In performing Billy Strayhorn’s “Lush Life,” some singers deliver the subtle, and possibly difficult to pronounce word combination “distingué traces” as “distant gay traces.”

A British lawyer or Harold Bloom might call this a “misprision.” We may willfully twist a text to achieve a particular meaning. Or perhaps we are always getting it wrong. Bloom writes definitively: “Every poem is the misreading of a parent poem… There are no interpretations but only misinterpretations.”

For decades, the only available edition of Ravel’s Gaspard de la nuit included an awkwardly-difficult-to-play and erroneous passage in the suite’s first piece “Ondine” — the result of errors in editing. The corrected music appear in recent editions. Generations of pianists played and recorded the wrong notes.

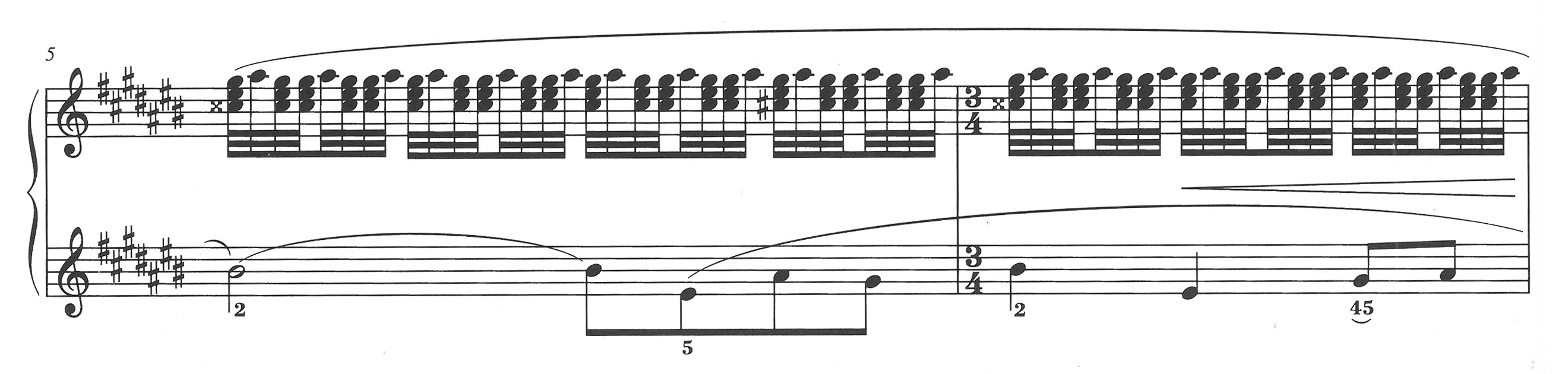

Ravel: “Ondine,” mm. 5-6 (corrected)

Recent editions of Debussy’s piano music are making known some notes and rhythms that were misrepresented for decades in the only published text…

In some instances, a misreading, or idiosyncratic reading takes hold among performers. In the playing of the Chopin’s First Ballade, many performers find 7 beats (they add an extra quarter-note rest following the third beat) in bars where the notation seems to call for 6 beats per bar…

Chopin: Ballade, opus 23, mm. 10-13

At the beginning of Brahms’s Second Piano Concerto, in the extended piano solo, most performers accommodate the right-hand sixteenth notes to the prevailing sextuplet sixteenth-notes, aligning the right-hand melody’s sixteenth-note with the last sixth of the beat. Following Brahms’s notation and in correspondence to passages where the orchestra plays similar material — I vastly prefer to play these right-hand sixteenth-notes as a quarter of a beat, not a sixth of a beat. Jacob Lateiner pointed out this issue to me. In my opinion, after consideration, there’s not much doubt of the instructions being given (the rhythm the text signifies). Yet, I have heard no pianist, other than me, play quarter-of-a-beat sixteenth-notes here.

Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 2 (I), mm. 11-12

Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 2 (I), mm. 58-59

Do the wrong notes or rhythms become the right ones? As my former student Andrew Zhou observed, it would not be correct to say that the “wrong” readings of Debussy’s piano pieces occasioned by published texts with spurious information are not part of the identity in sound of that music.

After time, preponderant readings of a text seem primary. Who will now dare to deliver the opening of Brahms’s Second Concerto with the full friction-filled intensity of the notated rhythm?

It’s certainly true that in classical music playing the way some famous pieces are played seems to have little connection to the printed music. Are musicians so lazy? So untrained in reading or in the contemplation of a text? Thank you for this post.