Though inspired by and decorated with 20th century American dance styles, Jean-Christophe Maillot’s 2013 “Choré” for Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo, which had its U.S. premiere at Segerstrom Center in Costa Mesa on Friday, shows integrity only to Maillot’s own sleek neo-classical choreographic voice.

This is not a problem unto itself – Maillot speaks to it in the program notes, citing that Choré’ “does not set out to reproduce (historical) codes. The principle is to reproduce the spirit.” And Maillot’s choreographic vocabulary is pleasingly clean and harmonious. Yet as soon as “Choré”’s ode to the rise and fall of American dance eras proclaims its dark territory – linking modernism’s spiraling dance numbers to America’s easy launch of thermonucleur weapons – the superficial gaze feels unsupportable. What is the point of Maillot indicating devastation and the avant-garde artists and movements that followed — such as Merce Cunningham and Butoh dance theater — if he only appropriates costume design and a few gestures, yet leaves their brave explorations of time or space unpursued?

Penned with French writer Jean Gouaud — also Maillot’s collaborator on “Lac,” the forcibly reshapen “Swan Lake” that Monte-Carlo brought to Segerstrom in 2011 – the five-part “Choré” opens with French narration that seems crucial, as there is a very sad woman (Maude Sabourin) walking in frieze relief, still inconsolable when joined by a partner (Alexis Oliveira). (Translations of Gouaud’s vague, associative narration about the 1920s — eg. “to escape, once more, the fetters of gravity, weight of the world with its cortege of depression and bodies in rags, enduring famine and winter, truck laden high with the grapes of wrath” – appear in italics inside the program’s mock newspaper pamphlet.)

Basically, “Choré” links Depression era dance-marathon desperation to the rise of movie musicals and World War II. After the mushroom cloud, only an anguished abstraction remains, until we arrive in a kind of purgatory – a scene of classical antiquity/fantasia with two weightless, defenseless women floating in suspension before their tender partners. Arising from the sidelines, a fallen couple reanimates (Berenice Coppieters, Lucien Postlewaite) and leads a romping surge into today’s current omnivorous dance environment.

As in much of Maillot’s work, it’s possible to be almost entirely sustained by the company’s dancing power, assisted by impeccable stage and lighting design, while you’re waiting for meaning to unfurl or coalesce. Props are handled exquisitely and Dominique Drillot’s simple set of stacked, open boxes is manipulated to powerful effects throughout. As well, Philippe Guillotel’s costuming of a haunting couple, covered entirely in black, truly reads as a lasting, stubborn shadow, if not the most meaningful one. Much more than in the marathon circles, the ghosts of American popular dance are the figures rising from the Southern slave fields to Broadway and vaudeville.

Maillot’s ease with style appropriation may be a small tit-for-tat. In the first section, the wounded waltzing couples are set ablaze by Postlewaite, who initially appears styled like Gene Kelly in his “An American in Paris” role, where Hollywood employed a thin scrim of French culture as handsome backdrop. The second sequence, featuring the movie-musical number – the most substantive portion of the evening – also contains Franco-American interplay. Guillotel’s dazzling white costume for the Hollywood film director (Aurélien Alberge), is capped by a beret, while the chorus girls wear Breton-striped crop tops and pants, also with berets.

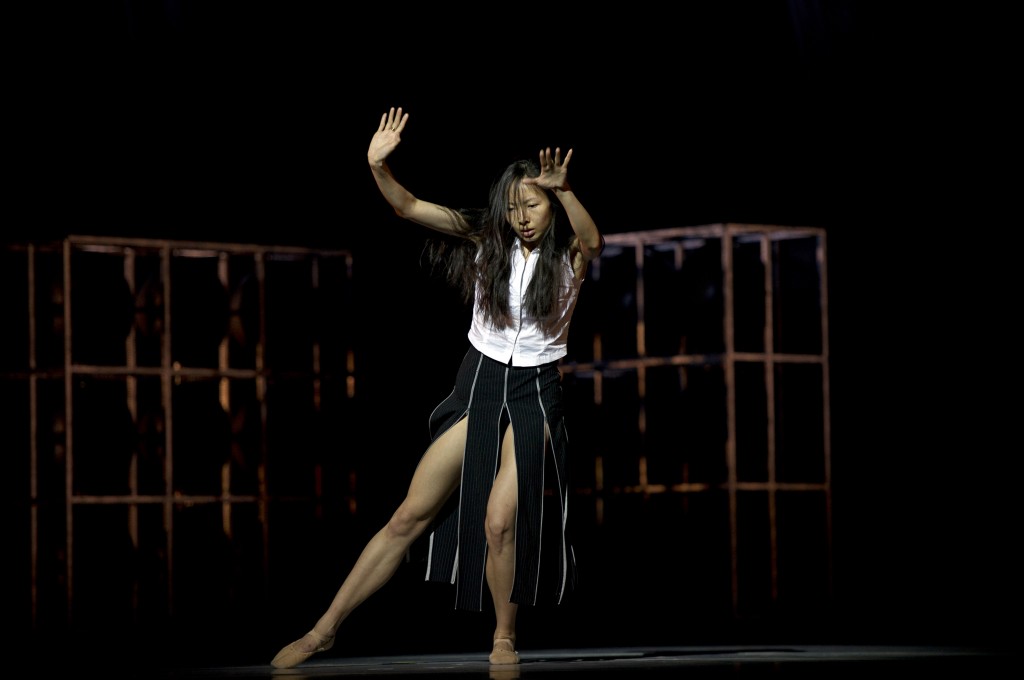

Yet nothing prepares for the scandalous dismissal and dilution of the true tenets of American modern dance in the faux “Cunningham” number, with a desperate female (Mimoza Koike) approximating some of the anguish of Butoh gestures while a gaggle of abstract men in unitards pose and wiggle and twitch. Yet it’s even worse to hear John Cage’s “In a Landscape” – almost Satie-like, so unrepresentative of Cage’s breakthrough experimentalism – used to accompany the portrait of helpless, suspended women (Anjara Ballesteros and Anja Behrend) that features in the final seque. Though it’s kept restrained here, this Botticelli moment is instantly familiar as the kind of jumping off point for today’s acrobatic Cirque shows, which probably was not the intended gesture.

After 75 minutes in all (with no intermission), audiences cheered lengthily for the Monte-Carlo dancers during the curtain calls, though there was unanimous house resistance to a standing ovation. As one audience member described it en route to the parking garage, “What a strange evening. But at least it wasn’t ugly.”

[A version of this review originally ran in the Orange County Register.]