In a rare sprightly moment, Diana Vishneva, as Cinderella, imitates the fashionable dances of the 1930s ball. Photo: N. Razina

Mariinsky Ballet and Orchestra

Los Angeles Music Center

Oct. 8-11, 2015

musiccenter.org/Cinderella

No pumpkin, no fairy godmother, no big dress, no vengeful besting on the dance floor, no heraldic marriage ceremony. If a lacey, pale-blue firehose of royal transformation is not the essence of the Cinderella story, then what is?

Opening Los Angeles’ 2015-2016 Music Center Dance series, Alexei Ratmansky’s “Cinderella,” (2002), created for and presented by the Mariinsky Ballet and Orchestra, delivers a fascinating and challenging revisionist glimpse of fairytale happiness. Stripped of sparkling enchantments, Ratmansky’s three-act version — set in 1930s Stalinist-era Russia — features a strange and unique ballet language, with full arabesques and leaps set alongside odd shapes and phrases that are weirdly hacked and pruned. There is also slow, studied pantomime that seems to bubble up from another time. Variations repeat over and over, as if trapped in a vicious loop. Yet the escalating tension wrought from pitting this seething, stunted choreography against the warm and savory Prokofiev score yields new depth to clichéd characters and storyline.

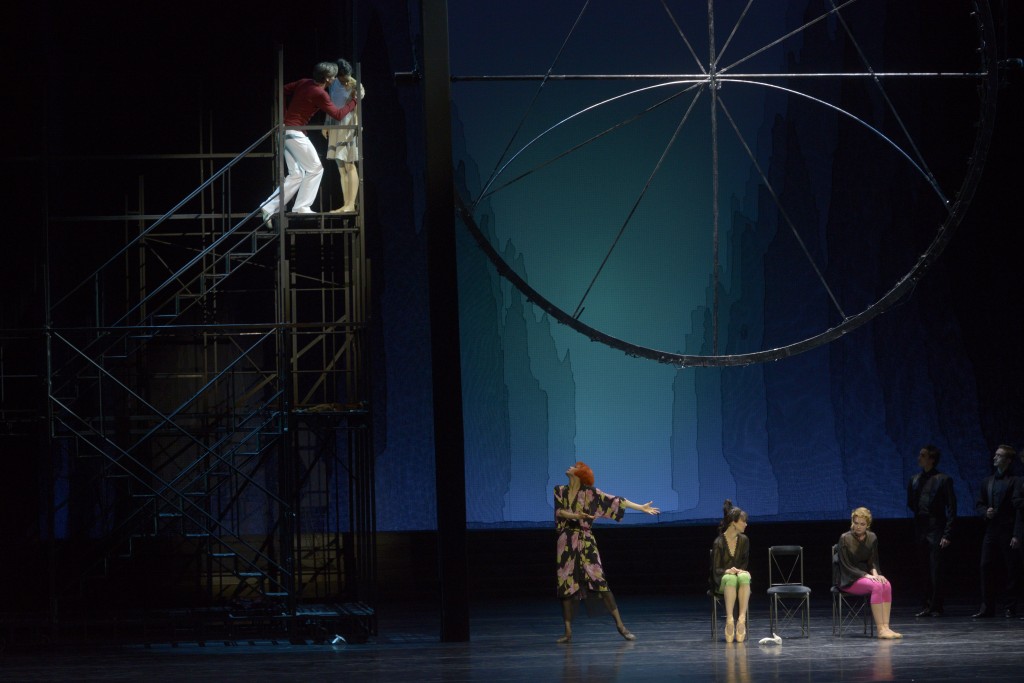

The stark urban setting for Ratmansky’s revisionist “Cinderella” for the Mariinsky Ballet. Photo: V. Baranovsky

On a bare stage bracketed by boxy scaffold staircases designed by Ilya Utkin and Yevgeny Monakhov, Ratmansky’s choreography puts forth an uncompromising vision of stinginess and indolence that is well woven through the bodies and the space. While the music cues classical ballet’s amplitude and reserve, Ratmansky delivers mincing, routinized stepping phrases that convey brass self-preservation and tired detachment. When the unhinged characters in the story (stepmother, stepsisters, a trio of hairdressers) unravel expressively, what they spew out is awkward, twisted, splaying, as if their interior lives had pickled.

Cinderella’s dance with the Prince, where they keep their bodies quite distant from one another (pictured here with Vladimir Shklyarov, from another cast). Photo: V. Baranovsky

In contrast, Cinderella (the inestimable Diana Vishneva) has an innate, preserved loveliness and continuity, even as she’s trapped inside much of the same choreographic phrases as the others. Unlike the layered, colorful outfits everyone else wears, her ‘ball gown’ is but a silky white sheaf, like night clothes for Juliet. Her characterization features slow pantomimes of grief and caretaking for her drunken father and a fairy godmother disguised as a beggar. At the height of her initial meeting the Prince (the glowing Konstantin Zverev), she uncontrollably lunges for the ground, repeating the floor-polishing circles that comprise her home duty. At the climax of their Act III waltz, when tradition would weave the duo together in a variation of soaring embraces, their bodies only just merge for a moment here, a moment there. Instead of delivering transcendent union, her deserved deliverance still elicits unmet love and longing.

Amidst these broken arcs, Sergei Prokofiev’s 1945 score is presented in its totality, and conducted with brio by Gavriel Heine. Look to Prokofiev, Ratmansky seems to be saying, for the full glory here, and the reason for such a caul of darkness. After working in Paris with Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes on “The Prodigal Son” and other ballets, the great Russian composer returned to his homeland in 1938, living through wartime to produce this lilting, stormy ballet score amidst the deprivations and despair of 1945. Yet within three years, his career would be over, and he’d die the same day in 1953 as Stalin, the very man who had confined his artistry and tarnished his name.

Cinderella’s fairy helpers, the male Four Seasons, in formal attire for the ballroom scene with the evil Stepmother. Photo: N. Razina

In this darkened setting, vibrant threads of hope emerge in Ratmansky’s redrawing of Cinderella’s fairy protectors, a male quartet of strange decorative beings called the Four Seasons (Vasily Tkachenko, Alexey Popov, Konstantin Ivkin, Andrey Soloviev). Wearing Markovskaya’s fantastical costumes — including long-sleeved crop tops over tights, face paint, fright wigs and headbands — these four powerful, seductive figures explode on the scene in split leaps and wind-up turns that exude strength and possibility and movement wholeness. Their inspired, independent course feels like a joyful nod to Diaghilevian gender freedom, musicality, and bold color.

To see the Mariinsky perform this work is necessary, for the story mood and movement relies on both the Russian physique and performance style. There’s nothing like the sky-high back attitudes that these long-legged dancers send up, and though it limits their backbends, having legs that consume the majority of their height, the best of them (Vishneva, Ekaterina Ivannikova) have perfected the most achingly delicate way of arching their backs as compensation, like a gorgeous serif at the top of an important letter. When Ratmansky created a version of “Cinderella” for the Australian Ballet in 2013, he was reported to have made significant revisions.

What a tour this was. With “Raymonda” a few weeks prior in Costa Mesa, and then this “Cinderella” in Los Angeles. Their next U.S. visit will be February 23-27 2016 to Washington D.C. with “Raymonda”.