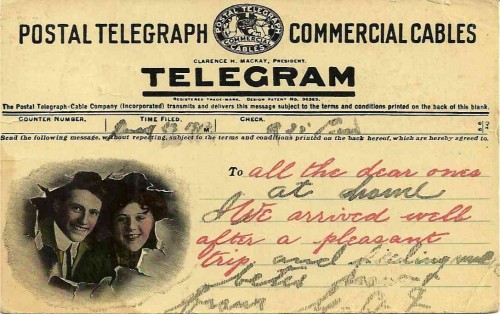

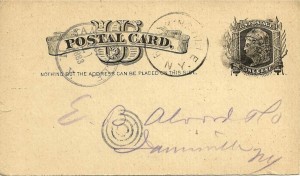

Postcard sticking its tongue out at a rival, the telegram. Sent to Miss Freda Fayman, Hall, West Virginia, June 30, 1913 (all postcards collection of Jeff Weinstein)

Can tweets, texts and email save the post office? Seems a foolish question, same as asking if Facebook or HuffPo could rescue newspapers. Congress has again been going postal about the semi-Thatcherized U.S. Postal Service, on the one hand not wanting to spend a sou to keep it going, on the other not willing to offend business lobbies and scotch that expensive Saturday delivery. Yet there was a time when a similar absurd idea really did work: More than a century ago, the tweetlike penny postcard, enemy to the ostensibly profitable two-cent letter, brought struggling postal services worldwide into the black.

Boomer readers who moan about today’s kids’ texting addiction probably remember their own, equally tiresome grandparents telling them about two, even three, visits from the mailman every day. There were other ways to communicate, of course — oldsters may recall the vaudeville joke “telegraph, telephone, tell a woman” — but letters, they wrote letters, they wrote stacks and stacks of letters. Cursive script was actually taught at school, and anyone who owned a shirt or shirtwaist, or worked for those who did, knew how to remove blots of India ink from starched white lawn.

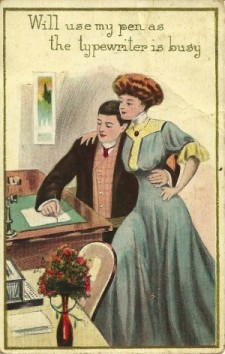

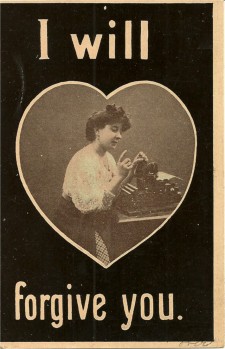

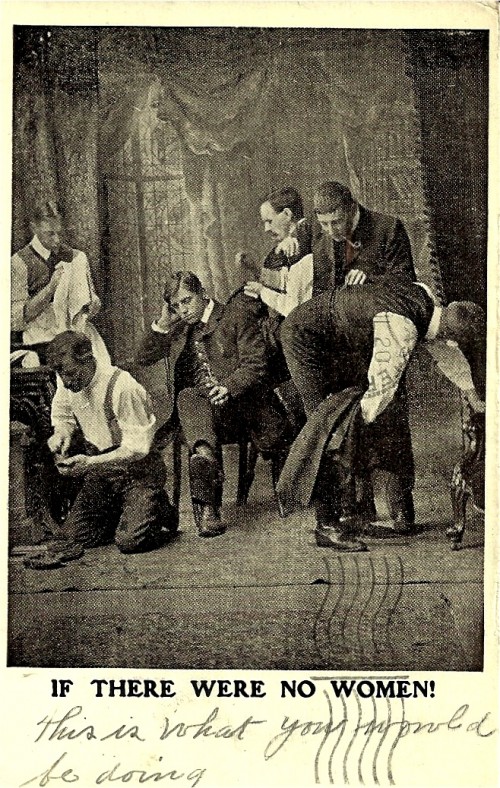

Typing ribbons were messy, too. But at the turn of the last century, a typewriter could be both the worker and the machine, as the punning “working-woman threat to the home” card at far left shows. And in case you think kiddie texting is stupid in a particularly 21st-century way, here’s what’s hand-written on the back of the other card:

Typing ribbons were messy, too. But at the turn of the last century, a typewriter could be both the worker and the machine, as the punning “working-woman threat to the home” card at far left shows. And in case you think kiddie texting is stupid in a particularly 21st-century way, here’s what’s hand-written on the back of the other card:

“Has Rose written to you lately she is coming back and forth again, so we are having nice times together again, and I am very glad she is for she is very nice to go out with. this time for not answering my letter, but I think you might think of me once in a while. Don’t you?

Lurena”

Can’t tell if the card’s target is male or female, but I bet young Lurena and her beribboned friends called the Sears, Roebuck catalog their “dream book” and exchanged fat, leatherette albums filled with the postcards they hoarded.

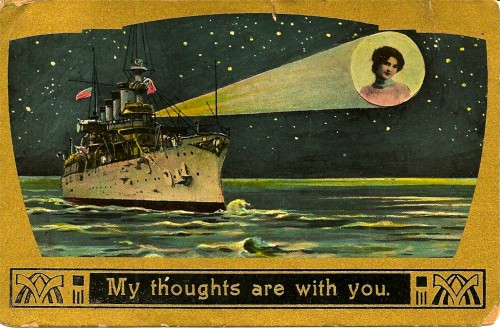

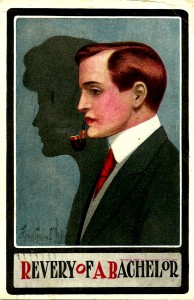

In either case, they wouldn’t have been the only ones actively asking images to create desires — even a desire for more images, which is one way to understand the worldwide craze for picture postcards that started just after 1900 and peaked a few years before the outbreak of the First World War.

A craze? Well, in 1905, over seven billion postcards — yes, a B — were mailed internationally, with almost one billion just in the U.S. Also, deltiologists estimate that about half the cards produced in that period, which they have dubbed the postcard’s Golden Age, were bought not to be mailed but to be pasted in Lurena albums. So those billions are doubled.

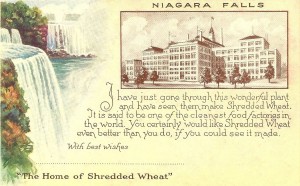

A planet awash in Niagaras, littered with Main Streets, overrun by risque ankles and Peeping Toms. Picture postcards provided the greatest profusion of pictures the world had ever seen.

Oh, what is a deltiologist, you ask? Invented in 1945, the high-rent word, derived from the Greek deltios (a small writing pad or letter), means “postcard collector.”

This writer is one of them. He has worn a T-shirt printed with the words RESTAURANTS and GAY TOPICS to postcard bourses and fairs so that sellers would know just which category of sucker he was.

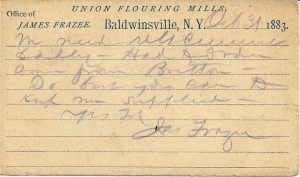

Now, deltiological history is rather complicated and truly interesting only to deltiologists, as our spouses and friends will confirm. In short, advertising and message cards paralleled the rise of postal services from the 1860s on; the struggle between private postals and government-issued blank cards was resolved, more or less, in the 1890s. Austria printed the first color card in 1889, and souvenir and view cards were produced and sent in greater and greater numbers until the economic collapse of 1893 forced many printers to close (my husband just left the room).

The U.S. government tried to regulate private cards, which cost a penny to mail, but finally gave up. In 1899, the first card made of photo paper, the so-called Real Photo Post Card, was sent, and Eastman Kodak saw nothing but opportunity. Think of that first 1900 Brownie as a smartphone, the photo postcard it snapped as a jpeg, the postal system that delivered it as the Internet. A family photo explosion! Staid studio photographers fought to stay alive.

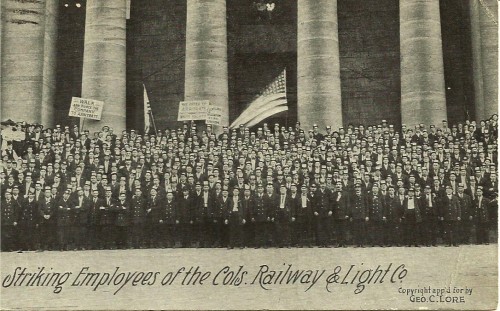

By 1905, real-photo cards were homemade and soulful; German-made chromolithograph view cards of everything from everywhere were lusciously colored; hastily shot and mailed news cards showed industrial strikes and first views of the San Francisco quake; theme and novelty cards were gooey, saucy or slightly insane. Few could resist this thoroughly modern eye candy, and a craze was born, a creative effusion of visual and personal interaction.

No postmark, but undivided back, so pre-1907. Addressed to Mr. and Mrs. S.A. Hendricks, Hermon, Ill.

May 23, 1910 from “your Ant Rose,” Columbus, Oh., to Mrs. Blanche Meyers, Stoutsville, Oh.: “Dear Nease, I will send you a postale of the strike!”

Those frivolous postcard pennies kept postal services everywhere afloat, and history abounds in lessons. Can the USPS find a way to cash in on “digital postcarding” now?

…and so many of these postcard messages were written in fewer than 140 characters, I’ll bet. Interesting too, that the word “post” remains a workhorse in the digital age. Your smart piece makes solid connections.