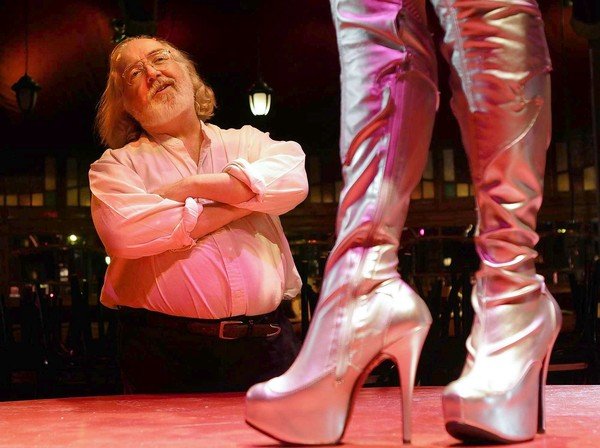

Norm Langille, Artistic Director of Teatro ZinZanni. Photo: Lawrence K. Ho for the Los Angeles Times.

[first published in the L.A. Times]

As the outré Euro-style dinner-theater called Teatro ZinZanni parks its vintage 1910 Belgian spiegeltent on the scrubbed architectural grounds of the Segerstrom Center for the Arts for the next three months, there’s much cooing among the ZinZanni staff about the luxuries of this Costa Mesa locale. “Marble bathrooms,” says associate artistic director Reenie Duff. “It’s a huge deal.”

On a break from retooling scenes for the three-hour vaudeville revue “Love, Dinner & Chaos,” ZinZanni Artistic Director Norm Langill and star improvisational comedian Kevin Kent concur about the lush surroundings. Settling down for an extended run on the lawn beside the Renée and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall affords the Seattle-based organization access to luxe restaurant support from Leatherby’s Café Rouge, state-of-the-art rehearsal rooms, as well as those clean, plumbed bathrooms. Yet Kent — who 15 years ago was working in raunchy burlesque theater and radio with infamous Seattle sex columnist Dan Savage before joining ZinZanni as the cabaret’s deliciously naughty, nougat center — still takes the outsider’s view. “We might be at this beautiful place, but you’ll notice we’re out on the lawn,” he drawls. “Out-side.”

Producer Langill — who looks as though he could be a devilish 1970s Mad magazine illustrator — cracks a crooked smile. “Kevin’s right,” he says. “We’re like a party on the lawn of the estate,” he says. “But it’s an elegant party, with elegant people having a lot of fun.”

It’s not Segerstrom’s first tent. In 2010 “Peter Pan’s” 1,350-seat circus tent resided in the same spot; in comparison ZinZanni’s structure huddles low. (By telephone later, Segerstrom Center Executive Vice President Judy Morr says: “I love tents now. I wish there was always one here.”)

Large-scale fun on the lawn is Langill’s forte. Since 1980, his One Reel production company has produced Seattle’s raucous Bumbershoot arts festival, now North America’s largest urban summer festival. Booking rising talent such as Soundgarden and pairing unlikely acts like Mel Tormé with the Ramones are some of Langill’s fondest memories (“Mel was crying [with joy] when he left the stage”).

Running a supper club sprang instantly and irreversibly to Langill’s mind in 1992 when he encountered his first spiegeltent (Dutch for “mirror tent”) on Los Pampas during the Barcelona Olympics. His initial 1998 show model continues to this day: a three-hour semi-narrative melee featuring top-draw acrobats, aerialists, comics and chanteuses, backed by a keen orchestra, with the players winding amid the crowd, inviting interaction.

In a new show created for Costa Mesa, viewers proceed through a five-course meal designed and created by Leatherby’s chef Ross Pangilinan with Patina founder Joachim Splichal while the artists — with the wait staff’s help — undergo astonishing physical and vocal metamorphoses, with people and plates soaring through the air, wardrobes malfunctioning and a select few audience members enduring chokingly funny participatory escapades. The San Francisco Chronicle’s Steven Winn dubbed the form “a hearty, high-concept diversion” with “captivating entertainment.”

Langill has never aimed for pure historical re-creation — the current show’s theme is supper club meets old-time radio station broadcast — but he does have certain parameters for his creations. Few pop cultural references, little to no technology, lots of physical comedy, plus an attitude that’s racy but not crude coalesce into an aesthetic that Langill calls “pre-Twist.”

“I always imagine it’s sort of like the late-night clubs in Paris,” Kent says. “The doors are closed, it’s after hours, and now the girl is on the swing…. Not only do you leave your cares and troubles behind, but you leave all the other conventions behind,” Kent explains. “You’re kind of coaxed into our reality.”

To achieve that transporting effect, Langill says, “I would not underestimate the tent. There’s a gasp when [people] first walk in. And, boy, I tell you, in performance it helps 100% to have the audience be a little bit off the ground before you start.”

ZinZanni’s commitment to these Deco-era tents — gorged with stained glass, crystal chandeliers and carved mahogany booths — necessitates a flexible, peripatetic life for the organization. Finding locales has been a saga of special ordinances, historical variances and the fine art of building out the tent enough to bring it up to permanent code. In Seattle, it took three major moves until the organization found permitting for a long-term lease from the Seattle Opera House six years ago.

Yet ZinZanni never hit as tough a snag as the sudden displacement from its San Francisco pier home in January, after an 11-year run, to make room for the 2013 America’s Cup. Though Mayor Ed Lee and the Port of San Francisco recently identified a future new home for ZinZanni on the corner of Broadway and Embarcadero, pending approvals, this year’s January-October stretch with a shuttered tent was the lengthiest in company history. “When we had to take it down, it made me cry,” said venue manager Heidi Echtenkamp. “When I saw it up again [in Costa Mesa], I was like, ‘Yes! She’s alive!'”

With this particular ZinZanni tent, which seats 285, the dismantlings and resurrections are impeccable — the Belgian owners of the tent, the Klessen family, fly over to erect it — as well as symbolic. “Our tent was actually boxed and buried under a bridge during World War II to escape destruction from the Nazis,” says managing director Susan Outlaw. “Because it was a gathering place and gathering halls were destroyed.” Less than a dozen original spiegeltents tents survive worldwide; Zinzanni’s two tents are the only ones on the West Coast.

Initially drawing more of a fringe crowd, ZinZanni’s reported $18-million annual business today attracts bachelor parties, cruise ship crowds and families. (Langill suggests kids be 8 or older — “the age when you can actually talk to your kid.”) Supper clubs are just genuinely relaxing, he explains. “People are free to talk with one another, they can get up and go to the bathroom any time they want, they can do something more than just clap and laugh.” Langill also cites the factor of intimacy with the players. “When a performer is this close to you, you can tell whether they’re really enjoying the situation and they really want to play with you.”

Of the 90 players in ZinZanni’s rotation, eight stalwart acts carry the Costa Mesa show: emcee Joel Salom, an Australian comic, acrobat and juggler; the German duo known as Die Maiers, billed as “high-flying buffoons”; Austrian singer-comic Manuela Horn, playing a yodeling dominatrix; Ukrainian contortionist Vita Radionova; Les Petits Frères, a French trio known as “the floating act”; blues singer Duffy Bishop; soprano Juliana Rambaldi; and Kent. Musical backing is provided by a tight four-piece orchestra.

Kent’s antics get at the heart of the show. Making a salad on a man’s head, recruiting a man to play his mike stand, dressing a timid spectator in women’s clothes, Kent can make miracles happen with the most reluctant, unlikely patrons. “I can always tell by the man’s napkin if he’s going to go with me,” Kent explains. “No matter what their face is saying, no matter what words they’re saying, no matter what their wife is doing — if the napkin is coming off the lap and going on the table, I’m in.”