowed brow, and the drama of struggle. In concerts, emotionally turbulent music may come across particularly convincingly because the apprehensive feelings of the public-performer align with it. A composer may consider how the ease or difficulty of execution affects music’s character and emotional tendency. The overwhelming difficulty of certain passages in piano music by Brian Ferneyhough (or Robert Schumann!) leads to a welcome anxiety of musical expression.

Ferneyhough: Lemma-Icon-Epigram

The opposite situation exists in simple-to-play music with extreme or intense emotional content. Some of Richard Wagner’s short piano pieces, Webern’s piano writing, or El Amor y la Muerte by Granados are in this category. The player needs to work quite hard to convey sufficient intensity, from very few notes.

Every aspect of our technique and our technical choices influence the music we make. A pianist might choose a fingering for greatest ease of producing equal sounding notes — or deliberately use a less facile fingering. In playing all those rocking thirds in Philip Glass’s piano music, I avoid my thumb.

Music written by instrumentalists bears the mark of their technique, their physical playing, their bodies. We might think of piano pieces by Rachmaninoff, or Ravel — but also Beethoven, Debussy, and Glass!

A piece like Ravel’s Jeux d’eau is revealing. In a performance of it, we hear the shape, and strengths and weaknesses of a pianist’s hand. Of course, I have practiced those arpeggios, trying to equalize the sounds of my various fingers. But in the end, does my hand follow the idea represented in the text — or lead it?