[this article originally ran on Crosscut]

In 1943, Norman Rockwell — then America’s most popular artist, with regular Saturday Evening Post covers, annual Boy Scout calendars, plus scores of major U.S. advertising campaigns — was tapped by the Office of War Information to create a series of posters titled “The Four Freedoms.” Based on the central content of President Roosevelt’s January 1941 State of the Union Address, the posters were recognizably Rockwellian but featured more serene and dignified characters than his usual paintings.

The four gentle, homey compositions — advocating Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear — were published as Saturday Evening Post covers in February-March 1943 to a great public swoon. Yet according to Rockwell biographer Laura Claridge, the entire Writers Division of the Office of War Information (OWI) resigned en masse to protest the selection of Rockwell over Ben Shahn (and other more socially conscious artists), citing in particular Rockwell’s commercial ties to the Coca-Cola company, one of whose executives had been the arbiter in the decision to choose Rockwell.

In anger, Claridge wrote, Shahn and the OWI writers collaborated on a poster featuring Lady Liberty holding a Coke can with the slogan: “The War that Refreshes — the Four Delicious Freedoms!”

Yet the OWI directors were not disappointed. When the four Rockwell posters went on tour to 16 cities across the country in 1943, in a tour co-sponsored by the Saturday Evening Post, they drew an attendance of 1,222,000 people and raised an unbelievable $130 million in poster sales for U.S. war bonds.

Today, the Americana illustrations and paintings of Norman Rockwell continue to hustle — and deliver — on this country’s behalf. According to figures released by Mary Melius, director of traveling exhibitions at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Mass., tours of Rockwell imagery and process are boosting attendance at regional museums throughout North America. An average of 55,000 visitors are attending each three-month stop of the major touring show, “American Chronicles,” featuring paintings spanning Rockwell’s 50-year career. Museums are “very, very pleased” with the show’s draw, said Melius, and it is currently scheduled out through June 2013.

In Tacoma, where “American Chronicles: The Art of Norman Rockwell” is showing at Tacoma Art Museum (TAM) through the end of May, attendance has been similarly booming. Even during a weekday, you’ll find numerous families and other humming klatches circling back and forth through the exhibit — and weekends can be downright crowded. Though she declined to release specific numbers yet, TAM’s director of marketing and communication, Melissa Traver, said, “We are trending at a 30 percent increase over projected attendance.”

Open since late February, “American Chronicles” (aka “Rockwell’s Rockwells”) features 44 paintings that the artist either kept or bought back for his own collection, plus 323 original Saturday Evening Post covers, copies of the Four Freedoms posters, a short, looping biographical film, and an in-depth display of Rockwell’s working process. Notes, staged photos of the characters, charcoal sketches, correspondence, and final oils illustrate his efforts on one late-era painting: the unusually somber and dramatic “Southern Justice ( Murder in Mississippi),” Rockwell’s 1965 oil capturing the moment of slaughter of three civil-rights workers, commissioned to accompany an article by Charles Morgan, Jr., published in Look magazine.

The exhibit does an admirable job of broadly fleshing out the fullness of Rockwell’s sensibility — from his early desire to entertain and please (and make money) to his yearning in later years to address issues of prejudice and civil rights. In the same corner of the exhibit you’ll find “If Your Wisdom Teeth Could Talk They’d Say, ‘Use Colgate’s,” a 1924 painting for a Colgate dental cream advertisement, and “The Problem We All Live With,” Rockwell’s 1963 depiction of desegregation battles for Look magazine, featuring a Ruby Bridges-type character bravely marching to school in a perfect white dress.

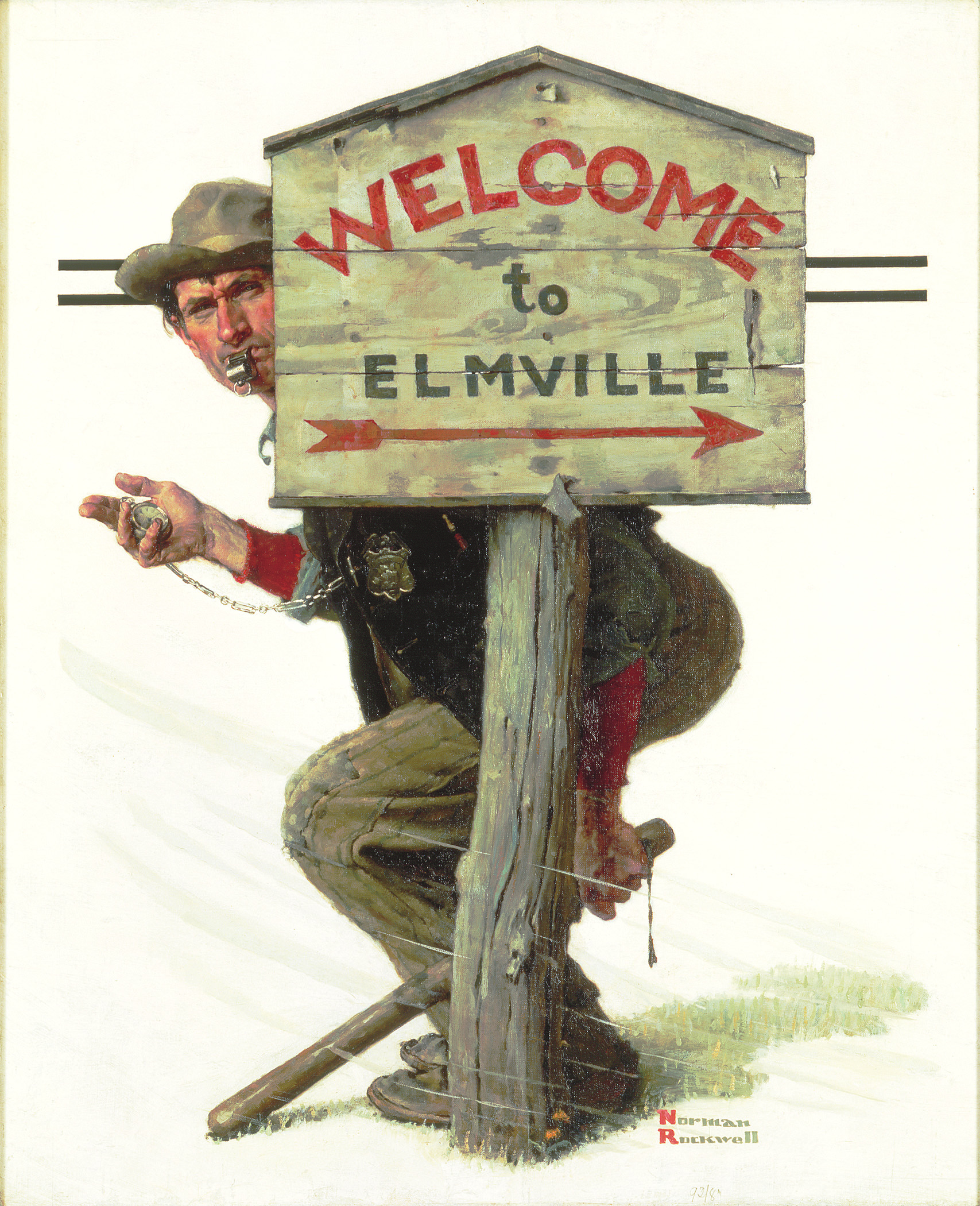

Unsurprisingly, “American Chronicles” serves as a colorful resurrection and recasting of the plucky denizens associated with faded Rockwell merchandise: the boys fleeing with their clothes from an illicit swim (“No Swimming,” 1921); the adventures of a scrappy pig-tailed girl (“Day in the Life of a Little Girl,” 1952); the bug-eyed kid who’s just found a Santa suit in his parents’ bureau (“The Discovery,” 1956). Seen in gallery format, in oil at their original size (each approximately 2×3 feet to 3×4 feet), these overexposed scenes glow anew with color and narrative energy.

Though he was known to overwork his paintings (throughout his life he painted compulsively, seven days a week, nine hours a day), Rockwell’s cataloguing of detail in these oil portraits exudes pure good humor when seen live, especially en masse. Proceeding through the show, the bad odors of the nationalistic agenda that attached to Rockwell’s work are replaced by a sense of one man’s individual, genuine appreciation of and attention to all sorts of shadings of the human heart. As John Updike put it, “Description expresses love,” and that sentiment is palpable when staring into Rockwell’s painted leather shoes, floppy tongues protruding, or a set of fresh comb marks traced in a young boy’s greased hair.

The show provides an experience not unlike roaming the idealized family attic. Interesting, amusing artifacts of historic eras (Post covers that move from two-color printing to four-color process) sit alongside G-rated memorabilia (the turquoise-verdigris of an old Chevy) and it all cements a story of familial love and social bonds. What could be better?

Yet an afternoon with Rockwell images also accumulates a lot of exaggerated body parts and poses, and I felt unexpectedly battered, in the end, by all the kids’ jutting elbows and knees, the old men’s lurching, squatting gestures, and all the beaming, super-responsive faces. According to biographer Claridge, Rockwell had been instructed to exaggerate facial expressions in his works so that readers could grasp his paintings’ meaning “within two seconds.” But why must the bodies be so acute, too?

Only on very rare occasions does Rockwell paint a physical environment for his scenes, which adds to the looming feel of the characters. It’s all people and props, carefully staged for an easy read, unmetered from place, making the only essential site in the exhibit Rockwell’s own stool, which may be the source of that gangly physical intensity. The artist spoke of never shedding the childhood physical feeling of being “pigeon-toed, narrow shouldered — a lump,” and in an interesting anecdote about painting a portrait of actor Gary Cooper on one trip to Hollywood, Rockwell explains how the act of seeing Cooper brought him an intensified sense of his own body. “When I looked at him,” he explained, “I actually felt my narrow shoulder and puny arms.”

Perhaps that’s part of the success of the greatest work on view, “Checkers (1928),” an oil on canvas painted to accompany a story in Ladies Home Journal featuring a downhearted, white-faced clown playing cards with fellow circus people. Allowed to amplify the depressed, clownish feeling that he was otherwise always fighting against, Rockwell blends pathos and beauty into high art in this beautiful work. The small dog at the bottom of the scene (which Rockwell admitted he often added to a painting to carry the emotion of the moment) has been put to sleep, in a clown collar, in this portrait — he is not needed. Seated on a stool in a shadowed, sunlit corner of a circus tent, Checkers the lanky clown with a painted smile has just made a shrewd, engaging move.