In this spring’s auditions, I’ve heard prospective undergraduates perform Beethoven’s “Hammerklavier” Sonata, Schubert’s A-Minor Sonata, D. 845 — and, of course, many offerings of Liszt’s Sonata, Stravinsky’s Three Movements from Petrushka, and Ravel’s Gaspard de la nuit.

These seventeen- or eighteen-year-old pianists are grappling with, or storming through, music that’s considered to be at the pinnacle of musical or virtuoso difficulty.

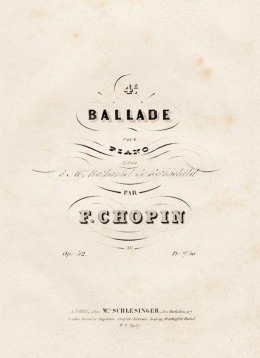

I won’t suggest that these pieces only be played by older musicians. There’s even something to be said for learning very technically demanding repertory at a relatively young age. Coming back later, some solutions to the great obstacles will have been internalized. But, should it seem normal to ambitious high-school students — and their teachers! — for tenth-graders to perform Chopin’s Fourth Ballade and Brahms’s “Paganini” Variations?

I won’t suggest that these pieces only be played by older musicians. There’s even something to be said for learning very technically demanding repertory at a relatively young age. Coming back later, some solutions to the great obstacles will have been internalized. But, should it seem normal to ambitious high-school students — and their teachers! — for tenth-graders to perform Chopin’s Fourth Ballade and Brahms’s “Paganini” Variations?

It’s especially concerning to find that a young master of all of Chopin’s Opus-25 Etudes had no contact with any music by Mozart or Haydn, or that the very first sonata by Beethoven that a bright pianist learned was the composer’s Opus 111.

It’s “repertoire inflation” — that’s what it is! In an attempt to impress, to register on the global scale of piano prodigiousness, our young players are pushed into ever greater difficulties. A graduate student preparing to audition for a doctoral program in a major university was advised not to offer a sonata by Mozart. A faculty member who would evaluate her audition told her not to play the piece. “Too easy,” he said.

What’s next? A ten-year-old performing all of Messiaen’s Vingt Regards, or a high-schooler rattling off Busoni’s Piano Concerto? (Note to certain teacher of international reputation: These are NOT suggestions!)

You may be asking: “What’s the problem?” What’s wrong with some talented junior pianists playing really hard music?

If work is postponed on the basics of music — on what is simple, though difficult to realize, on the fundamental building blocks of more complicated music — then the things that really need to “work” in a piece, in a technique, in art, may never be settled or even considered. It’s not so much that these castles are built on sand, but that their fancy turrets may not signify much of anything. What makes music matter is overlooked.

Yes, it is an inflated world: real estate, life style, and repertoire.

This makes me think of Lipatti. He weighted his capacity/maturity (or something else) carefully w.r.t. Beethoven’s Waldstein.

Easy Mozart? We should ask Brendel and many other established pianists.

One question. Can the faculty at NEC not be influenced by the difficulty of repertoire at auditions? If (extreme) technical difficulty is a factor in deciding admission, students and their teachers would surely, on average, gear to meet the factor. If not, why the NEC student who seeks for a doctoral admission was advised not be play Mozart?

yesyesyesyes……… (like reading ulysses before ….)

The “difficulty” of music played does influence the assessment of performers. But, my sense is that it’s the simplest things that often disclose the most about a musician. The story about the graduate student who was advised not to play music by Mozart, did not involve New England Conservatory. (I didn’t name the school where the student auditioned.)

Your explanation helps a lot. Thanks.

Don’t offer a sonata by Mozart in an audition for a doctoral program in a major university because “it’s too easy?” How can that position even logically be put forth? Are we talking about a hard science like math, or are we talking about the art of music?

Jim

P.S. Nice post by the way.