I wrote this in October, 2008, for the online “Obit Magazine,” which called itself ” ‘The New Yorker’ of Death.” It’s been two decades since his murder.

None of us can control how we’re remembered, though we may try to live in ways that minimize the dancing on our graves. Yet a special place should be made for those who are memorialized not for how they lived, but how they died. Those singular victims of war, accident, or crime may become famous, even important. But their daily voices, their quirks and smiles, their plain ambitions and ordinary loves risk being overwhelmed by the drama of their end. Celebrated so publicly, the private person we also mean to mourn might disappear.

On Oct. 6, 1998, college student Matthew Shepard (who preferred to be called Matt) was taken by two young men from a bar. He was driven to a windswept plain, pistol-whipped and robbed, tied tightly to a wooden fence, tortured, and left under the stars to die – which he did on Oct. 12, five days after his bloody, insensate body was gathered up and brought to a hospital. The bicyclist who found Shepard in the morning thought the sagging form was a scarecrow.

Many readers will know exactly where this happened: in Laramie, Wyoming, population 26,000. I visited friends there decades ago and was surprised at how small it was. When the University of Wyoming football team had a home game, the whole town emptied into the stadium, its streets deserted.

It may seem odd, but this awful story still has currency, and for one reason. Matt Shepard was out. He wore black patent-leather shoes where cowboy boots were de rigueur. He was a diminutive, polite, sometimes brash gay man who was viciously murdered at age 21, not by “outsiders,” as shocked townspeople said in a way that implied some local absence of cruelty, but by two regular guys almost everyone knew.

Ten years ago, someone’s death made major news because that someone was gay.

Until then, the occasional murder of men and women because they were “that way” went mostly unnoticed, so few could have predicted the immediate response of almost universal revulsion to Shepard’s beating. Comedian Ellen DeGeneres, whose coming out the year before had placed her face on magazine covers everywhere, said in an agitated interview that “I can’t stop crying, this is what I was trying to stop.” President Bill Clinton, clearly moved, urged the passage of a hate-crimes bill that would include the likes of Matt.

That bill, now awkwardly called the Matthew Shepard National Law Enforcement Hate Crimes Prevention Act, is stalled because George W. Bush vowed to veto it. Barack Obama supports the legislation; John McCain previously voted against it. Wyoming is one of just five states that have no law pertinent to any category of hate.

Two years after the rapid trials and life-sentence convictions of Russell Arthur Henderson and Aaron James McKinney, a well-regarded play called The Laramie Project by Moisés Kaufman told the story of Shepard’s death through interviews with 200 of those involved. Laramie Project has been performed in thousands of community theaters and schools – and sometimes challenged by those who disdain a portrayal of gay anything, even a murder.

The play and trial records indicate that neither the jury nor most anyone else believed the defendants’ “gay panic defense” – that Shepard came on to them sexually and caused them to lose control – or their subsequent claim that this was merely a robbery that went wrong. Defense attorneys had long considered the gay-panic justification a slam-dunk; something was changing.

Shepard’s mother, Judy, soon became her son’s civic champion by founding the Matthew Shepard Foundation, dedicated both to remembering his passing and challenging the sort of hatred that led to his death. She spoke at a foundation fundraiser in Cheyenne, 50 miles from Laramie, and some online comments appended to newspaper coverage of her visit denied any gay component to the murder and blamed Mom for riding its coattails. Others attacked anti-hate laws as unnecessary left-wing ploys: “Freedom of choice is the right to hate,” one read. A few respondents, though, hoped that their beloved “live and let live” Wyoming could repair its damaged reputation.

“A tough business,” one of The Laramie Project’s characters say, “to be gay in cowboy country.” Wyoming resident Annie Proulx agrees: Her story “Brokeback Mountain,” upon which the movie is based, has a local man murdered almost certainly for being gay. It was published before, not after, Shepard was killed.

Not all antigay murders are the same, and looked at closely, each killing, like each death, has something unique about it. Earlier this year, Lawrence King, an assertively femme and frequently bullied eighth-grader, was shot in the head in computer lab by California classmate Brandon McInerney and later died. Did 14-year-old Brandon snap because Larry had said he was cute? Should absent parents or a negligent school share the blame? And is the beardless killer a victim too – of commonplace, run-of-the-mill homophobia?

Yet statistics also tell particular stories. The Anti-Violence Project, based in New York, states that at least 21 gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender people in the U.S. were killed last year as a result of hate-related violence, up from 10 in 2006. (The increase may be due to better reporting, the project says.) That’s almost two dozen Matts, remembered, we hope, by someone. Thousands more last year were harassed, beaten up, stabbed; teens were kicked out by parents, taunted at school, humiliated at church. Every gay man I know has at least one hate or fear tale stuck somewhere in his satchel, and I have mine. For example, when I was in Laramie so long ago, I was carefully told not to stroll its charming streets alone.

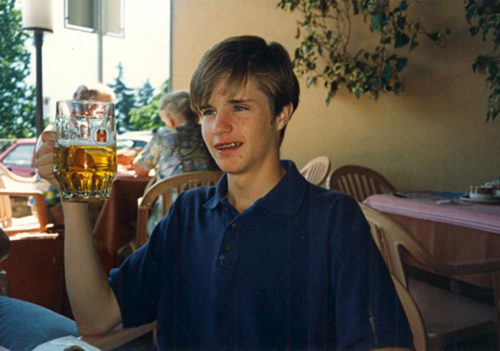

So how should we think of Matthew Shepard on the 10th anniversary of his death? He wasn’t a martyr, as some have said, because martyrs are supposed to choose their sorry fates. Instead, Matt appeared to be a somewhat brave young man, idealistic, ready to join the struggling gay and lesbian group on campus, wanting to have some impact on the world. Yes, he had a callow, self-centered side, which we learn from the more personal interviews we’ve read. But there’s no full, detailed account of who Matt really was. He hadn’t achieved much. He left impressions.

On Sept. 27, the University of Wyoming dedicated a small bench with a plaque that reads: “Matthew Wayne Shepard Dec. 1, 1976-Oct. 12, 1998. Beloved son, brother, and friend. He continues to make a difference. Peace be with him and all who sit here.”

A little late? Perhaps. And if I were there, I wouldn’t sit, but take myself for a nice, long walk all over town.

Thank you once again, Jeff, for keeping our history alive.