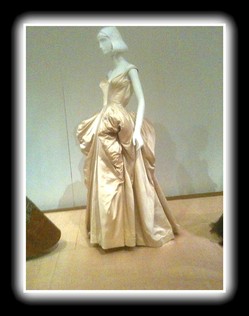

More than 30 years ago, the creator of “Out There” slowly strode down a beach-house staircase in a black-tulle ’50s Balenciaga. It fit him like the glove his then-thin body required, deserved. Never had a shirt or pair of pants supported and caressed him in such a way, as if it were a fabric lover.

Drag wasn’t even close to the point; no hairy surfaces were threatened by the primal relationship between his static carcass and that mobile dress. As he descended, the gown’s original partner viewed her errant garment and its new mate with surprisingly generous affection — she knew intimacy when she saw it. That’s the way fashion relationships work.

We in New York are lucky to have a multitude of special old clothes to look at from time to time, stuck though they are within the dowdy precincts of schools and art institutions. The Brooklyn Museum, longtime closet for one of the most enticing collections of costume and couture in the world, has joined with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in its latest fashion exhibition. The fact of it, however, underlies a sadness, because right now, the proud Brooklyn hasn’t the funds or the staff to care for and display its trove without help, and the collection is now officially part of the Met’s.

Although born in Manhattan, I am a Brooklyn boy and grew up in this museum’s corridors. I dreamt plush, ebony dreams after staring at the design section’s airless deco rooms. Many years later, I was privately shown a wartime Schiaparelli hat, plucked from collection drawers, made of modeled newspaper. Of course, I wasn’t allowed to try it on, but I could imagine. (Take that, Rosalind Front Page Russell.) Not long ago at the Brooklyn, my very own winter coat — the actual one, with a rip inside the left pocket — was the only male piece, the final item, the “wedding gown,” in an elaborate exhibition of Japanese-designed clothing.

Be careful when the critic you read gets older and his eyes yawn — when that heavenly Balenciaga no longer zips.

Youngsters, see the show. Imagine a world in which your background determined what you could wear, when artworks were born at the end of a needle and thread. Think of clothing as language, and what you couldn’t afford, you couldn’t speak.

In spite of my voyeur’s familiarity with the objects on display, a few unfamiliar selections made me vibrate with curiosity and delight. I expect that has to do with their relative lack of allure and unacknowledged, almost defiant, beauty. Here are the reasons I would go back:

A 1948 cotton uniform by the almost unknown Helen Cookman stands in a small back room with two of her other worker outfits. How do you dress servicemen after the war when the only job they could get was gas-station attendant? With military elegance and authority — machine washable, too. And what a laudable risk, to put men’s clothing, gasp, in a show of American fashion.

Oh, how could we omit Schiap’s drag-it-out bug collar, a neoprene study in entomological elegance? But think how much more effective, politically and sartorially, it would be if all the bugs were roaches.

And the hat at the top of the post? So modest, it shrinks behind its feathered betters. Yet whether it be my age or reticent senses, I find that this shy form contains more sculptural flair and plastic pleasure than any piece of raiment in the show. Millinery master Sally Victor made it during the war, in 1943. Truly felt genius.

, 1943-thumb-500x395-15028.jpg)

You are devastatingly right about that hat. It’s both sculpture and architecture. And why do I covet that insect necklace (I have for years) when the very idea of live bugs in my space has me shrieking “Quick Henry, the FLIT!” Odd, I’d never think of you as a Balenciaga person, but rather as a devoted client of early Chanel or Vionnet. I must rethink this. BTW, have you read my “meditation on clothes” Obsessed by Dress”? tt

that men’s uniform was indeed quite delicious… and you’re right, the display did have an air of sadness to it…

Truly felt, indeed. I was reassured to find no faux feelings — or ersatz fabric — here.

Thank you yet again.

Thank you for this exquisite reminder of the time when I worked in the hallowed costume halls at Brooklyn, and Charles James swept into storage and began modeling his magnificent structural garments offering with each pirouette, each flung scarf, a running commentary on the owners, the construction, the times, the intrigues, the patterns.