[contextly_auto_sidebar]

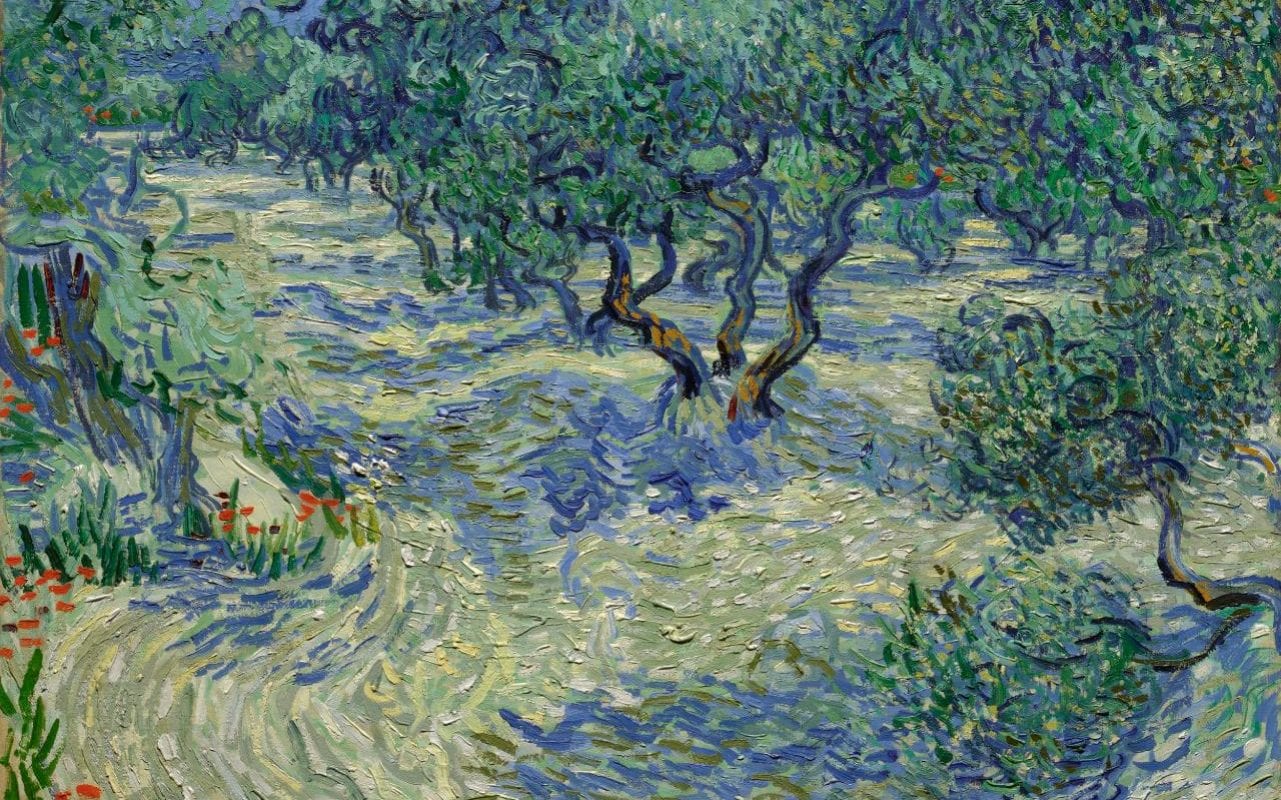

A hapless grasshopper found itself in the news not too long ago because it was trapped, a permanent visitor to a one-painting museum called Olive Trees. You may have wondered, as I did, why notice of this common, elegant insect surfaced. But Vincent van Gogh, a painter many people know, drags any report concerning him, no matter how paltry, into the light.

“What could this be”?

Paintings conservator Mary Schafer may have said this aloud to herself — it’s a lonely job — when she saw that a crust of French rural life was imbedded in the thickly covered canvas she had scanned at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City. Was it a curl of real leaf, buried in the shadow of the tree on the right? No, it looked to be the head of something: a bug. Extrapolating from its size, the body would be about a quarter-inch, but most of it was gone.

What final color did her tiny subject see when it jumped, or fell, into art?

Vincent painted that grove soon after he had, as the modern phrase goes, “checked himself into” Saint-Paul Asylum in 1889. At that juncture, the artist knew full well that paintings were traps.

“But just go and sit outdoors, painting on the spot itself!” he wrote to brother Theo. “Then all sorts of things like the following happen—I must have picked up a good hundred flies and more off the four canvases that you’ll be getting, not to mention dust and sand. . . . ”

You paint outdoors and the outdoors brushes you.

For some reason, I jumped to this image below from a disturbing film of the last century, The Black Cat, in which more than one soul was immobilized not by accident, but by desire. The scent of this stylish nightmare is mustard gas and gunpowder of the Great War.

X X X

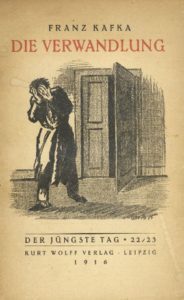

“As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a monstrous vermin.”

Ungeheuren Ungeziefer is the original for “monstrous vermin,” which is unspecific in a way that allows the author to torture his readers with ambiguity. “Cockroach” was an easy leap for hungry and curious tenement citizens on both Atlantic sides, who knew what they were in for, so that’s what Kafka’s character became. Most insects — not vermin — have hard shells, though they crush under fists and heels.

Franz Kafka wrote about visiting the Louvre. He saw a Leonardo, but as far as I know never mentioned van Gogh, whose paintings were elsewhere.

X X X

Mr. Y reached over the gearshift of his Beetle and handed me my first foreign book, a translation of Die Verwandlung, the 1915 novella. I was 14 or 15, Mr. Y’s pupil in a Queens, New York, high school. Because memories themselves go through transformations, I can’t be certain that this volume, which I remember as a gift, wasn’t auf Deutsch and a challenge from my German teacher to up my game.

German’s the language one was supposed to learn in the 1960s if science were to be your field; few New York high schools taught Russian, Sputnik notwithstanding. Mr. Y had heard me mangle easy phrases in class and knew my limitations, though apparently he was trying to change them.

One might ask, as storytellers do, what this Jewish boy was doing in an automobile with the German-born, crew-cutted, slightly chubby Mr. Y, almost 20 years his senior. I can barely picture him now, or even hear his voice, which declaimed Der Schreibtisch is an der Wand and other alien niceties as we sat in his classroom, bored and sweaty. “Herr Vine-Shtine,” he called me, but no more often than he addressed “Herr Koch,” my wax-faced classmate Kenneth, who called me a fairy and wrote the same in my yearbook over my geeky photo with his leaky pen. No relation to the poet.

“Fairy” auf Deutsch? I’m trying to recall the expression on Mr. Y’s face when he asked me, in that same Beetle, on a summer road trip to Harvard with me alone next to him, if I knew what the word “schwule” meant. Of course I didn’t.

He waited a moment and said,

“It means ‘humid.’ ” Then I think he smiled.

His air-cooled car took every rut in the road, bouncing without a care. The good student added schwule to a list of German words he would soon forget — unless he drank too much later on, and much later, when he learned what kind of stuff Berlin’s Schwules Museum had on its walls.

After that full day and evening in the car, so many hours and miles, my usually blank parents suggested that I not see Mr. Y outside of class. They must have known that he and I had gone bowling many times with two other classmates, John and Larry. Our teacher bought the three of us beers and pretended that we had to speak German the whole time.

His hand was on the ivory knob. He gave me a book, trusting my intelligence as my first generous adult friend.

Did that ruddy hand with the thin blond hairs move off onto my thigh, and how much did I want that? Or for him to kiss me. No question mark, no answer.

Nothing Kafka wrote ended happily, but I can’t be sure, because my German studies never thrived, in high school or in college. Although I tried to speak the language I had studied, it stuck in my throat.

I’ve never been to Germany, not even to visit Berlin’s memorial to the Holocaust, in which I learned that one may be caught, in spite of oneself, in a concrete maze, dizzy for escape.

Correction: That comment was supposed to read like this: Thank you, Jeff. I didn’t have any echt-Deutsch experiences until I went to West Berlin for the first time in 1970.

Then, when I worked there in the 1980s, I learned that as if German weren’t a difficult enough language grammatically, its pronunciation is also a challenge: “schwül,” with an umlaut (roughly “schvoohl”) means “muggy” or “humid” or even “sticky,” while schwul, without an umlaut (roughly “shvool”) means “gay” or “queer”. In West Berlin in the 198os, das SchwulenZentral (known as das SchwuZ) was a very popular funky gay venue in a bombed out building which you had to cross plank-spanned craters to get to.