Each time I get a post from the site Memorie di Angelina (Easy. Authentic. Italian.) I assume it includes a recipe I want to cook. Author Frank Fariello’s nonna Angelina left Campania in the 1920s and settled in The Bronx on Arthur Avenue. Through her Sunday dinners, Angelina took the boy on an eating and cooking path that his later years working in Rome and around the home country made inevitable. Yet Fariello’s kitchen voice whispers in welcome modesty, which is a paradoxical result of direct engagement and confidence.

In my past lives — sure, you may laugh — I was either a child in one of Italy’s hilly regions or in some section of middle India. My flavor dreams, which still thrill and sadden me, provide no route for easy escape. Smells rarely match images, sleeping or awake, but I hear seeds crackle, pots bang, with cinematic singing or chanting from some cloudy outside. Now, when I fix Italian or Indian food, oil or ghee shimmering, I must be careful not to slip away and lose touch with my own stove.

This post, “Zuppa di cicerchie (Grass Pea Soup),” pictures a bowl of tomatoey beans with grill-marked cuts of Italian bread on the rim, ready to scoop. I’d never heard of cicerchie, or grass pea, so I read it was “an ancient pulse” — nice vampiric phrase — and that the recipe is similar to those from Umbria and places not too far.

The hard part is finding the beans. New York’s Italo-market Eataly doesn’t carry them; Amazon does. I went through the inviting text and cooked the otherwise ordinary recipe in my head, but when I got to the end-note, I stopped:

The cicerchia is a kind of primitive chickpea, which it vaguely resembles, although it has a rather earthier taste. Said to have originated in prehistoric times in the Balkans, it was quite popular in Italy in the Middle Ages. The hearty, drought-resistant plant was a source of badly needed nutrition in times of famine. After falling out of favor in modern times due to the health risks—excess consumption can lead to lathyrism—the cicerchia has recently seen a revival in interest, most commonly for soups like this one or paired with pasta.

Words to learn, my fifth-grade English teacher would be proud. What the hell is lathyrism, and if my boyfriend asks for seconds (he always does), will he come down with it?

A Caesar’s cold yolk or tainted romaine can make you really sick. Canned tuna kills, as it did a lonely secretary, I read in the New York Herald Tribune when I was the same age as little Frank. And what about that rouged wild mushroom standing alone?

Spoilage, sewage or the wrong rarity is one thing, an imported rustic bean in an online soup is another. Were I to serve this, what am I doing to myself and hopeful guests? Is menu transparency called for? No, loved ones, we’re not doing a butch blowfish number at tonight’s table, but here’s the deal …

Those were my thoughts before I knew what lathyrism was. Too much of anything can make you sick, a commonplace. But you never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough — an English-major quote I cited to drink and smoke my way out of college.

Here’s a narrative spoiler: I made the chewy, somewhat nutty soup, ate it, boyfriend ate it, and we’re fine, so far. The big clock is ticking, as usual. Always wondered if my last word would be delicious!

It’s the sorriest of realities, but what can help can kill. Cicerchia, also called grass pea and chickling vetch in English, almorta in Castilian Spanish, sprouts in dry sand and thrives where most things die. The plant’s delicate blue or white flowers give cheer, and the fast-farmed bean is so nutritious it could . . .

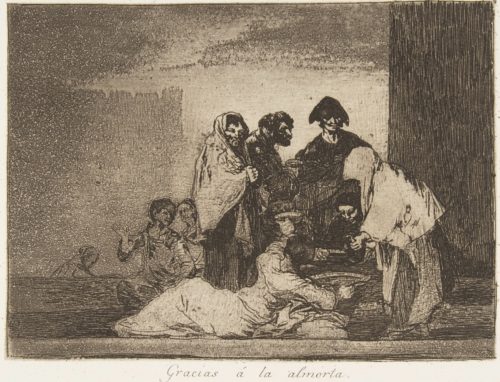

Plate 51 from Goya’s “The Disasters of War,” Gracias á la almorta, shows the wretched and starving eating from a cauldron. Why is the woman in white on the ground? Her legs are dead, paralyzed. This porridge, gachas manchegas, is all the food they have during wartime, made of beans that will grow even in a Goya hellscape. Eat them and them alone for days, months, and they will nourish and save you. But you’ll possibly collapse forever: lathyrism.

Malaria is a famous tropical scourge, but lathryism is a shadow disease, barely acknowledged, that has crippled the poorest of Spain and now those of the arid Indian subcontinent, along with a similar wretched disease, konzo, that fells sub-Saharan Africans who subsist on bitter cassava root, which weathers even fire. Buttocks begin to wither, then legs fail, paralyzed. The cause is the same: neurotoxins. The lathyrism one, β-oxalyl-L-α,β-diaminopropionic acid or ODAP, would be diluted harmless by a varied diet or even enough water to soak and cook the beans in, because ODAP leaches out.

Neither calamity is taken seriously where it counts, according to a 2012 report by PLOS: Neglected Tropical Diseases: “The two diseases are not considered reportable by the World Health Organization (WHO) and only estimated numbers can be found.”

The poorest, illiterate and powerless drop to the ground. Because the cheap grass pea is used as livestock forage, genetic research has focused on making sure that pigs and sheep who eat the dangerous beans don’t totter and shrivel before they become money. Nothing has worked so far, because the same studies show that the toxin helps the pea plant survive — even better as climate worsens.

Oh, perhaps I should mention a citation in Wikipedia that I’ve tried to confirm, though it seems so awfully likely: “During WWII, on the order of Colonel I. Murgescu, commandant of the Vapniarka concentration camp in Transnistria [between Moldova and Ukraine], the detainees — most of them Jews — were fed nearly exclusively with fodder pea. Consequently, they became ill from lathyrism.”

A lathyrism “epidemic” hit post-civil war Spain in 1941-43. Thousands wrecked by Franco’s vicious war had only almorta flour to boil or bake into wafers, and they would never walk again, Fascist or free.

Care for supper? Let’s say that The New York Times cooking site, or ever-present this chef or that, posted our soup with the same alarming footnote. Sure, I’ll provide tiny tweaks to Mr. Fariello’s recipe. His isn’t the only one for these sock-and-buskin beans: dozens abound, some because of Italy’s thoughtful and resolute Slow Food movement, which supports cicerchie and sees longterm value in buried treasure.

Will you take my dare and cook? I think it’s safe. Yet the challenge is of another sort, to recognize that all foods we purchase have pain invested in every bite. Ingredients and the way they come to us are the results of patience, labor, love, and the causes of war, slavery, death.

I’m doing something I’ve never done, which is copying the recipe and suggesting adjustments in italics, which is merely a typeface way of changing voice.

Zuppa di cicerchie

Serves 4-6 (2 will devour)

For the initial simmering:

250g (8 oz) dried cicerchie

A clove or two of garlic, left whole

A bay leaf

SaltFor the soup:

1-2 cloves of garlic, finely chopped (double the garlic, as always)

A sprig of rosemary (and a few sage leaves if you like)

200-250g (7-8 oz) canned tomatoes, finely chopped

Salt and pepper

Olive oilFor finishing the soup:

Rounds of toasted bread

Olive oilDirections:

Soak the cicerchie overnight. (Scaredy-cats, cover with as much water as possible and change it as often as you see fit. Make sure thirsty pets don’t get at it.)Drain and put them in a large pot with water to cover (a few inches at least), together with a pinch of salt and a bay leaf (or two). Simmer until tender (count on almost two hours and add water as necessary).

Meanwhile, in a heavy saucepan, Dutch oven or terra-cotta pot, gently sauté the garlic and rosemary (and sage leaves if you’re using them, or whatever else you have, or nothing) for a minute or two, until the garlic is just golden. Then add the chopped tomato and let it simmer for about 5 minutes, until it has thickened slightly. Remove the garlic and herbs. (Never figured out how to remove chopped garlic and not necessary if it isn’t overdone.)

When the cicerchie are tender, drain them (saving the bean broth) and add them to the pot, mixing well. Let them simmer for a few minutes to soak up the flavor of the tomato base. Then add a ladleful or so of the pot liquor, enough to cover, season generously with salt and pepper, and continue simmering for another 10-15 minutes or so, stirring from time to time (if this makes you nervous, add plain water, but you’ve soaked the bad stuff out of the beans already). Just before serving, taste and adjust for seasoning.

If you like a thicker soup … crush some of the cicerchie against the side of the pot with a wooden spoon (yes, do). Conversely, add more pot liquor if things get too thick for your taste.”

Soup’s on. Again, thanks to Memorie di Angelina. I must ask, though, what we’ll be thinking as spoons are lifted, beyond pleasure, if we hear past voices, or future silence, as distant neighbors struggle.

Wonderful, as usual, Jeff! I LOVE your essays. They feed me!

Uh, thanks anyway, but I’ve just made a delicious Moroccan red lentil soup and I think that’ll hold me.

I didn’t know *any* of this stuff, though. I remember hearing you could suffer from too much spinach (oxalic acid) or carrots (or maybe it just turns you orange?). When I was still quite young, my brother did a study of the genetic marker for the syndrome that makes fava beans highly toxic to some people. It kind of terrified me I think.

The Goya thing is amazing

I’m fascinated by the fear of being made ill by food—I mean, more than by the ways that food can poison us, which are interesting enough in themselves. And I’m saying that as a person whose only serious hospital stay was due to food poisoning. I always wonder if what scares us about some foods is close to what makes us crave others.