In playing piano duets or two-piano music, just being together is particularly challenging. The beginning of the sound of a note played on the piano is definite and sudden. What might pass for good ensemble playing in the performance of a piece for violin and piano (with the violin’s characteristically less-instantaneous note-beginnings), will be unsatisfying in 2-piano playing. Pianists playing together become note-arrival authorities.

As I was rehearsing with Ursula Oppens for our recent performance and recording of Meredith Monk’s piano music, a few passages were particular puzzles. Some apparently simple rhythms — when played “idiomatically” — fit together only with considerable attention.

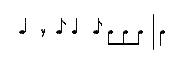

One such passage is near the beginning of my 2-piano transcription of “totentanz” from Meredith’s large work impermanence:

The top staff is played by one player, the bottom two staves by the other player. We found that the rhythm pattern of the upper part is not satisfying if the eighth-notes are played very evenly, as subdivisions of the quarter-note pulse. An aesthetically better (?) rendering quickens the eighth-note pairs and may begin them very slightly late, or end them slightly early — in the first measure, the eighth-notes begin slightly late, for example.

I invite you to try playing the upper line in a way that satisfies you.

None of that matters too much to staying together, until measure 3. In the first two bars, the lower part has long notes, and they can be coordinated with the upper part, even if compressed eighth-notes are played. In measure 3 though, the lower part has eighth-notes (a kind of demented waltz-upbeat figure) that need to arrive on a precisely-together downbeat at the beginning of bar 4.

What I believe I learned is that if the lower-part player mimics the duration of eighth-note that’s played in the upper part in bar 3, it will not quite work. The lower-part player is likely to come in with eighth-notes that are too fast to fit with what’s going on above. In practice, the eighth-notes played in the lower part are probably going to be longer in duration than the eighth-note that’s heard in the upper part…

Listening for a compound rhythm made of the moving notes in both parts (in measure 3) can help, if you recognize that the durations of the various eighth-notes are not going to be equal:

This isn’t exactly a matter of performance practice. It is a matter of interface between music, and performance in time. Perhaps that’s what “performance practice” is? But we might add something: in time, and “of a time.” Come back in twenty years, the passage may need to sound different.