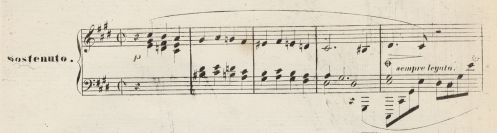

Just before playing a program that began with Chopin’s Opus 45 Prelude, I started to think through the beginning of the music. Backstage in the green room, I had no piano and no copy of the written score — and I couldn’t recall the spacing, the exact arrangement of the notes, of the first chords in the piece.

Just before playing a program that began with Chopin’s Opus 45 Prelude, I started to think through the beginning of the music. Backstage in the green room, I had no piano and no copy of the written score — and I couldn’t recall the spacing, the exact arrangement of the notes, of the first chords in the piece.

Solo pianists who play a lot of music by memory tend to be concerned about forgetting. For many pianists, it’s the main focus of anxiety right before performances. In the midst of playing a lot of memorized pieces, I find that if I perform something with written music, my preconcert anxiety shifts to worry about misplacing the physical paper I’ll need for the concert — forgetting in a different form.

Once after I played John Cage’s Dream (from memory), some audience members were talking to Cage. Someone asked, “What would happen if the pianist got lost?” Almost instantly, and seemingly without thinking it over, Cage blurted out: “That would be wonderful.”

It is why we play from memory: to forget ourselves. Or, to forget that we are reading a script. To give at least the appearance that these events are really happening, that preplanned music is real and alive and subject to unexpected twists, or even to reaching some new and unexpected destination.

Are we deceiving the audience? It was a concern in the 19th Century, as pianists began publicly playing “by heart.” Franz Liszt apparently played music by others from memory, but played his own compositions looking at written notes. (He wanted the listeners to see he was not improvising!)

When we play without notes in front of us, there is some suspension of disbelief. We don’t seem to want our actors carrying around scripts, or to see our politicians reading from teleprompters.

As I moved my hands to the keyboard to begin the Opus 45 Prelude, I hoped that some less conscious part of my memory would take over and produce the right chords — and it did. Now, I travel with copies of the music I’m playing. Even if I never look at them. And I never look just before performing. Or even for days.

Old pieces may get modified by the memory-performer. Simplified, or re-detailed. New fingerings and new enunciations, new voicings or phrase groupings may arise. Sometimes to forget a little is to open the possibility of discovery. Phrases that look square or symmetrical in writing may be more subtly heard and understood in the mind. In the playing of memorized pieces, I sometimes feel that a less-than-excellent sense of pitch or an imperfect command of modern rhythmic sub-division may be advantages — in allowing an uncertainty that yields more expressive contours and a more honest, lived-in, and directional journey in performance.

Perhaps the subject here is not memory but notation? Music in all its dimensions resists capture by something so simple as writing. And in the filtering through our memory of a script, even a well-known, carefully learned script, our foibles may lead us to truth.

“That would be wonderful.” john cage is the man, definitely!

don’t you think it is sometimes more difficult to play with a score just because you are looking at the paper as opposed to the keyboard?

saluti.

Bruce Brubaker responds:

In playing from written music, I do feel a different tactile relationship to the keys. In some chamber pieces that I know fairly well, I make a very conscious effort to keep looking at the score. I want to compare/reconcile what I’m hearing to what I see represented in notation.