[contextly_auto_sidebar]

We have so many ways nowadays to discover how boeuf en daube is pronounced without having to tap a French shoulder, human or beef. Raise your hands, readers, if you know what novel lists this dish as an ingredient. I read that book, probably unwillingly, more than 50,000 meals ago — I counted — and fastened on the scene at the end of the first part that gathers characters to look at and smell their spotlit dinner without any obvious hunger or lust of appetite.

That was in the early ’70s, when Bloomsbury rebloomed. Coincidentally, Virginia Woolf’s entree invaded this shore at that time via Upper West Side academics, Woody Allen dining rooms in the same nabe, and the perplexing bourgeois dominance of Julia Child.

I was a student at some of those tables on which Danish salad bowls sat, carefully cured, yet I don’t remember any particular boeuf en daube, just the mood and company around them: garrulous, competitive, immersed in a vicious wartime moment yet yearning for an elegant, licentious past. Being young, I wanted to throw rocks, if only to remind us how Virginia Woolf died, though I’m sure that someone right next to me would have smirked and cited Hamlet‘s Ophelia.

In decades after I’ve put together stews and bourguignons that have risen and sunk, but the literary daube escaped me. It’s not all that different from its peers, yet, how can I say this, the “daube in my head” had too many words attached.

For example, writers about food continue to make fun of To the Lighthouse‘s Mrs. Ramsay because of her statement, based on a hostess’s nervous need to please, that her maid (who was also the cook) brought the treasure to the table at just the right time: “To keep it waiting was out of the question.”

For example, writers about food continue to make fun of To the Lighthouse‘s Mrs. Ramsay because of her statement, based on a hostess’s nervous need to please, that her maid (who was also the cook) brought the treasure to the table at just the right time: “To keep it waiting was out of the question.”

Anyone who knows is supposed to know otherwise. Then they make fun of the author for thinking the same thing, too dim to divorce Woolf from her fiction. Meanwhile, our meat is getting cold.

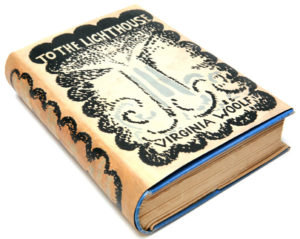

(First edition is at left above, published in 1927 by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press, with a woodcut cover by Vanessa Bell, the author’s sister.)

X X X

Poor Mrs. Ramsay — no first name — made me think about something that’s bothered me for ages. How many times have we read or heard that a soup or stew will “get better” if it sits musing for one day, two days, three? The idea goes that in time, arrogant ingredients learn to mingle. Everyone says yes to this commonplace, but in my experience, sometimes a dish gets better, sometimes it doesn’t.

Novels may get better as we stew about them. Others fall apart.

Nothing improves if it were never good in the first place. As for the rest, I would do a blind test. But, after thinking about it, that wouldn’t work because I’d have to cook a recipe and make the exact same one a few days later to see if the first version surpasses the last.

But here’s the question. Can any eating be “the same”? (Philosophers play musical chairs with the lit types at my Bloomsbury table.) Restaurants, by definition, try to persuade us that menu items are clones, but we know that’s not the case. The other night I ordered the usual steamed victim at my local lobsteria, but this time its flesh was gnarly and tough, nothing like the muscle I have stripped from its plump, sweet forebears. I was also worried about an election in Alabama. That sort of thing will affect a meal.

But the problem has more to do with the power of what we consider momentary. Anyone who has lived through the coexistence of Existentialism and takeout Szechuan understands that nothing tastes the same twice, which happy fact throws the ordinary program of restaurant reviewing into the trash, along with the evening’s greasy cartons. If something as trivial as conversation can put you off your food, how can clear and solid evaluation rise to the surface? It may, but only in a collective way, skimmed from the top like bubbly scum by a supposedly careful cook.

X X X

“Oh, the whole building smells good!”

He said this coming through the door, and what a welcome. All it took was vadouvan in butter and olive oil, doing what it does with onion and a pencil of Cubanelle pepper. No party gathered to eat, merely the two of us.

And in fact, I cooked the daube above and below a few days before, thinking guests would just appear.

Ingredients for recipes are like strangers at a table: wine works its charm with both. I’m going into food mode now, explaining that “daube” comes from a bulbous terracotta pot called a daubière, which heats and moistens in a bottom-up way. Pots often name the foods they cook.

You won’t need a clay pot, and I don’t have one. But the problem is the boeuf, which I consider a celebration choice, an increasingly rare addition to my table. There’s this weird reversal that has become romantic, because a daube fastens on the parts of the animal that were once cheap and considered troublesome: the sinewy shin (you know where your shin is), blade, chuck, or round — which is what I used, because it was available. The result, which, if I may say, was supernal, would have been better with shin, because I could have cooked it a whole day, or even two. We find ourselves in a world of all-day, not hour- or minute-, cooking.

Do you meditate? Here, the beef is meditating.

X X X

I’m going to write the method and put a list of ingredients at the end. That matches the way a daube cooks.

Because I worked from various recipes and an automatic twitch that knits them together, I first placed a really big bowl on the counter. That gives a cook confidence.

I put about four pounds of round cut in chunks into the bowl. Smashed a bulb of garlic, removed the mummy skins and added to the pot with two big bay leaves, leaves from a few sprigs of thyme, four thick, peeled carrots and three or four celery stalks cut into eating lengths, three sliced onions, salt, black pepper, a bottle of red wine.

Look, it can’t be plonk, but it needn’t be the wine you want to drink with the result. I used an elaborate-sounding Portuguese blend, grapey and tannic.

“A whole bottle?” he asked. “Isn’t that expensive?”

Squish the meat with your hands. Imagine something you’d like to do to someone else. Then put in the fridge overnight. Wash those hands.

Decide what you want to cook this in, a big Frenchy casserole to go into the oven or a slow cooker. Slice about half a pound of mushrooms or more; fry the same weight of thick bacon until fat’s rendered but before it crisps. Find a friend to pit half a pound of the best black olives you can scare up or assertive olives of any color.

If using the oven, preheat to 250 degrees. Cooking will take five or six hours, so plan ahead. Increase temp if you have less time, but not to over 350.

Cut cooked bacon into half-inches. Find a can of whole tomatoes, a tin of anchovies, and have a few tablespoons of capers on hand.

The present question is whether to flour and saute the beef for its cliche fond.

No need.

Another choice to make: drain the solids, saving the marinade, and layer them, or dump the wet mess unsorted into the casserole or cooker, along with bacon pieces and whole tomatoes squished up?

If you layer, first goes some beef, bacon, then tomatoes and vegetables, then beef and bacon again, vegetables. Pour in all the marinade, adding water or wine to just below the top of the ingredients.

Cook on low in slow cooker or covered in the oven. You needn’t stir, but you may wish to, for the pleasure of it.

After three hours, chop anchovies and capers with oil from the tin and swigs of olive oil and wine vinegar. Add and stir. Cook for another two hours, then test. Leave the cover off if gravy drips watery, which in a slow cooker is not easy to do unless you turn the heat up.

There will be a point at which a transformation happens that should be famous. The mass darkens and amalgamates. Its initial siren smell collapses to sighing aroma. Oil rises and glistens, olives bobbing. You think you’re making it better by watching and stirring, but all is done.

- 4 lbs. chuck, round, blade, or shin

- 4 thick carrots, peeled and cut to 2-inch or so lengths

- 3 or 4 stalks celery, cut to at least an inch

- A teaspoon or two of fresh thyme leaves or a pinch of dried

- Three or four onions, any kind but sweet, peeled and sliced thin

- Salt, black pepper

- 1 bulb garlic

- 1/2 pound portobello or button mushrooms, whichever looks good

- 1/2 pound thick bacon

- 28 oz. can or more whole red tomatoes

- 1 bottle or more red wine

- 1/2 pound pitted olives, not canned

- 1 tin or small bottle of anchovy fillets

- 2 tablespoons capers

- olive oil, wine vinegar

- chopped parsley

It wants rice tonight, noodles or new potatoes, plus a baptism of parsley, to approach its bright, silent goal.

I’d like that right now, with noodles, please!

Even before I choose a peaceful time in which to savor this much-awaited Out There, I would like to place its title right up there with another of Jeff’s indellible recipes for a savory read: his Village Voice restaurant review

headed “Basque Mitzvah.”