Some elaborate preparations to long notes in piano music are attempts to mimic the ways singers can begin a sound. The many shadings and extensions of initial consonants may get translated into piano music as multiple short notes, usually notated in small print. Though often marked with a slur, this kind of writing can still be confusing. The articulateness of the keyboard is certainly what’s not wanted — these are compound sounds.

I believe the practice of variously arpeggiating chords, and delineating multiple lines through hesitations and anticipations was pervasive in old music. Let’s welcome back a nuanced “style briseé.” An unbending insistence on “simultaneity” robs us of subtleties of timbre, inflection, and even just of hearing fully all the pitches being played — particularly in dense textures, or in really large rooms.

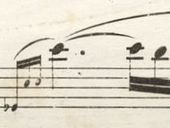

Sometimes, J. S. Bach marks a specific arpeggiation in a keyboard piece:

In American English, we might refer to such a sound as a “rolled chord.” And for me, this is closely related to an opera singer reaching up, through a long rolled Italian “r,” to achieve a sustained high note, and continue the word with an extended vowel…

I always think vocally when I’m playing — I play with a lot of singers — and it comes in particularly with those wide spaces which are not so easy to cross with the voice. Even without rolled chords or preparations I always think of gliding through the wider intervals… long melodic lines fall flat if they sound too effortless.

And like you say, sometimes with Romantic music particularly it makes sense not to follow a slavish sense of simultaneity with all those large chords. You get the feeling of a massed sound, more like an orchestra, or an orchestra with a singer who, in addition to the notes, is also spitting out the consonants and tugging the voice along from one note to the next, slightly ahead of or behind the accompaniment.

Once you do it though it can be tough to reserve it for special moments..

I suppose it all depends on where these little notes are in the phrase–which time period, composer, etc. It can vary, also, based on the performance. For recording, though, it gets trickier because one would like to have their own final say about how to execute these for eternity. But that can change from day to day. True, I agree with you that all of these things should be related to the natural vocal line, but in some instances, it may be an instrumental re-creating we are striving for. On the beat, before the beat, it all depends on the performer and how well he/she delivers their rendition. It must always sound natural and organic.

I would like to offer a different perspective:

We read that Chopin seems to have expected these figurations to be played on the beat, or at least so it appears from some explicit pencil markings in some of his pupils’ scores (supposedly in Chopin’s hand). There are several reasons why we are induced to consider a grace note as a rapid gesture attached to the note that follows: we are all taught that a grace note has to be played more or less quickly; in some cases, the interval between the grace note and the regular-print note would be unreachable (a tenth, for instance); a slur usually connects the two.

What I recently observed is that the grace note in many cases would suit perfectly as the ending of the phrase that precedes it, while the regular-print note determines the beginning of the next (there are several instances in the Nocturnes that come to mind). This would imply that both notes are elegible to align with the bass, contending for the same placement. The reason why Chopin notated it this way is that, in print, this would not always be intelligible: for example, in the instance from the Ballade in A-flat that you illustrated, had Chopin written this as a vertical rolled chord, it might not have been clear that the bottom sixth still belongs to the previous phrase as its resolution, while the higher octave (C-C) determines a new beginning. I think it would all make sense if our idea of synchronization of the two hands weren’t so literal – for instance, if the left-hand bass did not quite come in with either note, but somewhere in the middle of the roll, or as part of a gesture that involves both hands.

In this practice, Chopin was certainly affected by a Baroque performance principle which remained in use throughout the Classical era – in the Andante from Mozart’s Sonata K.533/494, for example.

The level of complexity or subtlety is great.

In Jane Stirling’s copy of the A-flat Ballade, we do see clearly that, at least on one occasion, Chopin wanted to align the first of the small notes with the down-beat bass note. There are “little notes” in 19th-century music that seem to belong with what comes before — look at several instances in Robert Schumann’s Opus 16. And in the pre-recording era, any notions of “simultaneity” must have been quite different from what we experience.

I certainly believe that more “broken style” playing can help us in the realization of keyboard music. And it’s not limited to traditional repertory…

It is also an expressive decision to be made in atonal music. Do you want to project the unitary klang of a chord or, by rolling slightly, the chord as formed by members of a set?

Actually, I have a question rather than a comment.

We have debated this in piano lessons as well as in Conducting classes. I haven’t been able to find a reliable resource that has the information I need about grace notes. Is there one source that you all know that discusses appropriate usage of grace notes across composers, geographical locations and time periods? We covered this information briefly in classes but without verification in text.

Thanks!

~Serena

Bruce Brubaker replies:

Serena there may be a project in there for you! Of course, playing ornaments is very entwined with several aspects of music, music making, and notation. In eighteenth-century music, I believe it’s helpful to consider the function of the note in regard to harmony.