In earlier museum practice, shards of ancient decorated pottery were pieced back together with missing sections reconstructed and plausible designs painted in. Missing parts of an image were supplied by restorers.

As exhibited, those restored vessels had complete surface decoration. Some fragments were antique; the rest, the painted-in parts, made a whole pot look as it might have before it was broken.

Today, it’s more likely that the missing parts of an amphora will be rebuilt with clay of neutral tone and left undecorated. The resulting reconstruction is an obvious patchwork — the antique shards have decoration while the rebuilt parts are plain interruptions in the design, clear evidence of what is lost.

Today, it’s more likely that the missing parts of an amphora will be rebuilt with clay of neutral tone and left undecorated. The resulting reconstruction is an obvious patchwork — the antique shards have decoration while the rebuilt parts are plain interruptions in the design, clear evidence of what is lost.

With the greatest admiration, I have termed the exceptional musician Robert Levin a “Mozart impersonator.” (He doesn’t deny it.) Bob’s tour-de-force renderings of Mozart’s piano concertos, with spontaneously-made cadenzas and ornamented passges, are amazing, musically fine, and provocative.

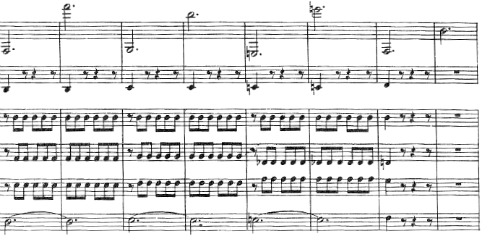

Eighteenth-century piano concertos were platforms for extemporization. Mozart and professional musicians of all kinds added extensively to written texts in performance. Or, alternatively, written texts only represent the music as general, simplified, or essentialized guide.

The recent neutrality of the museum curator seems to correspond to the musical performance practice of the 1950s. Rudolf Serkin “left blank” the rather obviously missing figurations in the last movement of Mozart’s K. 482. He played the written long notes, but otherwise let the neutral clay show.

Mozart: K. 482

Leon Fleisher holds to this mid-20th-century thinking, in his recent book, in a discussion of Mozart’s C-Major Concerto, K. 503 (another piece where some notation is abbreviated):

“There are these great leaps in that second movement of K. 503, where the piano line jumps an octave or more. Tradition, and the musicologists, will tell us that a pianist in Mozart’s time would have filled in those gaps with little improvised scales and arpeggios, those small musical gestures known as ornaments… I think a musicologist and pianist like Robert Levin, who is a master of Mozart scholarship, would probably present an almost irresistible case for filling in those spaces. But I won’t do it.”

To extemporize in 18th-century style with rigorous limitation — to exclude any harmonic practice from later times, for example — is a virtuoso act of restraint. And bears scant ressemblance to what players of the 1780s did using their full resources (even if the results manage to sound similar).

Levin’s ornamental filling-in is a decidedly post-modern action. Not leaving bare what cannot be known, but speculating and surmising — is a sophisticated act of appropriation. Even heavily circumscribed, improvisation is a living practice. Though we may wish to breath the musical air of the 1780s (or the 1930s) — to seem to do so is to appropriate.

This is a great post. I would only add that in historic preservation circles -both for conservation of objects and of buildings and even landscapes – there is not only an ‘original’ and a ‘present’. Architects like Herzog+de Meuron – at the Tate Modern and now the Park Avenue Armory in New York – conceive of preservation as showing the nicks, scars, previous judgments of the ‘fashionable’, and general treatments along the continuum of time between origination and the present. I’m not sure how this could be expressed in a single musical performance, but it would be fascinating to hear a self-conscious effort to do so.

Leon Fleisher’s attitude I can understand. Despite the fact that most of my work has involved improvising, and for many years I was really interested in graph scores, I still think improvising in the Classical or Romantic repertoire is just not right. Personally I think the long notes are preferable and give it a slightly unusual character.

Another fascinating post, thank you.

I have heard Levin speak on Mozart and the piano several times, most recently about the cadenzas in the Piano Concerto No. 23 (followed by a performance with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment). He gives convincing reasons for his approach to Mozart’s piano music and the use of improvisation and ornamentation, and I have never felt he is imposing his own personality on the music (at least not in an obvious, egocentric “look at me!” way). We have grown used to a “one way is the right way” delivery of music: Levin’s approach is refreshing and thought-provoking.

More on Robert Levin & the OAE here http://crosseyedpianist.wordpress.com/2011/10/06/an-evening-with-robert-and-wolfgang/