Normally, my single question to you at the end of this post would be posed via Twitter or Facebook. But so many smart classical-music mavens are my Artsjournal neighbors that I thought I might borrow some of your tidewrack readers for just one time.

Normally, my single question to you at the end of this post would be posed via Twitter or Facebook. But so many smart classical-music mavens are my Artsjournal neighbors that I thought I might borrow some of your tidewrack readers for just one time.

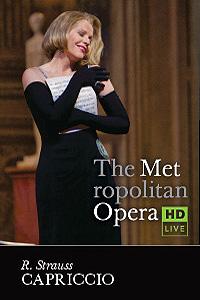

Recently I saw and heard the Met’s production of Richard Strauss’s Capriccio, starring Renée Fleming, at a fairly comfortable, stadium-seating multiplex cinema in Suffolk County, Long Island, New York.

The theater was almost full — and I may have been the youngest customer. I was truly happy that so many of my Long Island neighbors would attend the showing of a somewhat undervalued, orphaned work, thought to be talky and, except for the last “moonlight” solo, not sensational diva material.

I loved every thrilling moment. How beautifully conducted, directed, sung! The witty, valedictory plot illuminates the classic battle of “words or music,” and although Fleming unfortunately channeled coy Ginger Rogers in Tom, Dick and Harry (filmed in 1941, only a year before the birth of Capriccio), the whole experience was almost faultless. Who cared if, supine on a sofa, the star made ridiculous love to a rose?

Yet, good readers, here’s my question. I have no trouble understanding the differences between live and HD-projected opera. Complain about vulgar closeups all you want. Sure, real voice is like real mayonnaise compared to Hellman’s in a jar. I know that, and you know that, but when I’m hungry for it, I’ll have my mayo any way I can. Both kinds of performance are salted with the same tears.

Here’s the thing. I attended this opera movie with a lovely friend, a composer and performer who will travel for hours to hear live anything. You couldn’t find better concert company.

When the last note of Strauss was sung, and the strings and horns faded into nothing, she hooted and clapped her enormous approval.

“Brava! Bravo!” as the cast grinned and bowed on the screen. “Bravo! Brava!” The sound of one fan clapping.

No humans were on that stage ledge; the Metropolitan Opera cast was many miles away. No other audience members, save myself, added to my dear friend’s highly audible delight. All our dour companions in art stood and filed out, silent.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

So, is applause for those onstage, for those in the audience around you who may have shared your pleasure, or for yourself?

I will collect and post your responses.

For an automatic alert when there is a new Out There post, contact me via Facebook or Twitter or email jiweinste@aol.com .

You and your friend were not alone. I applauded too (in a packed Manhattan theater). Why? you ask. It was just a spontaneous reaction; the opera and the production, admittedly not flawless, filled me with delight.

I’ve been discussing this question, among others, with arts producers and movie distributors and exhibitors, and Jeff, your “Out There” piece frames it perfectly. It’s all very new, and applause will probably carry over to on-screen Broadway as producers there begin cinema beams this weekend with MEMPHIS, then move on in June to the Roundabout’s revival of THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST.

From my conversations, I think people applaud the experience, primarily, and not only a particular performance or themselves or each other. We’re now used to focusing on a screen for much of what we see; many of us spend at least as many waking hours looking at a screen as we do looking beyond it. It makes sense that “shared experience” includes watching live performance with others at a screen, and is no longer confined to a reach-out-and-touch dynamic.

This may flip our perspective on what’s actual and what’s virtual, but someone I spoke with at Britain’s National Theatre — in its second season of real-time on-screen performance that brings real applause in 400 cinemas around the world — put it well: Audiences, he said, are responding to live performance that may be an alternative to the real thing, but the experience of watching it with others inside a theater carries much of the same DNA.

Germany has 80 fulltime, year-round opera houses while the United States with four times the population doesn’t have any. Even the Met only has a seven month season. We only have a handful of real opera houses, and they have only partial seasons. In terms of opera performances per year Chicago is in only the 62nd position, San Francisco 63rd, Houston 101st, Washington 121st, and Santa Fe 172nd. The few other companies that exist in America have even shorter seasons. They usually do not have houses and perform in poorly-suited rental facilities with pickup orchestras and singers. This applies even to cities with metropolitan populations in the millions like Atlanta in the 272nd position, Kansas City at 275th, Baltimore at 322nd, and Phoenix at 338th. They are far outranked by even tiny European cities like Pforzheim, Germany which only has 119,000 citizens but occupies the 87th position and thus outranks even our nation’s capital, Washington D.C, by 34 positions. (These and many more valuable statistics are available at Operabase.) Nothing can replace the beauty and grandeur of live opera, but the vast majority of citizens will never experience one. The Met broadcasts, though better than nothing, are a testiment to our second rate nature as a cultural nation.

I’ve attended most of the Met Live In HD telecasts over the years, including a few Wednesday night repeats. It does feel really odd for people to applaud in movie theaters…doubly so for taped repeats. I’ve never done it, but people do really laugh out loud at the comic operas: “Barber of Seville”; “Don Pasquale”; “Le Comte Ory”; “La Fille du Regiment”…so I guess many people feel “if I can laugh, why not applaud?”. I wonder if people will be as reverential for “Die Walhure” next week as those who attend live performances of Wagner.

Sorry to be late to the party, but audiences at film festivals and other venues such as cinematheques and archives often applaud — during credits, and at the end of movies — even when there are no people involved in the film’s production in the room. I’ve even been at screenings where people applaud at the end of particularly well-done sequences, such as the bravura numbers in Busby Berkeley’s The Gang’s All Here. I think it’s the acknowledgement of a shared experience.

I think the size and intimacy of the venue relates to the applause. If your clap will not reach the edge of the stage and the performers could never see you, why bother? Rarely is the experience so exhilarating as to provoke spontaneous outbreaks of applause. I think that applause is a reaction of politeness, or in the case of festivals or rare performances- pure excitement. I live in a smaller town where every performance- good, average or poor- is received with a standing ovation. We are that afraid that they may never return if we do not!