A distinguishing trait of Mozart’s music is rapidly and frequently changing character, Affekt, or mood. He’s a quick change artist.

For the 21st-century listener, it’s simplistic to hear only a single unvarying Affekt or character in an entire movement of old music. We tend to hear the changes.

Mozart’s music may offer an extreme, an almost constantly shifting and evolving rendering of human state-of-mind. It’s classical-sonata juxtaposition of multiple ideas within one tempo — carried very far. This is the newness of Mozart’s music, and it’s lingering appeal. And it resonates with our experience. Walking down the street, how many feelings do you feel? How many thoughts cross your mind?

Performances are not usually rich enough to convey all this chameleon-like behavior, all this morphing and change. So much playing of classical music offers generic, smoothly-wavy beauty. A pretty, bump-free luxury car ride. It’s easier.

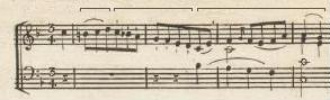

In the opening phrase of Mozart’s Variations, KV 613, I’d like to hear three or four distinct “Affekts.” Their delineation — these quick changes — can be manifested in sound but is rooted in rhythm.

The initial quarter-note-note upbeat is an entrance into the music — a transition from outside to inside, a passing through the frame. It’s an invitation. It’s a kind of Eingang. Its length can be more than a quarter-note, if we’re measuring by two of the eighth-notes that follow. With this anacrusis, this note of entreaty, beated time hasn’t quite started yet, in my opinion.

The slurred three-note ascent begins with a distinct onset of sound at its first note, a chromatic alteration, a consonant, a tone made as the bow begins a down stroke. This three-note group — a three-syllable word or a melisma — ends with a gentle unaccented tapering. The chromatic resistance dissipates in the going up. For me, the highest D is tenderly not-staccato. The following, falling staccato eighth-notes make for a long, unaccented suspense-of-beat, and are less emotionally expressive (back to B flat) than the first three-note group. (Seven chuckles, or laughs?) These notes do not lead to what’s coming. They follow from what has already happened.

When the upper solo line is joined by lower parts (when the band comes in, at the end of measure 2) the music is suddenly strongly beated, less personal — for me, best if almost comically rigorous.

In the postmodern, generalized playing of classical music, long phrases are often spun with slightly hesitant rhythm at cadences. Far more satisfying here is relatively beatless solo delivery at the outset (mm. 1-2), followed by stricter beating with the arrival of ensemble texture, and right through the cadence.

“[Satie’s Parade] may offer an extreme, an almost constantly shifting and evolving rendering of human state-of-mind. It’s [dadaist] juxtaposition of multiple ideas within one tempo — carried very far. This is the newness of [Satie’s] music, and it’s lingering appeal. And it resonates with our experience. Walking down the street, how many feelings do you feel? How many thoughts cross your mind?” 😉