Concert dance is ridiculously evaporative. It enters through your eyes, yet you can’t study it. Repeated music phrases might linger, but live movement performance can barely be held or stored. It’s why people ask to see “Revelations” or “Serenade” again and again, year after year.

And what of the dancemakers — are they struggling with a similar ethereality and content-dissolve as they work behind-the-scenes? What does it take to create a complete phrase of meaningful choreography? Or seal a concert so it leaves a satisfying imprint? And what gets lost in that process?

“Performance,” New York choreographer/dancer Rashaun Mitchell’s compact, 50-minute work, which debuted earlier this year in Boston and played last week at REDCAT in Disney Hall, wrangled amiably with these and other questions. Set amidst a striking visual design — credited to Mitchell, installation artist Ali Naschke-Messing, and lighting designer Davison Scandrett — “Performance” illuminated the delicate and chasmic hopes and outcomes of art-making and art-viewing. (In the program notes, Mitchell cited inspiration from Richard Avedon: “We all perform. It’s what we do for each other all of the time, deliberately or unintentionally. It’s a way of telling about ourselves in the hope of being recognized as what we’d like to be.”)

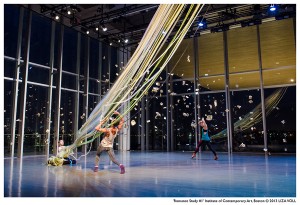

House lights were up and the set was receiving its finishing touches when the piece opened. The overhead catwalks had been lowered so that the dancers could tie tiny dangling reflective pieces to the them, and the floorspace was divvied up into a series of horizontal paths by the hefty metal walkways. The backstage scrim was raised and one could view deep into the distant loading area of the theater. (The photos provided here came from the show at the glass-walled Boston theater; at REDCAT we had only simulated darkness in certain scenes.)

Soon, the first full-body physical gesture of the piece emerged: the cartwheeling figure of Mitchell heading down the long backstage expanse towards the stage, an entrance that evolved from a happy impulse into something complicatedly flat. There was one cartwheel, then another, then a string — it took a while for him to reach center stage. Such a perfect “Look at me!” gesture, repeated and repeated, yet gaining no additive power and not a spec of notice from anyone. He finished, turned face-front, slapped something opaque and metal, like a pie plate, to his face, and moved no more. Other dancers entered and left, continuing to prep the space around him, while he stayed faceless and frozen.

After Silas Reiner taped off marks on the marley floor, with others still working around the catwalks and the frozen form of Mitchell, the stage space took on an increased sense of animation and 3-D depth. By structuring and building viewer anticipation of regions (the marks that dancers would hit on the floor, the horizontal planes of floorspace running wing to wing, the decorated catwalks that would rise upwards into the flyspace), Mitchell seemed to magically pull all of the stage’s colorless cubic feet of air molecules into the composition and set them buzzing.

As all this subtle tinkering came to a close, singer/songwriter Stephin Merritt (Magnetic Fields) appeared downstage, climbing onto a cushion atop the lowered catwalk with his ukulele in hand, dressed in what looked like an upscale pajama set and cap, his legs dangling childlike in the air. Then he strummed a few chords and his improbable bass voice emerged, singing a spry, tuneful ditty (“the world is a disco ball, and we’re little mirrors one and all”), and the full ensemble of dancers — Mitchell, Reiner, Cori Kresge and Hiroki Ichinose — started frolicking joyously together in the band of horizontal space behind Merritt’s catwalk perch.

What a provocation! They skipped in merry, twisting patterns throughout the dance, curling around and with each other, all on one slap-happy note throughout — there were no shifting tones, no clear gestures — so that all the enlivened negative space up there simply sloshed about too. How utterly fascinating, that all that smart preparation segued into weightless frolic. Was it a suggestion of the eventual vacuity of the performance impulse? Did Mitchell like the juxtaposition of the runny blob of dancers against the harsh grid created by the catwalks? (It seemed at times to evoke the whole crazy art of movement notation, where it takes a page of busy markings on a grid to indicate even the simplest element of dance given the myriad possible directions and levels of movement, body parts, duration, spatial relationships, dynamic quality, etc).

In the next phase of the piece, the catwalks rose and disappeared, and the stage lighting kicked in and illumined the display of suspended glittery shards. A second set piece downstage — a cascade of mutant sea-green noodles — became the focus for bubbly narrative play to mimic the lyrics from Merritt’s “Two Mermaids from Barcelona.” (Two mermaids from Barcelona, Spent their evenings playing fado, Crowds would gather just to hear them, Sing of long-lost El Dorado.) Acting out song lyrics is surely Performance Impulse #2, yes? The dancers slowed down here, settling into odalesque profiles and other gestures with capped with serif flourishes.

Merritt’s deft, likeable songs sustained the evening, providing measure and structure against Mitchell’s cumulative assemblage. Yet neither of their wandering, imaginative spirits had the final word in “Performance.” Rather, it was the flyspace, celestial and unpopulated, that let loose a slow-falling rain of outsized bubbles, ready to pop.

PERFORMANCE

Thursday, December 4, 2014 to Sunday, December 7, 2014

Redcat