The simplest things can be the most telling. A very small, simple bit of music reveals everything about a player’s technique, sound — dare I say, soul?

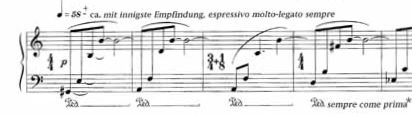

Consider the two-note slur: a group of two notes, frequently a descending step, connected, bound, by a legato phrasing tie (slur). A very basic building block, frequently realized very poorly, even by celebrated, professional executants.

Consider the two-note slur: a group of two notes, frequently a descending step, connected, bound, by a legato phrasing tie (slur). A very basic building block, frequently realized very poorly, even by celebrated, professional executants.

Classical musicians often strongly desire to perform music that is physically hard to play, a virtuoso challenge. Conductors perform Mahler. Pianists are attracted to the intricacies of Ravel. It may be excellent music — and then there’s that opportunity to adroitly cue the third horn!

Haydn’s piano music might be rejected by some of the young virtuosos in my school because it’s too easy. In the conservatory’s series of performances of Haydn’s “complete” piano sonatas, I have felt that some performers regarded this material as beneath them. And it’s a paradox: It’s too easy for them — and far too difficult too!

In the pop world, it may be different. Is Bob Dylan admired for his virtuoso “chops”? Among some rockers and rock critics, there’s a focus on something like “truth” or communicative power that might perplex a lot of classical players. Some classical listeners, teachers, and performers still expect virtuoso pyrotechnics all the time, and feel cheated if they’re not there — in a piece, a program, a recording. “Does he have fingers?”, we ask.

In the pop world, it may be different. Is Bob Dylan admired for his virtuoso “chops”? Among some rockers and rock critics, there’s a focus on something like “truth” or communicative power that might perplex a lot of classical players. Some classical listeners, teachers, and performers still expect virtuoso pyrotechnics all the time, and feel cheated if they’re not there — in a piece, a program, a recording. “Does he have fingers?”, we ask.

Some have extolled the value of physical struggle in artistic communication (Edward Said, Roland Barthes). Cornelius Cardew saw it as a matter of politics or social order. Conventional instrumental virtuosity is a bourgeois acquisition — it takes time to develop, and expert advice to cultivate. Money and “leisure” are necessary to get these skills. And speaking of claviers — well, pianos are expensive.

Some, like Alvin Curran, have sought to notate pieces that can be played by many, a manifesto of inclusion. Gebrauchsmusik?

Alvin Curran: Endangered Species

Perhaps the full syllogism is:

Simple is difficult.

Difficult is easy.

Therefore, simple is not easy.

That’s what the students you refer to seem to have a hard time believing, alas!

It may go too far to say “beneath them”. Everyone has an agenda. Agendas have blind spots. For this reason, teachers ought to challenge students’ agendas, at least from time to time, if they can! (“OK wise guy, what is the sound of one hand clapping? Hah!”)

György Sebők used to ask, “What is difficult?”

Various folks would propose this or that answer.

And then he would say, “No, what is difficult is what you do not know!”

If you do not know how to play a two-note slur, then that is difficult, for you. However it is a category of difficulty that is radically underestimated by students, compared to, say, being able to play “Feux follets” at Richter’s tempo, which is difficult for most people, and therefore not underestimated.

So the difficulty of a two-note slur remains inaudible to them, because it hasn’t even occurred to them that there is a problem to be solved, something to be aware of. Whereas it’s immediately apparent whether one can emulate Richter successfully in Liszt.

In the end, however, conservatories teach the students they accept. Perhaps the fault lies not only in the “stars”, but in ourselves…

Yes, in ourselves, certainly.

And then perhaps it is what Baudrillard describes: music (and much else) disappearing into its own “materiality.” And that leaves us only with simulacra — “substituting signs of the real for the real.”

Forgive me but I really don’t understand this post….

I can’t help but wonder what would constitute an experience of “music disappearing into its own materiality.”

Artur Schnabel said something that sounds superficially similar, but it may well be getting at something completely different: “The conception materializes, and the materialization re-dissolves into conception.”

If one is a performer, one understands the kind of thing he’s alluding to here (although I would say “intention” rather than “conception”).

But I would like to know what Baudrillard is getting at. Unless it is merely that we sometimes mistake the score, i.e. the simulacrum, for the music, i.e. the real. Even in locutions such as, “Did you bring the music.” If so, “simulacrum” would seem a misnomer, since a score is not similar at all to the music whose “sign” it is.

All of this is reminiscent of a debate from the mid-20th century between “Analytic” and “Ordinary Language” philosophers: do words refer (the analytic view), or do we use them to refer (the other folks).

Do our scores “refer”, in some sense, to music, or do we use them to “refer” to, i.e. to play, music. I vote for the latter.

Any true musician will always be looking to push themselves which is why they will always play more difficult pieces. They would soon get bored of playing music if they never tried anything new or found it too “easy”.