“Down below, in the dark of the street lamps, Eusebius said, as if to himself: Beethoven—what lies within this word! Beautifully, within the deep ringing of the syllables, sounds an Eternity.”

(“Unten im Laternendunkel sagte Eusebius wie vor sich hin: Beethoven — was liegt in diesem Wort! schon der tiefe Klang der Sylben wie in eine Ewigkeit hineintönend.”)

— Robert Schumann, 1835

Also, this begins with a statue.

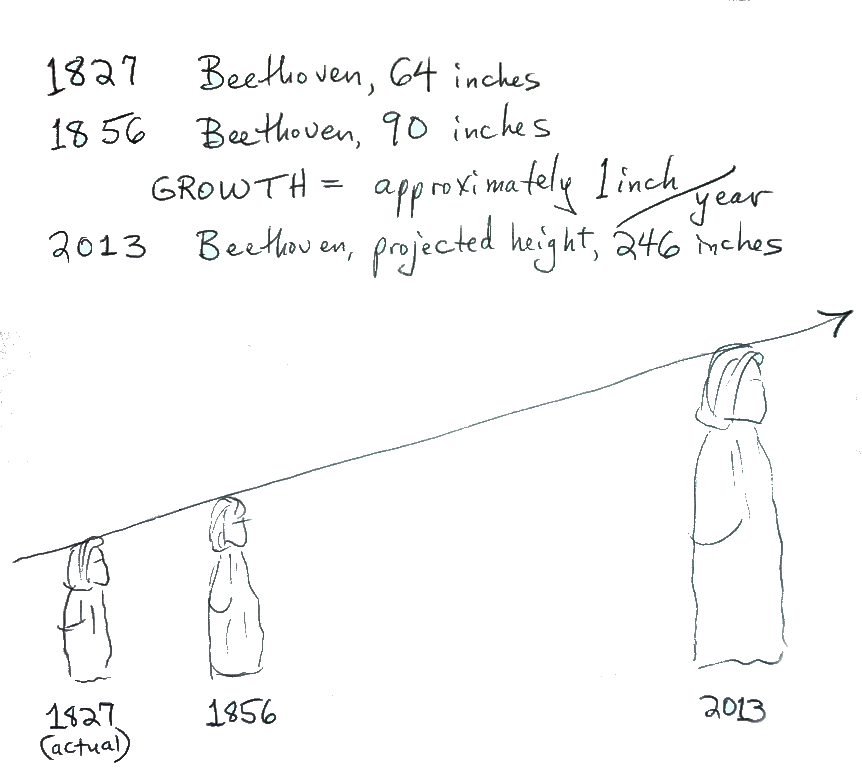

Every day I’m in the Jordan Hall building in Boston, I see it: a massive bronze sculpture of Beethoven. The person Beethoven was about 5 feet, 4 inches tall. This metal one is 7 and a half feet, and stands on a 3-and-a-half-foot-high marble base, in the Jordan Hall lobby.

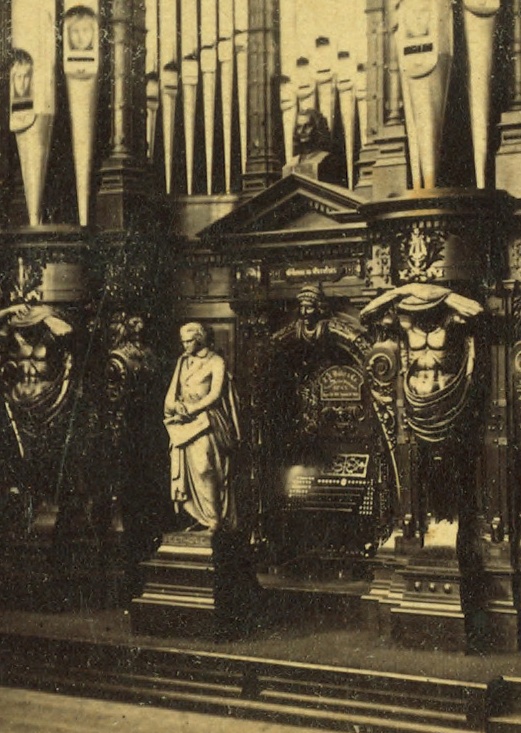

Thomas Crawford: Beethoven, 1854

During three years that I played chamber music in the Gewandhaus in Leipzig, another imposing (and fanciful) Beethoven stood watch in the lobby there; it’s moved now.

Max Klinger: Beethoven, 1902

The Boston Beethoven was on the stage of Boston Music Hall until the end of the 19th Century. He shadowed the premiere of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto in 1875…

When Boston’s Symphony Hall was constructed, the statue didn’t move there. Instead, on a gilded medallion, at the apex of the stage’s proscenium is a single word — it’s the stand-in for the statue.

By the early years of the 20th Century, the big Boston Beethoven was inside the front doors of the new Jordan Hall — a familiar face for concert-going Bostonians entering the venue.

Other big Beethovens are standing watch…in New York,

in Bonn…

There are so many renderings, receptions, deconstructions — it’s daunting. Life is short, and Beethoven is tall! His identity and the identity of the music that he scripted grows bigger with each word, every casting, with every next performance.

Mauricio Kagel: Ludwig van, 1970

Do I fear the Boston statue will come to life Commendatore-style and summon today’s classical musicians down to Hell? Perhaps I fear the statue won’t come to life? It seems certain to me that if the statue was removed (I’m not suggesting), the music-making being done within the building would be at least a little different. Similarly, classical pianists should be happy Beethoven lived in the pre-sound-recording era. The existence of recordings of Beethoven’s piano-playing would surely compromise the careers of many…

As Scott Burnham and Tia DeNora show, Beethoven is a construction, in which we participate. The identity of canonic music keeps changing as more and more people hear, play, and encounter it. As those musical circuits are completed by successive listeners, the art changes, growing bigger, wider.

Here, in the postmodern epoch, I find Mannerism in Beethoven’s texts. Earlier musicians sometimes turned what I consider Beethoven trifles and jests into C-Minor-seriousness. I’d call such readings “Beethovenizing.” Future readers are likely to see and hear still differently.

At the rate of growth suggested by Crawford’s monument, a new Beethoven made today will need to be 20 ½ feet. That’s using an arithmetic rate of change. If the growth rate is geometric, it may need to be much bigger…

Wow, hahaha! Are all the great American pianists also excellent comedians? You and Jeremy Denk could do a stand-up routine.