As I started working on Morton Feldman’s For Christian Wolff, I aimed to learn the notated rhythms accurately. The published score is a reproduction of Feldman’s handwriting. Some things puzzled me. There are a few measures that don’t add up to the expected number of beats (mistakes?).

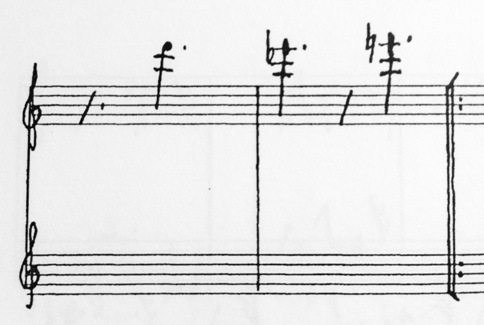

(The top staff is the flute part. The lower staff is the keyboard part: notes with stems up, played by the keyboardist’s right hand on the piano, notes with stems down, played by the left hand on the celeste.)

In other measures, the flute part and the keyboard part are not rhythmically aligned.

I talked with Anthony Coleman. He expressed his opinion that in performing For Christian Wolff, fastidious alignment of the beat in the flute part and the keyboard part might not be important. At an early stage in working on the music, I couldn’t agree.

For decades, the classical music community has held the shared belief that pitches and rhythms written by a composer ought to be performed accurately. The level and nature of that accuracy is less clearly agreed upon.

In the playing of difficult new music, getting the pitches and rhythms right can be challenging or impossible to achieve. I’m imagining first performances of The Rite of Spring or Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony — indeed, any symphony by Beethoven. It’s a good guess that all these performances were, by modern standards of accuracy, deeply flawed.

As musicians struggled to bring coherence to a complex piece by Milton Babbitt, he quipped, “Life is short and my piece gets long.” Apparently the players couldn’t go fast enough for the music fully to make sense. One of my students performed Salvatore Sciarrino’s De la nuit, coherently playing it in about 5 minutes. A celebrated performer of contemporary piano music played twice as slowly…

When I first became aware of Debussy’s D’un cahier d’esquisses, I was listening to a recording by pianist Walter Gieseking. Later, looking at the notation of the piece, I realized that Gieseking reads a note in the penultimate measure as if it was written in treble clef (it’s a bass-clef note.) I rather liked the “F” Gieseking played — and in my ear it had primacy.

Charles Rosen speculated that a pianist wishing to give an “authentic” performance of the difficult beginning piece from Robert Schumann’s Carnaval would need to play several wrong notes. Mr. Rosen reasoned no players of the period were capable of modern “accuracy.”

Do the notes in a written composition represent what the listener should hear? Or, perhaps written music merely puts the performer into a condition for making music? The composer (of famously difficult music) Brian Ferneyhough has written:

“What can a specific notation, under favourable conditions, hope to achieve? Perhaps simply this: a dialogue with the composition of which it is a token such that realm of non-equivalence separating the two (where, perhaps, the ‘work’ might be said to be ultimately located?) be sounded out, articulating the inchoate, outlining the way from the conceptual to the experiential and back.”

And then the effects of a notation (fixed in writing) change, as new generations of musicians read it. The resulting music necessarily changes, and keeps changing. So it is, in reading any sacred text. Even if the symbols remain the same, their signification (what they signify) cannot remain the same.

For much of my life as a classical music performer, I believed that a mistake-filled performance of a piece was not really the piece. A performance either was the music or it wasn’t. Simple.

Now though, I’m going to say something else. All the sounds that result from a written piece (from a musical text) are the piece. All performances ever given add up to the identity of that music. Such a range of results represents a limit of all possible musics that might be made. In this way, a composition is never finished, but always subject to further completion, understanding, exploration.

Sound recording gives a glimpse of the range of music achieved by particular performers reading a particular text in a limited time-period.

Paula Robison and I gave four performances of For Christian Wolff, in March. Listening back to the recordings that were made of each performance, I have to say that some of the most satisfying music-making seems to have occurred when we were not “together,” in a conventional sense of that concept.

Anthony may have been right.

By ‘not together’, do you mean not playing what the score called for? Or the parts in the score that were not rhythmically aligned?

If the latter, that was surely one of the great achievements of Feldman’s later work. The repetition that wasn’t really repetition, as the same clusters of notes were sounded, but the relationship between instruments constantly shifted.

If the former, super!

Nice post.

Thanks, Bruce. This is excellent.

For me, this idea becomes convincing as we listen to some of the recordings of the past and compare them with the technically proficient and sonically balanced interpretations captured on disc today – for example, Egon Petri’s recording of Schubert’s Erlkönig in Liszt’s transcription. Pianistically speaking, Petri’s rendition may not be the most successful (he was no longer in his prime when he made this record in 1951). But despite what would be viewed today as some technical shortcomings, his interpretation successfully conveys what modern pianists seem to fail to portray adequately in the chilling final scene. Paradoxically, it is Petri’s technical unreliability that charges the final page with true blood-pumping terror. The halo of extra noise produced by the sonic interference of occasional wrong notes creates an astounding effect. No pianist today manages to achieve equal ferocity, fury, and emotional power. It may be the technical accuracy commonly delivered (and expected) today that prevents them from doing so.

I wonder whether Liszt’s playing featured the same degree of textural uncleanliness. Perhaps Heine’s words upon hearing Liszt (“I no longer know what he played, but I could swear that it was variations on a theme out of the Apocalypse. At first I could not see them distinctly, those four mystic animals, I could hear their voices only, especially the roaring of the lion and the screeching of the eagle”) referred to sonic effects that a degree of technical imprecision helped to achieve. And if it was indeed the case, the outcome may have had a specific relevance in the listener’s experience. It would be the greatest of paradoxes: in the end it may have been textural uncleanliness, against Thalberg’s refined and accurate playing, that prompted Cristina di Belgiojoso to proclaim Liszt as “the only pianist in the world.”