A funny thing happened when Amelia Rudolph, artistic director of Oakland-based BANDALOOP dance company, launched into the very rare, permit-heavy re-staging of Trisha Brown‘s “Man Walking Down the Side of a Building” (1970) during the Brown Dance Company Retrospective on Friday evening at CAP-UCLA. Just as she crested the edge of the 8-plus story Broad Art Center, in that split second of obtuse-angled suspension before snapping into the 90-degree downward wall-walking path, she heard — amidst a generalized audience gasp — the abrupt words of a young child on the lawn below rising up to meet her. “That’s not dance!” the young girl blurted, and though inaudible to most audience members, the words rose straight up to Rudolph’s ears.

A life-long climber and aerialist dancer, Rudolph inhabited “Man Walking” with a generosity and control simply unavailable to other performers who’ve recently attempted it. It was Rudolph’s first time with a back-oriented cable, and she’d practiced for weeks with rigger Derrick Lindsay. (She usually dances with a cable harnessed to her front mid-section, twisting around and dancing with it.) While the Twitterverse dubbed it “(Wo)Man Walking Down the Side of a Building” in her honor, Rudolph never missed a step, and with permission from the Brown company, added a couple of delicate gestures that made the enrapt viewers downright giddy. Around the halfway mark of her walk, she glanced gently to the right; a few steps further she reached a hand up as if to brush back a piece of hair. Within shouting distance on the sculpture garden lawn, Rodin’s “Walking Man” was caught in his own immortal stride.

This went on all weekend — the creation and displacement and reconfiguration of priceless body-borne Brownian silences and stillnesses, often fittingly (for conceptual art) altered by chance and context. Unbelievable, really, that there were four different site-specific performances, along with the two-chockablock proscenium concerts at Royce Hall. At the Hammer Museum, Brown’s “Floor of the Forest” (1970), featuring two dancers climbing in and out of clothing suspended from a steel-and-rope grid, was performed 3-4x daily by UCLA dance students in the Hammer Courtyard (through April 21), to a soundtrack of voices and plunks coming from the ping-pong games on the terrace above. Dressed so drearily correct, with all our clothing hanging staidly, us human witnesses nearby became audience and performers both.

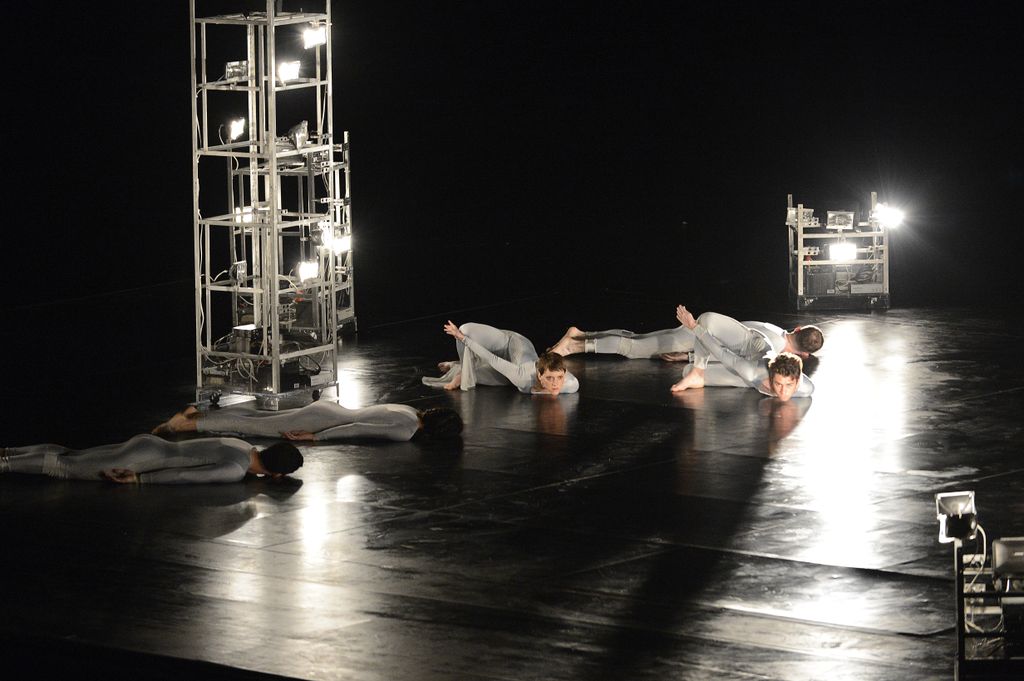

At last Thursday’s outdoor performance of “Astral Converted” (1991), the weekend’s first glimpse of the Brown company’s current iteration of super-dancers, condensation problems on the Sunset Canyon amphitheater stage resulted in a transfigured piece. Though we lost the second half of the work (dancers had arranged to cue one another when the floor surface was too slick to continue, so at a certain midway point the piece suddenly ceased on a dime), the movement quality throughout was more weighted and deeply plunging than usual, plus a half-hour stage-drying prelude drew an effecting new boundary. Waiting on the bleachers for the show to begin, the audience watched for a half hour while black-clad helpers — using hands, feet or brooms — swiped white cloths around the unlit stage. In the distance, a single top-corner window in a darkened dorm glowed yellow, with an additional flickery-blue rectangle from an illuminated computer. Midway through the clean-up, it was announced that Robert Rauschenberg’s eight freestanding lighted towers were going to be switched to aid the work, but this was not “the dance” yet. (If you say so…) When the sleek, silver-clad dancers arrived, and the low groans of John Cage’s score began, the ceremony switched gears and some kind of gathering began. A little bit extraterrestrial, a little spidery, perhaps a summoning of evolved bullfrogs. We were witness — however briefly — to some singular phenomenological visitation.

When she was still choreographing Brown spent little time re-staging past works — especially these amazing site-specific pieces. She felt the maintenance competed with her ability to create new work. This was just the fourth time in 40+ years that “Man Walking” has been performed. Re-stagings of “Roof Piece,” performed twice on Saturday at the Getty Center, have been equally rare. And they’ve never been paired on a single weekend before. And what a pair they make.

With its single dancer on an irreversible trajectory, “Man Walking” was like an arrow shot from Brown to her audience. Her man took off from the sky and bore down towards the gathered mass, finally falling to all fours on the ground at our feet. The clarity and beauty of the extraordinary task delivered a rush of silence, a blanket of hush.

In “Roof Piece,” (1971), featuring 10 dancers signaling to each other across distant rooftops, Brown took the opposite tack: diffusion to the nth degree. Diffusion so extreme that in most iterations — including the Getty last Saturday — you couldn’t glimpse the full picture at once. Seeing the full ‘stage’ on Saturday meant you had to jog in criss-cross patterns around the museum’s plazas and terraces with a map trying to locate all the dancers and pick the best vantage points before the half hour piece concluded.

Though “Roof Piece” was created in downtown New York, it seemed made for the hazy, vertiginous hilltop. While the regular family-heavy Saturday crowd milled around, a scattering of red-clad TBDC dancers appeared like lone, post-season berries dotted against the sunbaked walls and terrace edges. The soundtrack was chance (in my case a burbling multi-layered composition dramatically punctured by a mother repeatedly yelling “Slow down Ayla! Slow down Ayla!” and a tour guide explaining gleefully how every year the Getty gardeners thin out every third leaf from the London Plane trees).

Panic and loneliness and bewilderment of all this sprawl — so recognizable — ruled at first. The flowing red beacons in the distance seemed able to either intensify or ameliorate the sense of entrapment — my choice. So I ran, like a crazy woman, from space to space, dodging marble waterfalls and statues and family clusters, until I found a place, finally, on the South Terrace, where I could see three dancers at the same time, and feel the transmission of movement. To the north, about 30 yards away and 20 feet up, Samuel Wentz was positioned on a stairwell of the South Pavilion sending physical messages to Tara Lorenzen, standing on the plaza right beside me. I was this close to Lorenzen — I could feel the air shifting from her arm swings and hip wiggles. After she initially ‘caught’ a transmission from Wentz, I’d glance southwest, in the low distance. There, about a football field away, the movement would bloom again on Neal Beasley, an oscillating red shape, framed by the Cactus Garden and sealed entirely in silence.

[This piece originally ran with more images and video on KCET’s Artbound site.]