Is the most famous classical music so familiar, so often performed, that it’s worn out? I’ve listened to Beethoven’s “Appassionata” so frequently that it’s rather difficult for me to hear the music, to accurately sense the real sound patterns being made on a particular occasion. (The mind slips into a “this-is-how-it-goes” mode that dulls perception.) Are icons like the Fifth Symphony or the opening of Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana being used up as they saturate our consciousness?

Technology makes it ever easier for us to hear recorded performances of the past, and recordings by a wide range of contemporary players. It may seem there are not many new possibilities left in the playing of famous pieces in the canonic classical repertoire.

Before playing Chopin’s Third Ballade for me, a young pianist mentions jokingly that he recorded himself in practicing and that his playing sounded “about like Krystian Zimerman.” Then, allowing I might not approve, he says he listened to several other recordings of the piece made by celebrated past virtuosos, including Vladimir Horowitz and Sergei Rachmaninoff. We agree that none of these renditions are really good — if closely compared to what’s notated in Chopin’s texts. (Perhaps the aim of this playing is something else?)

The extraordinary detail and particularity, even peculiarity, of music notated in classical scores gets leveled out in many performances. So, in the playing of famous music are we almost all done? Or have we barely begun?

Learning to play “musically” usually means absorbing clichés. In modern playing that may mean taking time at cadences, rushing ahead in loud dramatic passages, getting louder as a melody ascends… Aside from the particularities of specific pieces, there are already troubles in this list — even if merely generic playing is the goal. 18th-century phrases might end with less time taking than in the expressive twists that occur just before an ending cadence. Pre-19th-century melodies may tend to lighten as they go up. Chopin, at least, is reported to have moved ahead in quiet passages — quickening the delivery of material that was less important.

Careful reading is not a matter of pedantry. Piano music often calls for textures or sustained tones that seem impossible to achieve in terms of physical sound. The opening of the Third Ballade intertwines speed, physical loudness, and phrase direction so closely that it’s hard to consider the elements independently.

If a sense of “falling-pitch-equals-dynamic-tapering” leads me to play the long E-flat, in measure 2, softer than the higher F that precedes it, or even to emphasize the F — I probably will not manage to get the E-flat to sustain enough. (Or if the basic “Allegretto” is too slow.) If my artistic whim, or the absence of an indication for reduced dynamic level, leads me to deliver the tenor answer in bar 3 with mezza voce tone equal to the soprano line in m. 1, or expressive lingering I will not realize the long (unbeated?) soprano note above (a dotted quarter-note tied to a dotted half-note tied to another dotted half — that’s one long-breathed vowel!). Speeding up, and significantly lightening the tenor line, in m. 3 and m. 4, is a possible strategy for trying to achieve Chopin’s long note. (A rubato inferred from the notation — from the challenge that’s proposed.)

The direction of line through the opening 2-bar phrase (end-directedness), through the F to the long E-flat turns out to pervade the Ballade. Chopin’s slightly enigmatic double stemming in the coda, is still pointing up this basic (syncopated) design.

The direction of line through the opening 2-bar phrase (end-directedness), through the F to the long E-flat turns out to pervade the Ballade. Chopin’s slightly enigmatic double stemming in the coda, is still pointing up this basic (syncopated) design.

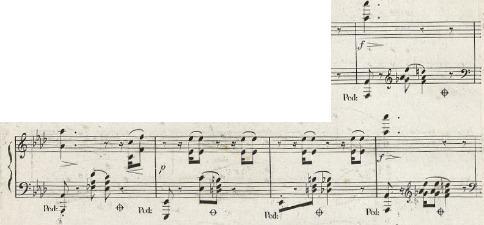

Among vocal significations in the piano writing, are a series of unusual-looking two-note droops. The way the two-voiced units are slurred down to single notes may not represent good voice part integrity. It is a piano-translation, of a kind of fully resonant sung notes (with lots of ressonance/overtones) each brought down to a quiet breathy whisper, an Italian bel canto soprano nuance:

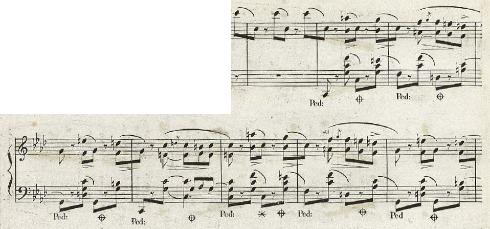

The changing and unexpected pedalling, as it is marked, is a lesson in phrase delineation, management of sonority, and blurring in the service of making some moments of time matter less.

The changing and unexpected pedalling, as it is marked, is a lesson in phrase delineation, management of sonority, and blurring in the service of making some moments of time matter less.

Sudden, unexplained shifts from forte to piano help organize the Ballade’s phrase structuring. In bars 9 and 10, A-flat is proclaimed and answered by subdued, nearly parenthetical rhythmicizing of E-flat, in mm. 11 and 12. What pianist has the temerity, the hardihood, not to smooth out or ignore these dynamic shifts, to keep working at them until their strange beauty and sense emerge?

Chopin: Ballade in A-flat Major, opus 47, mm. 9-13

“Is the most famous classical music worn out?”

– Yes!

I am just trying to get my daughter to listen to recordings of the music she is playing!!! She is 12, working on Chopin’s Prelude in E Minor, the Fur Elise, and Bach’s Inventio #8. At her age I think she needs to listen to iconic recordings.

But your point is well taken…with the ability to listen to hundreds of versions of the same piece….you have to ask “Is that all there is???” Your mind just glazes over at one point.

So thanks for reminding us that close readings and analysis make a difference. And it is not stodgy to just plug away to see if something new is revealed – at least for the student of piano himself.

I have a 35 year old renter who likes opera but avoids sysphony concerts because they are boring. Why, same music over and over, musicians dressed in black like 19th century servants, no relationship with the audience. When I asked why it was boring one reply was because it is always based on German music, nothing with American ragtime, jazz, etc. No American composers but Beethoven over and over, no South American composers but Brahms again and again. The same concertos again and again.

Enough said

In my adolescent years, my teacher/mentor required that in depth score study and discovery must precede any recorded listening. Now of course, for many compositions my ear had already been exposed to other ideas. Later, through graduate study and beyond the combination of study, analysis, discovery, and listening combine. Yet how to move beyond the bias of the ear and re-discover or re-define is the question and to me answers the question in this way. . . barely begun.

Yes! I have, because I worked as a symphony musician for 40 years. Because we can’t hear musical feeling when we know too well what is to come, we aren’t hearing the music as it was intended to be heard, as a carrier of meaningful expression. And your wonderful comments about style technique means we have to also to know our history, and the politics and situations of the people for whom the music was (partly) written. Whether it’s Baroque or Romantic, the style was the current for that carried the feeling and the meaning of the music. We can argue I suppose, that being creatures of our own time, does recreating their style allow our audiences to take in this art today in any fashion different than the person who goes to the museum and stands amazed at a relic of paleolithic art? Is this enough? What about today’s writers who are using (hopefully) our current multi-cultural awareness to create today’s sounds. I think it’s driven after all by personal experience (which is another way to say education). If someone has heard enough, let them go where music is new and exciting to them!

In my personal experience, about 10 years have to go by without a single listening before a piece that has gone stale for me regains its value.

But don’t forget that there are always people being exposed to this music for the first time. Watching my son’s face as he listened to the 1st movement of Beethoven’s Fifth reminded me why the piece is special.

Meanwhile, there are always (ahem) living composers creating new pieces—some of which will be worth listening to until they become stale…

David Wolfson

http://www.davidwolfsonmusic.net