During October, I gave four performances in France (Paris, Lyon, Orléans, Paris) in clubs or alternative, non-classical venues. For each of these shows, the piano was amplified (some engineers prefer the term “reinforced”). Mics were positioned fairly close to the strings of the piano, the sound processed, and piped through a PA system. In one instance, the resulting sound heard by the audience was louder than what the acoustic piano could provide. In general, the goal was not loudness but increased resonance, and slight enhancement of the smallest, most intimate sounds of the instrument — sounds that otherwise may not be conveyed across a crowded room, especially an acoustically dry room.

During October, I gave four performances in France (Paris, Lyon, Orléans, Paris) in clubs or alternative, non-classical venues. For each of these shows, the piano was amplified (some engineers prefer the term “reinforced”). Mics were positioned fairly close to the strings of the piano, the sound processed, and piped through a PA system. In one instance, the resulting sound heard by the audience was louder than what the acoustic piano could provide. In general, the goal was not loudness but increased resonance, and slight enhancement of the smallest, most intimate sounds of the instrument — sounds that otherwise may not be conveyed across a crowded room, especially an acoustically dry room.

Karlheinz Stockhausen came to believe that the acoustic piano — the “string piano” he sometimes termed it — should be amplified in live performances, “to make the timbre nuances audible from all seats in the auditorium,” as the website karlheinzstockhausen.org explains. Perhaps, today’s listener is so accustomed to reinforced, processed sound that the bare, raw sounds of the piano need a bit of Lévi-Straussian “cooking”?

Amplification remains rare in classical music performances. Concert halls are themselves musical instruments, resonating and “amplifying” sounds. The relatively drier or even dead acoustics of many pop music venues can be understood — as balance, blend, and resonance are achieved not entirely by the band on stage but with the significant participation of a sound technician/engineer/artist mixing at a console.

At (le) Poisson Rouge in New York City, I have played many amplified shows. The relatively dry nightclub acoustics are not too flattering to piano music. The sound engineer is a vital part of the performance.

Pop musicians are accustomed to monitors, small speakers on stage aimed so the performers hear something of the mix the audience hears. Classical performers may be confused by sound from a monitor. One of my chamber music partners at LPR asked that the monitor be turned off.

Another excellent player I performed with in an ensemble at LPR strongly tried to resist any amplification. It seemed almost a social issue, or some elite coveting of heirloom-variety, “organic” food instead of processed food for mass consumption…

As Stockhausen observed, microphones are instruments. Mics and sound boards and speakers can allow us to hear, but never neutrally. A microphone makes a reading of sound, it has a characteristic response pattern, a certain hue. My favorite mics for recording piano music are made by DPA. For live applications, it is often necessary (in order to avoid feedback), or convenient, to place mics rather close to the piano’s strings. In October, in each club, the mics that were available (as well as the particular mixer, reverb program, and engineer) became part of the sound that I made for the audience.

In miking a piano, achieving a balance across high and low registers is crucial. Besides trying parts of pieces, during sound checks, I usually play some slow scales and listen to hear whether one register is particularly boosted or subdued. Some EQ may be helpful, or an adjustment of mic placement.

Electricity brought about many changes in music, changes we are still reckoning with. Once, music was sound in the air, now it’s usually mediated by current, digits, or signal. The faint acoustic sounds of an electric guitar are made to be picked-up and transformed. Perhaps, I’m trying to turn the Steinway into a Stratocaster!

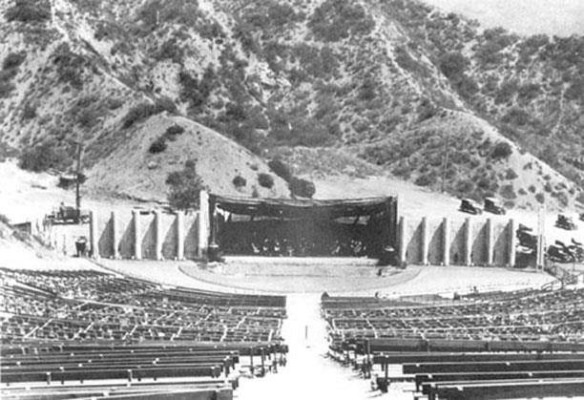

In some venues where voices and instruments once projected only acoustically (Broadway theaters, Tanglewood, the Hollywood Bowl!), amplification is now always used. With use of high-power amplification, stadiums and sports arenas become venues for bands.

Many of today’s public performances and performers may be less presentational and more confessional in style and tone — than were the unamplified.