Patterns of rising and falling inflection are vital to a lot of music. Purely instrumental music often encodes emphasis-patterns that resemble speech, or song. (Linguists prefer the term “intonation” to signify these rises and falls.)

In the notation of European classical music, at least since the 18th century, musicians have used “slurs” as a means of indicating phrase groupings and stress patterns. Describing two notes written under a slur, Leopold Mozart writes, in 1756: “The first of two notes coming together in one stroke is accented more strongly and held slightly longer, while the second is slurred onto it quite quietly and rather late.” The German word “Bogen” signifies both the connecting mark known in English as a “slur,” and the physical sound-making implement, the “bow,” used in playing the violin.

In the notation of European classical music, at least since the 18th century, musicians have used “slurs” as a means of indicating phrase groupings and stress patterns. Describing two notes written under a slur, Leopold Mozart writes, in 1756: “The first of two notes coming together in one stroke is accented more strongly and held slightly longer, while the second is slurred onto it quite quietly and rather late.” The German word “Bogen” signifies both the connecting mark known in English as a “slur,” and the physical sound-making implement, the “bow,” used in playing the violin.

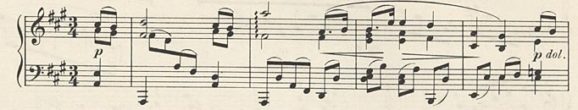

In the 1890s, Johannes Brahms was still writing slurs, sometimes combining or overlapping them. (Composers continue to write music with slurs today.)

Brahms: Intermezzo in A Major, opus 118, number 2

In the A-Major Intermezzo, the opening 2-note slurred group has falling inflection, in my opinion. (I play the first note with greater intensity than the second.) Such a two-note group references Viennese Classical-period music. This particular 2-note slurred group is also a modernism: the slur represents a “resolution” from a less dissonant, less harmonically-charged sound, to a sound of greater dissonance. That reverses normal Western European practice, the practice described by Leopold Mozart.

With how much subtlety should this slight harmonic shift (from the first eighth-note to the second eighth-note) be rendered in performance? I favor a small change of pedal — I don’t completely overlap the sound of the C-sharp and A, with the B and G-sharp. Excellent legato binding of the fingers to the keys is important in playing the notes under the slur. I might wish for a slight release of the pedal, a thinning of the sound, after that B and G-sharp and before the downbeat that’s coming.

Many players make a crescendo from the beginning of the piece, so that the second note is louder than the first. Many players pedal through the first 2 eighth-notes, creating a new “harmony” by sustaining together all of these pitches. Some musicians rush from the intermezzo’s first note into the second. These performance nuances turn what I believe is a falling inflection into a rising inflection. (With such a change in pronunciation the 2-syllable word “CAR-pet,” becomes “car-PET”!)

The intermezzo’s performance instruction “teneramente” is often translated as “tenderly.” That arises from the Latin “tener” But, I’d like to make a mistake here. The very similar Latin word “tenere” means “to hold.” And all of this (tenderness and holding) is physicalized in the hand gesture made in performing the first 2 notes of the piece — if the second note is played with a supple hand, stroking slighty away from the keys and back toward the player’s body, at the end of the slur.

Confronting musical notation with many small slur-groups, some players will be concerned about making a long “line” — not allowing the music to disintegrate into too many small units. In the notation of this piece, the long slurs and the groups of shorter slurs they overlap (mm. 3-4 for example) may signify two levels of organization. And it is possible to allow each short group to be started and finished in sound, while at the same time maintaining temporal flow across a longer span.

In a lot of European music, musical phrases with rising inflection (“questions”) alternate with phrases that have falling inflection (“answers”). Music theorists speak of “antecedent” and “consequent” phrases. This pattern can exist on multiple levels. There may be long-range antecedent and consequent patterns unfolding as quicker short-term antecedent and consequent relationships pass by.

Some linguists observe a change in patterns of spoken English. It seems there is now a greater use of rising infections at the end of a phrase or sentence — a habit of inflection associated with questions. Perhaps in our world, the proportion of questions to answers has altered? Perhaps this rising-inflection tendency affects players of the A-Major Intermezzo?

The difficulty of, or time necessary to make certain gestures at the keyboard influence the way pianists organize musical phrases. At the end of measure 1 in the intermezzo, there is a rather big right-hand jump. A player might be tempted to push down further on the right pedal to conceal a possible gap in sound, or elongation of beat. It is exactly at such a phrase-group-end, that I prefer to lighten (slightly release) the pedal. Here also, a player may be tempted to release the left-hand note early, to jump to the low bass note that follows — making subtle pedal manipulations very difficult. (Once such a note is released by the finger, a pianist will tend to hold the pedal down firmly.)

In many recordings of this intermezzo, the inflection of the falling two-note groups is reversed. Most recorded pianists emphasize, or lean into the the second note of the groups. (Almost no recorded pianists do what I am advocating.) Two recordings of the piece were made by the celebrated pianist Wilhelm Backhaus. In his 1932 recording, Backhaus does give a falling inflection to the two-note groups — adopting a fairly quick tempo overall. In his 1956 recording, Backhaus adopts the prevalent rising inflection. (He also slows the tempo, and makes longer melodic “lines.”)

This is really a remarkable series of thoughts about a piece that I thought we already knew too well! You’re disclosing that the familiar is actually strange. Thank you!!!