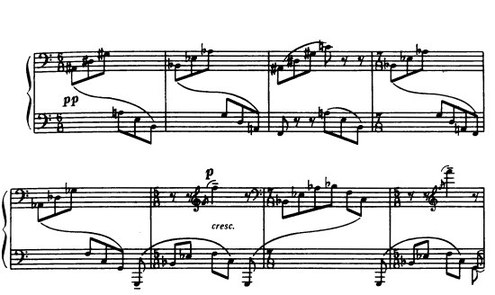

During a master class I gave at the Gilmore Festival, I noticed something in Bartok’s Barcarolla. The piece’s notation mixes measures of 6/8, and 7/8, and 5/8. But in almost every bar there are two big beats. As in lots of folk music, and unscripted music, and perhaps in the actual performance of every kind of music — these beats are not equal in length.

In Bartok’s text, some of the large beats are equal to 3 eighth-notes, others equal 4 eighth-notes, or even 5 eighth-notes. There’s some overlapping. As a long beat (4 eighth-notes in length) is finishing, another long beat might already begin in the pianist’s other hand, as in measure 3.

The use of unequal beats or changing metric-groupings wasn’t new. The early 20th-century’s innovation was the bringing of temporal unequality into European musical notation, into high culture sound representation. Irregular beating and beat organization are pervasive in all music played by humans. (No two beats are created equal!)

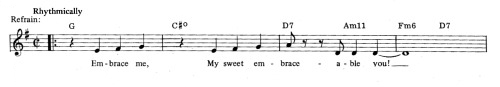

As an encore at the Gilmore’s concluding concert, Kiril Gerstein played an arrangement of “Embraceable You.” On paper, Gershwin’s song looks like it’s in 2/2 time. Yet isn’t a more subtle metric design embedded? At “em-BRACE-a-ble YOU!” in the song’s chorus the music turns (for a moment) into a waltz (3/4), complete with “Viennese” rubato for the oom-pah.

The basic syncopation (I’m counting quarter-notes now: 1, 2-3-4) establishes a pattern of “embraces” through a duple pattern of unequal large beats. Here, at the beginning of the song’s chorus, the pair of groups of gently ascending notes (Em-brace me, my sweet em-brace…), with their syncopated onsets, encode/insinuate the sliding of loving arms… (First the right arm, then the left?)

In balkan music these meters are called “Aksak”, which means “limping” in Turkish. Bartok’s ethnomusicological research greatly influenced his music. One finds the same sort of “meters” throughout the Middle East, North Africa,the Indian sub-continent and western Asia.

I really like that you posted this because I think it hits on an interesting concept of “humanizing rhythm.” I think this can even go all the way back to Mozart (and actually probably even further back to gregorian chant.) In the opening scene Figaro, for example, he adds a few extra measures of instrumental music to accompany the actions happening on stage. Musically, these extra measures don’t quite fit in the form, but they make sense in the opera because of what the humans are doing on stage. This concept develops further with composers like Bartok and Janacek writing rhythms that are more uneven and represent human speech or action patterns. Even early blues composers like Robert Johnson would add weird odd-numbered beats to measures so he could fit all of his lyrics which sound very conversational and less sing-songy. Now a days, there are jazz composers like Jason Moran who literally play along with recordings of human speech. I believe that all of this serves to bring out the musicality in human nature. Beautiful stuff!