Pistachios, raw

Nothing goes without saying, and I have said and written many times that my father, Harry Weinstein, was crucial to my cooking and eating life. If you have browsed this blog over the last decade you might recall his salami and eggs, or my watching him delicately prize open and slide down steamers in the clam bar at Brooklyn’s long-gone shore-stadium, Lundy’s. He took his food seriously, with concentration I’ve rarely seen elsewhere.

To be sure, my mother, Edythe, cooked more food for us than Harry did: it was her task and responsibility, made more taxing because her first son, “Jeffrey Ian” (as she called me when angry), was diabetic at so young an age.

Although she said she was French, raised Catholic and indeed converted to marry Jewish Harry, Edythe managed to master Southern Italian: a two-day ragu, theatrical overstuffed artichokes that looked like inverted flared skirts, and a painstaking braciole: beaten-thin slices of beef (flank steak, I think) spread with who knows what blend of cheese, herbs, crumbs rolled into tubes, tied, baked in orange juice, sweet Marsala, olive oil and blanketed in mom’s tomato sauce. We pronounced them bra-zhawl, and our Midwood, Brooklyn kitchen on those red-letter nights smelled so much better than the result tasted, which was puzzling to a child, when aroma trounced flavor.

Edythe also assembled a clear, golden chicken soup, usually with celery, carrots, onions and noodles added at the last minute, wide bowls of it placed in front of us before she lit the Friday-night candle with a Diamond kitchen match and paper napkin on her head. Brother Leslie and I would giggle, even though we worried that her comical tichel could catch fire.

Mom had told us, in hushed confidence, that she had an aunt who died when her gauzy frock caught a fireplace ember.

“Did you see it happen?” I asked, but didn’t get an answer. No name, place, date, merely a scary, cautionary story .

Dad was forever (and intentionally) late, and we were told to sip our Sabbath soup before everything got cold.

I cannot recreate that silken broth. Here’s what I wrote a few years back after trying to match it many rueful times:

I probably could have duplicated my mom’s when I was 8. Can’t talk about skill here, I had none. Cooking, when you’re young, is watching a chore that’s a dance, before you can dance.

Edythe learned Jewish chicken soup how? From Mrs. Simon Kander’s Settlement Cook Book, the 1938 edition, bought after she moved in with Kiev-born Harry, before they married. Our Settlement was properly stained (which recipes?) when I paged through it: a sickish boy excused from school, set to do homework on a kitchen stool, eyeing the white-enamel stove.

For this recipe, you started by choosing “an old hen.” Dad told us that as a boy, he learned to chop the heads off squawking chickens at a Catskill farm the Weinsteins visited some summers. His father, Aaron, died before I was born; mother Mary when I was 10. Distant and caring at the same time, grandma fried us pumpkin seeds every autumn.

Who were Edythe’s parents?

You can read my last post, which explains a recent genealogical discovery. Not one of her family was French, spoke French, cooked French, as she often claimed with natural conviction. Her Irish-English-Scottish mom, Anna Greenwood, early on skipped out on her husband, my grandfather, Vincenzo Ciraldo.

He was born September 28, 1889 in a Sicilian village called Bronte and came to Ellis Island in 1906 or ’07, a stalwart teen. He stayed with family or former neighbors, can’t tell, in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn — near that later restaurant, Lundy’s, my father and I shared.

Bronte, on the slopes of belching Mt. Etna, was and still is known for one thing: world-famous pistachios — as far as food can be a star. Marketers call the small biannual hoard “green gold.”

So, I can repeat Harry’s kosher Hebrew National frittata (wait, he added milk!) and make a stab at Edythe’s sweet, stolid red sauce, which I don’t much like now.

“Mom, how did you learn Italian food?”

“Neighbors.”

Her given name was Edith, Edith Ciraldo. She never once said that name to me.

Why would I, a skittish Jew moored in Italian foodways by accident or preference, envision and dream about what my newfound Sicilian grandfather may have eaten before he boarded a Hamburg liner at Napoli?

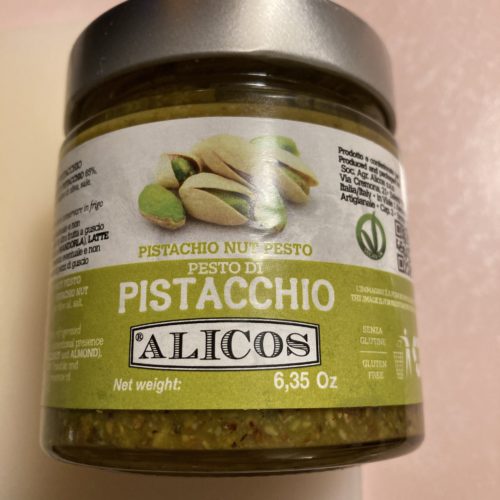

Eataly is a chain of food stores established in Torino that has imports you can’t get elsewhere in the U.S., so I visited the local one to score some Bronte product. Luckily, I bumped into a buyer, who plucked three things from his shelves: a cloying “Cream of Pistachio” that mimics Nutella, dessert wafers with no I’m-special nuttiness, and a tiny jar, Pesto di Pistacchio (at left), of chopped, maybe-Bronte nuts, nearby olive oil, black pepper, salt. No basil or cheese.

Food historians make professional hay from specific quandaries: who cooked what, when, why. Still, their task is statistical, unless a particular medieval feast, served by serfs, made its way onto royal parchment and a goblet-hoisting narrative could be constructed.

But what about you, adolescent grandfather? Did you spit out those god-awful green things that look like bugs, reject their chewy chalkiness the same way I threw up when forced to eat Kraft macaroni and cheese? Had you been compelled to strip and gather nuts in the deadening heat?

Nonetheless, I planned an Etna supper, one young Vinny may have eaten, to be served in our late-19th century East Village tenement apartment, bathtub in the kitchen, a place my escaping relative might have slept in with a half-dozen others. What would he have been offered, have scrounged, or himself put together before or after he left his volcanic home?

Wish I’d seen his face then, or later on, whether he smiled after he swallowed.

The winter greenmarket had glowing finocchio the size of thumbs, so I bought a handful, found promising oranges, black olives, red onion and dressed them with unfiltered olive oil from a Northern California grove. I’d made a similar salad for Thanksgiving dinners, but now it accompanied an enigmatic celebration.

All I had to do was find past pasta, and I looked with my new, quarter-Italian eyes and chose not dried and Sicilian, but what was fresh: pappardelle, a Tuscan ribbon. Boiled the pile, spooned on most of the pesto jar, added pecorino as I stirred in drips of pasta water to meld a sauce, sprinkled on fresh chopped mint, offering Catanian red-pepper paste for those who needed awakening.

My personal, yearning meal was simple. Pistachio shards bloomed in the oil and wet heat; guests were puzzled and perhaps pleased. I should admit that I later tried a more elaborate 19th-century possibility, using raw green pistachios from California that I blanched, ground, and stirred energetically with fresh ricotta from Aleva Dairy in Manhattan’s Little Italy (“America’s Oldest Cheese Shop Established 1892”). The fatty, grassy cheese stuck to my palate when I sampled, but its easy pistachio sauce, with rosemary and cliche parsley, turned sodden, almost gluey. All of this is to say grandson didn’t like it.

Failure can be corrected, but imaginary food comes with no second chance. Ancient Mesopotamians awoke to bread and beer, yet we can’t ascertain how their breakfast actually felt, tasted, or what it meant to any of these remote, sympathetic beings, even with records and reports. That’s the nature, the doubt, of retrospective cooking and eating.

Without his writing or voice, I can never know exactly what one special Sicilian put on his plate, ate, or thought when he did. To my regret, I will have to live with that.

One of your best essays ever, Jeff. Are blog posts eligible for those Best Food Writing Annuals I used to buy reflexively? If so, I think this one should be submitted. (Of course, it’s about more than “just” food, although food is never “just anything” in MY book! That’s one of the reasons this piece is so GREAT!)

Thanks so much! I never want to throw these pieces out there, but maybe I should.

What a twisting, turning voyage, Jeff! My grandmother, who could competently cook little did make a bolognese (just called spaghetti sauce around our house) that was deliciously quite similar to the real thing–in my probably faulty memory. How did this Catholic, Irish? woman married to a full blooded Catholic German (Sommerhauser) learn how to do this? Especially in Anaconda, Mont., where I doubt there were any Italians for hundreds of mile–certainly none she was not likely to turn her nose up at. I’ll never know. Cheers,

Thanks so much for this mirror comment. Yes, we’ll never know. Cheers to you!

This is a very charming essay! Shouldn’t these pieces be compiled in a book? Just sayin’….

I hear the word “book” and blanch (not like a vegetable, I hope). You’re not the first to say that. But it’s probably because a book about any Edith might have some appeal.

Wish I had read this beautiful, resonant essay earlier on this grey, blustery, cold Chiicago day. What a lovely essay and smooth mix of food, memoir, history, insight. Thank you for writing it; i committed a few cooking ideas to memory and smiled when i read “….as I stirred in drips of pasta water to meld a sauce” (a technique you showed me last September).. In my childhood home, we had a stained copy of the Settlement Cook Book, (not sure which edition) resting in a kitchen drawer on top of an aged Joy of Cooking by Irma Rombauer..

Yes, we had a “Joy” too. I read them like bibles. Thanks!

Throughly engaging and wonderful. So glad I saw this.

Tricia

Thanks so much, Tricia! Hope all is well.