Is written music a set of instructions?

A student asked my opinion of a performance he described. In the performance, a pianist used the pedal to sustain long notes while taking his fingers off the keyboard. After thinking, I wrote:

“I think the use of the pedal for sustaining notes or helping with legato depends very much on what music is being played. For me, in music by Brahms or Mozart, the central Germanic repertory, long notes must be held with fingers — no matter what the pedal is doing.

“In later Russian or French music it may be different. You might make the sound by removing your hand and sustaining only with pedal.

“The ‘proof’ would be that Beethoven, for example, notates short bass notes (‘Waldstein’ sonata, last movement), that are indicated to be elongated with the pedal. (He’s notating what the player does with the hand.) While Debussy (in something like ‘Hommage à Rameau’) writes long-value notes that can only be sustained with pedal. Even though he makes no mention of the pedal at all. Debussy’s notation is not showing how to use your hands or feet — it’s more of a sonic picture.”

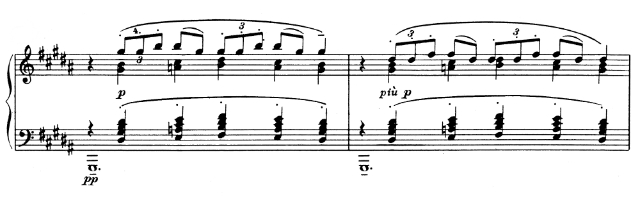

Beethoven: Opus 53, movement 3

Beethoven: Opus 53, movement 3

This is much more than a matter of how to use the pedal in piano music. What is written music? A how-to guide? A blueprint? And what kind of a blueprint? If I’m giving indications to builders who are making a structure of familiar type and in well-known conditions, I may need to convey less, or convey it differently. If my plan is for something unprecedented, the recipe takes on different significance.

Does musical notation show effect or cause?

The thing that I notice about certain sheet music is that 5 different pianists can make the same notes sound 5 different ways. Why I believe sheet music is a good tool, it cannot be traded for a teacher who can describe the “feel” of the actual notes.

I don’t mean to be rude, but please use the correct “repertoire” instead of the word “repertory”.