Taipei

Yesterday, I was eating the best beef noodles in Taipei with Lun-Yun and his family — genuinely extraordinary food, in the beef, the taste of the wood  used to cook it, the unctuous broth with chopped green pickle mixed in. Before, we had small pieces of pork spareribs cooked in a steamer with rice groats and a hint of spicy pepper — a Taiwanese reading of what I thought was a Shanghai dish, that I used to eat with Jacob Lateiner at the Moon Palace on Broadway. In Taipei, I was eating the noodles but thinking of Boston and New York… Thinking of the two cities I spend most time in, and then of the many cities where I have played music. Thinking of what French wine makers call “terroir.”

used to cook it, the unctuous broth with chopped green pickle mixed in. Before, we had small pieces of pork spareribs cooked in a steamer with rice groats and a hint of spicy pepper — a Taiwanese reading of what I thought was a Shanghai dish, that I used to eat with Jacob Lateiner at the Moon Palace on Broadway. In Taipei, I was eating the noodles but thinking of Boston and New York… Thinking of the two cities I spend most time in, and then of the many cities where I have played music. Thinking of what French wine makers call “terroir.”

After a curiously eccentric play through last week, and with silly bravado, I said to John Davis, “Maybe I’m one of those ‘Boston pianists’ now.” For a long time, the city by the Charles has seemed to me to have its own eccentric taste in pianists. Particular value seems to be placed on intense individuality — versus some easier, more universal style. Perhaps Boston’s local pride of excellent virtuosos constitutes a “school.” One delineation of this geographic pianistic identity appears in the writings of longtime Boston Globe critic Richard Dyer, a discerning listener who has carefully heard a lot of pianists. At times I used to joke that if Richard were asked to name the greatest living pianists he would swiftly answer: “Russell Sherman,  Anthony di Bonaventura, and Dubravka Tomsic” — two scions of the Boston scene and Richard’s favorite “outsider.” Somehow the tastes of Boston, or of that Boston, were rarified in a way I didn’t quite understand, or even completely believe.

Anthony di Bonaventura, and Dubravka Tomsic” — two scions of the Boston scene and Richard’s favorite “outsider.” Somehow the tastes of Boston, or of that Boston, were rarified in a way I didn’t quite understand, or even completely believe.

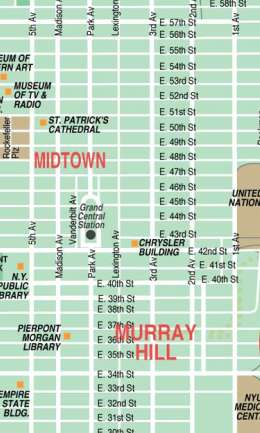

The artistic history of Boston and New York are intertwined and yet discrete. There’s not much physical distance today (different with horses), but the Gestalt of these two places differs alot. As the clichés or truisms go, New York is richer, Boston more European. I have always loved the easy layout of most of Manhattan — its grid of streets and avenues, clear even to someone whose sense of direction concentrates on up and  down. But then, that grid is crass too. Simple and easy, clear, democratic and plain and dull, without whimsy or ambiguity. By contrast, in Cambridge, after a few weeks of coming to the ends of streets with signposts identifying only the cross streets, I asked Patricia Zander about this strange custom. “Oh,” she said, “it’s just that if you don’t already know how to get there, we don’t want you to.” Our friend Silvia mentioned that soon after she relocated to Cambridge she would go to hear the Boston Symphony at Symphony Hall and think, “How shabby the carpet, how dull and dingy the walls.” After a few years, she looked at the very same décor and felt, “How comfortable and reassuring.”

down. But then, that grid is crass too. Simple and easy, clear, democratic and plain and dull, without whimsy or ambiguity. By contrast, in Cambridge, after a few weeks of coming to the ends of streets with signposts identifying only the cross streets, I asked Patricia Zander about this strange custom. “Oh,” she said, “it’s just that if you don’t already know how to get there, we don’t want you to.” Our friend Silvia mentioned that soon after she relocated to Cambridge she would go to hear the Boston Symphony at Symphony Hall and think, “How shabby the carpet, how dull and dingy the walls.” After a few years, she looked at the very same décor and felt, “How comfortable and reassuring.”

One speaks of “terroir” in regard to wine, or other foods. That’s the taste quality imparted by specific soil — the reason that grapes grown in a certain commune taste the way they taste. Perhaps this “terroir” is more important than the underlying grape varietal? We understand that several different grapes could be used in a Pauillac, or that Bernard Michelot blends the wine from grapes grown on different slopes to make his Meursault Perrieres. When we eat a Blue Point, it’s a type of oyster, linked to a very specific place of origin. Is that why the extraordinary Taipei beef noodles can not be made in exactly the same way in New York, or even in Tainan? (When I commented on the exceptional bean milk soup I had for breakfast with my host, one of my table mates said the neighborhood is famous for bean milk!)

In the notes that accompanied the 1965 recordings of the solo piano music of Karlheinz Stockhausen played by Aloys Kontarsky, one could read no specific information about the music. Instead there’s a quite detailed list of all the food and drink consumed by Kontarsky during the recording sessions — half a liter of Vichy water, a veal chop. “You are what you eat”? Or, “You play what you eat”?

Will the Fugu skin I ate at dinner change the way I play Haydn’s music this week? Does the custom of eating small bites of many dishes at the same meal lead to a taste for quick change and surprise? At a basic level, our body chemistry does respond to food and drink. I don’t recommend a double Scotch before your concert, or a turkey sandwich! How far to take this? Some performers are very finicky. Think of Volodya’s Dover sole. Or the pianist who preceded me in India who ate only boiled vegetables. (Eating everything, I eventually got very sick in Delhi. But, I kept on eating and playing anyway.) A middle ground? Exact equations elude. Do we eat saltier food in humid climates, or more fat if we live in northern houses with no central heating? Do we need more beat-affecting rubato as well?

The endurance of “classical” music seems to depend on its portability, and then its mutability. It gets taken over by succeeding generations of musicians from new places — or old places again. After I played sonatas by Haydn in a recital in Paris, a European colleague said, “Only an American could play like that!” I took it as praise. Some European students tell me they come to America to break free from received wisdom about music. Copland and Glass found something essentially American in Paris. After that post-concert remark, I told myself, only a North American could have heard J. S. Bach’s music as Glenn Gould did. Only someone from the New World would have played Bach’s music with the propulsive accentuation of Bill Evans. But then, I’m not entirely sure the comment after my recital was a compliment.

Cognitive psychologists have tried to link the languages people speak to their perceptions of such phenomena as the perceived ascent or descent in successive Shepherd tones. I feel sure that our musical democracy changes the sound of music as well as shifting its syntax and phraseology. How much is too much? That question is answered anew each day and in each place.

In the nineteenth century, the wine grapes of France were threatened by Phylloxera inadvertently introduced from some American vines. (The tiny insects are native to North America.) After many fanciful cures were attempted, almost all French plants were grafted to American roots, resistant to the bugs. So the source of this potentially ruinous pest also brought forth the means to allow European wine making to continue.

In New York, people like spicy food. Does the noise and intense overstimulation of urban life dull our taste buds, dull our perceptions? “In another ten years people will pay ten thousand dollars in cash to be castrated just in order to be affected by something,” Wally Shawn opines in My Dinner With André. Does the New York pianist play faster and louder just to cut through, just to register something?

Often there’s a taste for the “exotic” in big cities (linked to colonialism?). Indian food in London. Chocolate in Belgium. In Paris, Chopin was exotic — writing his transmogrified Polish dances for French ladies — just as Tan Dun is exotic in the West today. Boston still cooks up its local pianistic cuisine. When I play with too many layers of rubato or use too much pedal, I get worried. At the same time, when I rush ahead or New-York-over-articulate a virtuoso passage, that concerns me also. The sheen and polish of New York playing has been my reference for a long time. Joseph Horowitz and others have described the change in playing styles in the New World. Claudio Arrau recalls that an older generation of Germanic pianists was all “Geist.” The mid-twentieth century sense of Werktreue seems implausible today. But we can freely take the S-Bahn from the Zoo to walk along Unter den Linden. And no Moutai for Adorno.