Some solo piano music has part-writing that seems to correspond directly to music for string quartet. In such keyboard music, there are a constant number of “voices” tracing coherent individual lines.

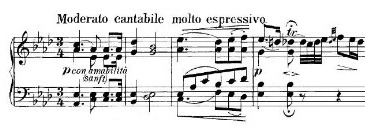

Beethoven: Opus 110

Beethoven: Opus 110

These voice-parts have integrity. We can follow tenor or bass, alto or soprano (viola or cello, second violin or first violin).

This is a modern practice in keyboard music, I believe. The earliest keyboard pieces — intabulations based on vocal music — are not so fastidious. Parts come and go.

In such later “original” keyboard music as Frescobaldi’s toccatas, keyboard writing that mimics integral, close-position voice parts is juxtaposed with more fantastic passages in which “voices” appear and disappear as texture thickens, or clarifies.

In realizing keyboard accompaniments on the harpsichord (from figures), the player may add more notes to balance a dense texture, or thin out the “part-writing” in a spare context. This extemporaneous practice is notated in the keyboard music of J. S. Bach. At cadences, additional voices may appear. Thicker chords weigh down the texture, perhaps allowing the music to pause or stop.

In this way, the writing in the Arioso in Beethoven’s Opus 110 looks Baroque — with more voices present at cadences. This archaicism is perhaps also a futurism?

In 19th-century piano music, thickening and thinning may involve the signification of adding and subtracting voice-parts. In other instances, something else is going on.

In 19th-century piano music, thickening and thinning may involve the signification of adding and subtracting voice-parts. In other instances, something else is going on.

As I’ve discussed, piano music may (with several notes) signify the sounds of a singer beginning a single note. In Ravel’s Concerto for the Left Hand, a remarkable effect is notated. (The pedal is indespensible to making this music work.)

In this phrase of music written by Ravel, the apparent arrival of the three-note chord in the upper staff is not really an addition of voices. It is entwined with the complex sonority and texture of strands of the texture going in and out of alignment. It may be a reference to a complex brass timbre — not a clear focused tone, but an almost choked note, rich in undertones. These apparent voice-parts may be the notation of a timbre! A sound with friction, a sound with drag and grain in it. A jazz trumpet tone engulfed in the thick air of a smoky boîte… (Once again, “les sons and les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir…”)

Interesting comments on piano writing through the ages, I have always loved the florid runs of Tudor music. When I first played that music I thought it was quite anarchic, the way florid passages appeared almost at random (or so it seemed to me).

Do you think that the technique of writing largely four part harmony, generally with correct voice leading, but with parts being added or subtracted, is the perfect way of adapting an ensemble or vocal ensemble style of writing to the piano?

If the vocal ensemble style we strict it may appear unpianistic and I think the best piano transcriptions are those that are adapted to a pianistic style, rather than being literal.