In his anxiety, Johannes Brahms read the slow movement of Ludwig van Beethoven’s piano sonata, opus 10, number 3,

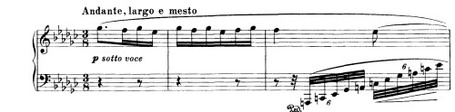

and penned his own intermezzo in E-flat Minor, opus 118, number 6:

(If D goes to C-sharp, then D Minor can go to E-flat Minor. Up can be down. 6/8 and eighth-notes, or 3/8 and sixteenths. Largo e mesto. Dies Irae? D-Es?)

Earlier misprision led Brahms from playing the slow movement of Beethoven’s Opus 2, number 2,

to writing down the slow movement of his own cello sonata in F Major, opus 99:

to writing down the slow movement of his own cello sonata in F Major, opus 99:

Beethoven knew Schubert’s Erlkönig. And those sonatas by Dussek. How clever of Beethoven! But that’s not the point. Because this is not history. Given a language — a culture of scripting — texts intersect, overlap. Texts refer, redact.

Schubert’s B-flat-Major Sonata (now D. 960), written in 1828, was published for the first time in 1838. Schumann wrote about the sonata in an article concerning Schubert’s last pieces, confessing: “There was a time when I spoke only reluctantly about Schubert, and only in the night to the trees and the stars… I thought of nothing but him.” Also in ’38, Schumann wrote his opus 16, Kreisleriana. But, this isn’t a matter of history, of real or imagined events.

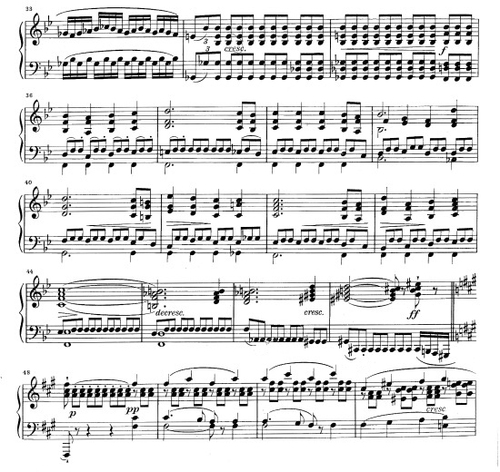

There’s the beginning of Schumann’s text (opus 16, number 2), with its registration, voicing, metric placement with syncopated phrase beginning, and key:

And there’s the beginning of Schubert’s text:

And there’s the beginning of Schubert’s text:

There’s the F-sharp/G-flat ambiguity/trade/unity in Schumann’s text:

And in Schubert’s text, G-flat/F-sharp, here and pervasively in the sonata:

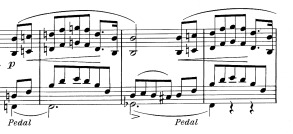

The beautiful/sinister/poignant resolution of the low G-flat is an octave lower in Schubert’s text,

The beautiful/sinister/poignant resolution of the low G-flat is an octave lower in Schubert’s text, than it is in Schumann’s:

than it is in Schumann’s:

genial — and also genius!

How refreshing to read about these ideas! I’ve always respected your approach to the keyboard, Bruce. Now you’ve given me yet another cause for respect. Your insights into the music. Keep up the great work! In the tradition of Charles Rosen, your work provokes me to think and then go back and listen again.