[The Los Angeles Times originally ran this review.]

[The Los Angeles Times originally ran this review.]

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, touring for the first time under new artistic director Robert Battle, delivered a heady, reverberating concoction of pieces — including the company premiere of Paul Taylor’s Baroque pure-dance classic “Arden Court” (1981) and the California premiere of hip-hop choreographer Rennie Harris’ “Home” (2011) — on the first of three distinct repertory programs playing through Sunday at Costa Mesa’s Segerstrom Center for the Arts.

A variety of movement techniques and thematic echoes made for a rare, unflagging mixed bill — one of the first in recent memory that didn’t ask Ailey’s masterpiece closer, “Revelations,” to rouse the audience from programming that hammers with just too much energy, nobility and muscle and not enough subtle challenge.

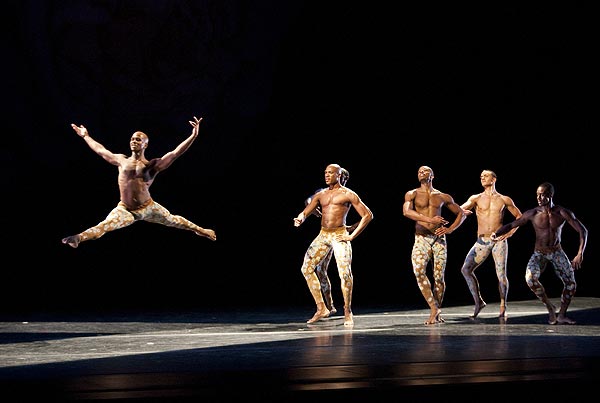

Stylistic range has always been a tenet of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater; even when founding choreographer Alvin Ailey was alive he commissioned work from other artists. But nothing of late has put these dancers to the test like the simple lyricism of “Arden Court,” one of the great confections by Taylor, the 20th century’s most slyly crafty pioneering choreographers, set to William Boyce symphonic movements. Under a massive pink rose, a wave of six bare-chested men flood the space with lunging Martha Graham-like runs (heads darting, arms rising and blossoming overhead), giving way to grand allegro spinning jumps and tumbles, all unfolding in unexpected patterns that ebb and circle and collapse elegantly in on themselves.

Battle — who took over the company’s reins in July — cast the troupe’s most balletic dancers (Kirven James Boyd, Antonio Douthit, Samuel Lee Roberts are standouts, as are Glenn Allen Sims and Rachael McLaren in a playful duet), and all the lines are perfectly clean. Yet there’s a certain stickiness and muscularity to the dancers’ phrasing, no matter how tenderly the shapes and steps are being delivered. Ailey’s choreographic version of sustained movement (a still, balanced center punctuated by delicate percussive accents) is just not the same as pure, unending flow, and the dancers are reaching into unknown territory here. Neither Ailey, nor Taylor, has ever looked like this before, and though it’s not yet satisfying, big kudos to Battle for such a chewy treat.

Harris’ “Home,” inspired by writings about living with HIV, is propelled by a hip-hop salsa lexicon that proves these dancers have no rhythmic limits. Guest artist Matthew Rushing (he’s primarily Ailey’s rehearsal director now) carries the crew through an anguished, ecstatic testimony to dance and community with clear “Revelations” references (group huddles, moments of fanning, clapping and jumping in place, a single skyward arm punctuating the group scenes, a “gospel house” score). The women are particularly bedazzling here (Renee Robinson, Linda Celeste Sims, Hope Boykin, Akua Noni Parker, Alicia Graf Mack, and newcomers Kelly Robotham and Belen Estrada). They keep things focused when the weirdly flat, presentational stage arrangement and smoky-dance-club lighting dims the work’s pulse. With “Takademe” (1999), one can add Battle’s name to the list of brilliant solo choreographers such as Isadora Duncan, Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn who found inspiration in music visualization and East Indian culture, and styled it exquisitely. Using Kathak dance gestures, Battle’s virtuosic choreography (performed by showstopper Boyd) perfectly illumines a charismatic Indian drone performance by Sheila Chandra.

For the last few years, citing the work’s anniversary, or former artistic director Judith Jamison’s last company tour, “Revelations” (1960) has closed every Ailey program, and though there’s no announced “reason” this time, it feels right during this time of company transition. Some highly effecting company members left this year (Clifton Brown, Jamar Roberts), making for a total of nine brand new dancers. That’s a lot of change for a company, especially one that audiences treat like their best, exalted family.

Photo: Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Times. From left, Glenn Allen Sims, Antonio Douthit, Samuel Lee Roberts (obstructed), Jermaine Terry, Michael Francis McBride and Kirven James Boyd.