When I sit at the piano to play a composed piece I’m matching myself against a pre-determined set of musical requirements. Right?

When I sit at the piano to play a composed piece I’m matching myself against a pre-determined set of musical requirements. Right?

I’m trying to meet expectations or even excel to deliver a faithful account of the composition. If that’s true, then one performance can be better than another. A performance with many faults might even fail to represent the piece that’s written.

What is that faulty music? Can it be overlooked or ignored, put out of the mind to be replaced by better more accurate renderings?

Many classical players want to banish mistakes, slips, and gaffes from performing. We may often sense a big gap between our best work and an “off night.” Richard Goode has said that between a performer’s best and worst playing there’s a difference of no more than 10 per cent. Heard from afar, those off nights are rather similar to our triumphs.

After an unsatisfying performance we may console ourselves with the thought we can do better next time. But, I suggest, there is no next time.

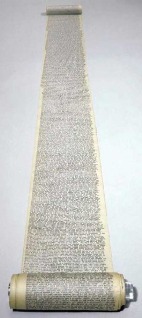

There is no next time, because when we go to the instrument to play again we are not starting over, we are continuing. Our whole lengthy playing of our instrument, our practicing, and concerts — all together they form one music-making. Our musical life is one event, an artwork and a craftwork, unique, unrepeatable, and to large extent irretrievable.

Stockhausen believed that his musical compositions were not separate. They belonged together as some kind of metapiece. I’ve suggested even that the piano playing of all music makers can be heard as forming a single pianoscape. So then we are responsible even for the wrong notes of our least-admired colleagues!

It’s an issue of conception, even in regard to an individual pianist performing a single work repeatedly. Encountering Gabriel Chodos playing Beethoven’s Opus 111, it seemed clear to me — as he started playing, he was not beginning the music but continuing it.

In an amusing, disturbing scene from Mauricio Kagel’s film Ludwig van, a lifetime engagement with a piece (or its entire society-wide performance history) is invoked as an aged pianist, through apparent “time-lapse” photography, is seen to grow several feet of additional hair while playing the first movement of Beethoven’s “Waldstein” Sonata.

While some might wish to set aside certain performances, a few musicians collect, preserve and even distribute everything they do, through recording. The Borromeo String Quartet offers an example — or The Grateful Dead and the band’s “tapers.”

In our technologically enabled world, is it going to be long before some musician’s playing (metaplaying) is entirely documented through recording — from first note played in childhood, and including every minute practiced, rehearsed, performed? So far, this lifelong metaperformance is carried around only inside our heads.

As we make music, what happens next cannot really alter what we have already played. We recenter and recontextualize but don’t retract. Though we may seem to be satisfying a task, we are spinning in time — continuing our musicking, singing on and on into the space we find ourselves in.

“singing on and in into the space” !!

I’ve always felt that learning and playing music is a continuous process, both as a learning experience and a voyage of discovery. A piece can never really be “put to bed” once and for all, though one may feel one has reached an end point when a piece has been performed. Put a piece aside for a few weeks or months and then return to it and new insights and ideas emerge. I love the way music continues to surprise us, even a work that is very familiar, that we have lived with for a long time.