There is music that suffers in performance from conventionally good music-making. Mainstream classical playing seems to rely on clichés of “musicality” — arching every phrase, breathing between groups, tracing all those lines up and then down again. Some pieces need different treatment.

The first movement of Beethoven’s Opus 101 is an extended, wordless run-on sentence. Theoretically, we may understand that no satisfying cadence in A major occurs until the very end of the movement. But what player has the gumption, the courage, to play this music like your friend’s long, winding story, a tale that really won’t end, won’t resolve, won’t let in enough air — so you’re in suspense, so you can hardly form other thoughts, so you can’t get a word in edgewise?

In a masterclass, Alfred Brendel observed that too much dynamic tapering of lines (played on the piano) runs the risk of separating the softest notes into what seem like new phrase units. (Under consideration was the beginning of Schubert’s B-flat Sonata, D. 960.) Less shape may better preserve linear continuity, and voice-part integrity.

As I understand it, this relates to what Mr. Brendel so highly values in Alfred Cortot’s 1933 recording of Chopin’s E-Minor Prelude. In this recording, according to Brendel, Cortot manages to sustain independent continuous strands of texture.

With each piano there is the question of how much timbral change the instrument manifests between a loud note and a soft note, and how much the left pedal colors the sound, if the left pedal is to be used extensively. In piano playing, very soft notes at the end of a tapered phrase can too easily seem to belong to another “voice.”

I believe the new low “E” on Beethoven’s new clavier motivated him to cast the Opus 101 Sonata in the key of A — where E would be the dominant harmony. The incredible harmonic withholding and stretching of gesture through time in the sonata’s first movement fits well in the big picture of the piece, but especially so if we can render it without real pause, without conventional breath organization, running it on and on and on, hovering, until the oddity of this discourse becomes palpable.

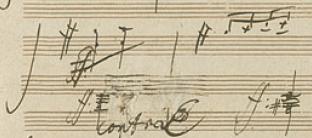

Beethoven: Opus 101, last movement