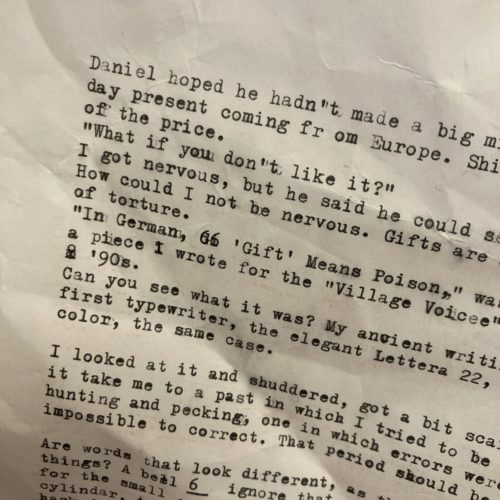

The lede reads: “Daniel hoped he hadn’t made a big mistake. It was a birth day present coming fr om Europe. Shipping was a big part of the price.”

I’m copying from the page above, so it’s all [sic].

The package arrived from the U.K. weeks before my Virgo birthday.

” ‘What if you don’t like it?’ I got nervous, but he said he could send it back.”

Sure, I could retype the whole first page I wrote on my gift on my MacBook, or scan and copy a doc that would come close. But any accuracy would be challenged by age: mine and the fractured planet of typefaces, fingers, sounds.

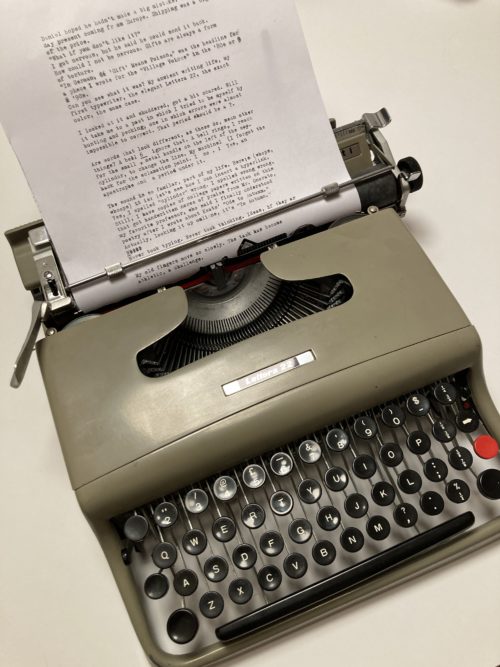

My boyfriend and partner, Daniel Felsenthal, chose for me my first typewriter, an Olivetti Lettera 22. Not the same object with my fingerprints on it, which may be rotting in a toxic landfill or be the exact gift to someone else. In case you’re curious, the 22 is considered sleek and clever, in the design collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

It could also be in the Museum of Torture.

I was excited and ripped open the box: identical model, identical color, in the identical dirty-brown case.

That sentence is almost the same as the one I manually typed right after I replaced the original dried ribbon it came with. Changing the ribbon, my fingertips borrowed the ink, just like it rubbed off when I was 16, or later, reading the Wednesday Voice or Sunday Times arts section that I got on Wednesday — black and later color. Washing dishes in a tenement sink got them almost clean. A person who types in the past is never completely clean.

I was off to college and they said I needed a typewriter. My dad walked into my brother’s and my bedroom (Harry rarely did that) when I was alone and handed me this thing with handles. Dad was a car dealer and bookie who had “friends” who found him stuff.

“What is this?”

“It’s special.”

He got it, as they said then, “off the trucks.”

In September, 1964, he drove me from Howard Beach, Queens, to Waltham, Mass., my crummy Beatles clothes and untried Olivetti in the borrowed white-Thunderbird trunk.

A few years before, I was handed a bulky Japanese “portable” radio, my first no-label alien object, which enabled me to listen to the Democratic nominating convention late in bed, lights out. Adlai went down this time, and I went to sleep modern and sniffling.

My likely used Lettera 22 was portable. I hope I thanked my father, grateful.

Now, when I lift it, I can’t imagine I carried it anywhere: it weighs more than three Airs.

I never took typing, so hunted and pecked. You had to cobble keys to make an ! : apostrophe, reverse, and period under it. (Perhaps there was less printed enthusiasm then.) A bell rang when one reached the end of the line, like a trolley. Then I moved my hand to swing back the carriage. Clang, clang, clang. Typing was an endless Judy movie, dialogue to come.

An aside: In the ’80s I wrote a piece for the Village Voice with this headline: “In German, Gift Means “Poison,” typed on an early newspaper computer system called Atex. Not long before, I had filed a restaurant review of a novel but dreary Mexican place in the East Village and asked my readers if they could tell it was composed on a computer, the first digital Voice article ever.

Lame joke, though it rippled.

“If a union steward like you uses the new keyboard,” my boss said, “maybe others would give up legal pads or Remingtons and save time.”

Should I have stopped? I liked the quiet, the screen. It was happening anyway.

That’s what I thought then, sweating in my seat.

The gift is a vision, but a challenge. When I glance at it, in the case or out, I’m flushed with simultaneous gratitude and apprehension. My lifelong deadline monster, waiting for opportunity, grasps my throat.

Can I type an assignment on time? I know I did in college: why Lolita makes so much highway sense, how Keats’ “Ode To Autumn” layers sounds and smells in a way that a sad, swoony teen could tear up over. Professor Onorato returned that paper, having written, in dark, curly script, “you finally understand.” He was my first and true college crush.

Not long ago, digging around, I discovered these same college papers, water-stained but legible, typed on onionskin, which may have been on sale at the Brandeis bookstore or I thought was classy.

Why not retype them on my new machine in a wasteful exercise? But who would pen the comments…

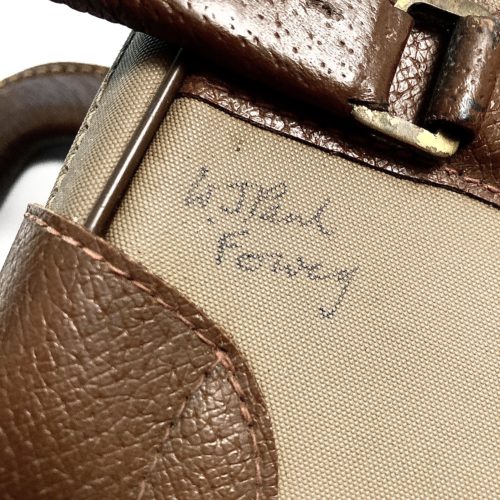

Cleaning the case, I saw this signature: W.J. Paul. That’s the name of the author of Modern Irish Poets, published in 1894. Fowey is a small town and port in south Cornwall, England, with a high school, Fowey River Academy. If you, W.J. Paul, happen to read this, I’d be so pleased if you got in touch.

Can an object miss its owner?

Typing now is odd because I have arthritic fingers in my right hand, which I’ve written about (on my Mac) in a recent post. Striking old keys seems like a prescribed exercise to strengthen me, as if writing itself could not.

I’ll give it a try.

Birthday gifts are difficult. Daniel found the perfect gift and the perfect recipient who could appreciate the gift on so many levels. One writer to another writer. One creative man to another. I read this piece, and, not willing to let it end, i reread it. It got me thinking of the medium blue Smith Corona manual that i took to Urbana, Illinois in 1967 and that was stolen from my apartment by a burglar who came in through my bedroom window and left footprints on my pillow. The burglar also swiped aluminum cigar holders that my father filled with dimes and gave me for spending money. This piece is spectacularly resonant and beautiful composed, by a man whose words ring no matter how he puts them “out there.”

What a great present! And belated happy birthday to you!