The patterns of stress inform everything. More, less. Less, more. Our languages (our speech) inform our music, our thought, our designs, and concepts — our emotions? I am — iamb! In Western European music, the falling inflection predominates, strong, then weak. That’s the two-part poetic foot, the “trochee.” “Iambs” (weak – strong) are rarer in music and (?) in French, German, Italian (so rare as to need a marking — città). In these languages, rising inflections are rarer? — syncopations. (There are three-part and more-part feet too. And the length of syllables might be considered.)

In music, we frequently associate falling inflection with pitch. A higher note followed by a lower note is often read and performed as: more and then less. More sound, more intensity for the higher pitch, less for the lower pitch. But, if the lower note is longer in duration than the first note, a shift in inflection is probably signified. A short high-note, followed by a longer lower-note is: weak – strong. (C.P.E. Bach tells us, in case there was any doubt in your mind!)

In a master class, a student played the beginning of Maurice Ravel’s “Ondine” from Gaspard de la nuit. There are poems by Aloysius Bertrand with this title. Another student asked the master, “Is there a direct relationship between the poems and the music?” And the master answered, “It’s not specific, just atmosphere …”

In a master class, a student played the beginning of Maurice Ravel’s “Ondine” from Gaspard de la nuit. There are poems by Aloysius Bertrand with this title. Another student asked the master, “Is there a direct relationship between the poems and the music?” And the master answered, “It’s not specific, just atmosphere …”

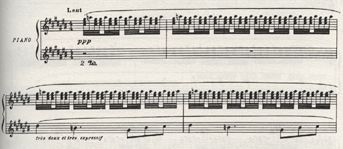

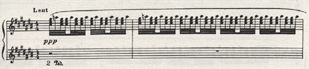

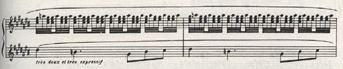

The melodic line begins (second system, in the left hand) with a descending interval, the second note has longer duration. The student was being coached to play the first note louder, with more stress. But, this is a case of “syncopation” — the longer duration of the second note gives it more stress, even though its pitch is lower. (The “slur” shows the whole line is bound together legato.) And, if there was doubt about the emphasis pattern, Bertrand’s poem begins: “Écoute, c’est moi!”

Écoute,………………………………

c’est moi!

Doesn’t it make more sense that she starts singing when the L.H. comes in (first two bars being water music)? If so, then Écoute falls on the descending 3rd, although word stress in French is pretty unpredictable anyway.

Anyway, I can’t imagine wanting the B to be louder than the D# – although it would be nice if the D# could crescendo! I recommend vibrato on that note.

However, I’m sure I’m influenced by how I’ve heard it, and by having heard a teacher sing that interval as “ON-dine.”

I agree–there is a parallel with the poems–in some cases, you can almost say the poem as the music is performed. In the Liszt ‘Sonetto del Petrarca no. 104’, that is a parallel of the music and literary, and one might not recite the Sonnet simultaneously. Ditto for the Chopin Ballades or any other literary inspired musical composition. When I am asked to compose music based on something literary, I hear the literary as a melodic pattern somehow, much in the way lyrics become the song.

Quick follow-up to previous comment. It makes the most sense to me to set the first 7 note of the L.H. to the words, “Écoute! – C’est moi, c’est Ondine…” (Granted, the poem repeats the word ‘Écoute’)

i think this is more of a toss-up. the inflection of the line cannot be deciphered by what he has given to the performer. granted, the second note is longer than the first note. yet, for us to assume that second note gets the “strong” value is quite misleading. let me explain.

simply the line is quarter – dotted quarter – and three eighth. according to your analysis in order for the first note to have the “strong” inflection, the second note should be shorter if not the same length. so let’s, hypothetically make the line as the following: quarter – quarter + eighth rest – and three eighth notes, all under the big slur to insure the legato. so according to the poem it would “C’EST moi” not “c’est MOI”

but i feel like that line is quite jarring. having to see all those 32nd notes and to see the melodic line to have a “rest” in the middle of it would totally destroy seamlessness of the beginning. moreover, it would create havoc to performers’ eyes as they would most certainly will play the two hypothetical quarters together and then start the mini-phrase with the three eighth notes.

so, in a sense the “master” who said the poem is more “atmospheric” has a valid argument here. to depict a fantastic body of water requires constant movement of water (the 32nd note) and non-jarring melodic line to sustain and beautify the stillness of the water and its constant motion. and i can safely say ravel may have thought “C’EST moi” not “c’est MOI”, if he thought of it at all.

i do not know if ravel personally knew of cpe bach’s “art of clavier”, and quite honestly i don’t believe that’s the point. if he knew, he could’ve either followed it or done away with it.

so in a sense both views suffice, i believe.

One has to be careful here: stress, length, and inflection are independent parameters, in language, and (I would say) in music.

The Greek prosodic terms we borrow to speak about stress in English metrical feet (“iamb”, “trochee”, etc.) referred originally to vowel-length, not syllabic stress. In English, the two happen to be highly correlated. In other languages this is not true.

One case is Hungarian, which is tricky to pronounce for English speakers. For example, the word/phrase “Tessék” is a “trochee” with a long unstressed second syllable. Try it!

Many native French speakers I have asked seem to believe that French is devoid of syllabic stress. It is interesting to try to persuade them that there really is stress. Maybe there isn’t, for them.

Perhaps a native French speaker could add a comment about the connection between Bertrand’s words and Ravel’s music.

This is difficult to realize after a measure and a half of brouille upbeats. The three eighth-notes at the end of the measure lead back to the D#. The B seems less convincing.

Enjoyed much Lateiner’s Emperor 3rd mvt. Could you talk Arkiv into a reissue of the entire work, or would Jacob nix it?

And perhaps keyboard music is a particlar case. The inflection of lines in piano music, in which the player mostly controls the onset of individual tones, is different from music made with air or bow. Probably the reason the subtle management of rhythm is of heightened inportance in playing the clavier…

Independent parameters or so-closely linked together as to be inseparable? Perhaps that’s the difference, between music and words?

Of course, you are quite right Marc that our languages (and our native language) shape how we perceive eveything. I know of work that’s been done recently, for example, contrasting the perception of “time” by native speakers of English and Mandarin.

No doubt that Ravel was a master at portraying practically anything in music. What a wonderful and texturally fascinating work.

I am curious about the “perception of time” research (ref?).

Of course all of us perceive time differently in different circumstances. Arguing that language is the causal factor would be extremely tricky. The fact that different languages express the same temporal relations in syntactically different ways can lead to faulty arguments. (“No tense markers on the verb, must be a people with a different sense of time” would be a crass version.)

Streams of sounds are concrete enough that hypotheses are easier to test. I once uttered a stream of sound which an English speaker would be very likely to interpret as “by contrast”. The French person to whom it was addressed, because of the way French structures its syllables, interpreted it as “back undressed”. (!)

There are similar ways to misconstrue musical phrases, I believe. A Bulgarian dance, is not a Ländler, for example.

A somewhat related blog entry can be found here. There are some very interesting experiments with taking a piece of music and systematically moving the beats around. The results are fascinating, though sometimes hard to listen to.

Here is a link to an abstract of Lera Boroditsky’s article, “Does Language Shape Thought?: Mandarin and English Speakers’ Conceptions of Time.”

The abstract is interesting, but seems really to be about metaphor, not about language per se.

That metaphor shapes thought seems a far less lofty claim. Some (e.g. Jaynes) have even claimed that metaphor is thought, though I would not go so far.

[The best example I know of this kind of probing of thought-shaping is John Lawler’s classic, “Time is Money: The anatomy of a metaphor.”]

Metaphors for space and time are deeply embedded in every language. It would be interesting to know how the vertical/horizontal choice for time metaphors is made among languages of the world, and whether the vertical option is rare. Perhaps it emerged from the vertical/horizontal choice about writing. Hard to imagine that Mandarin must use the vertical choice because of something intrinsic to its grammar.

The notion of a sort of “native metaphor” with a persistence akin to “native language” is interesting though.