A Hollywood Pastiche

A Hollywood Pastiche

Although the event may already seem fossil material, the 2009 Oscars were held Sunday in the bloated Kodak Theater at Hollywood and Highland. I recognized the steroided scene immediately, because it’s right around the corner from the deco side-street hotel I stayed at in November, ensconced with that year’s USC-Annenberg Getty arts journalism fellows.

Our small hotel was caught between a tourist behemoth (theater, shopping plaza, lights, lights, lights) and a seedy, winding street abutting rough, treed hills — forestry so close that I was followed early one evening by a companionable raccoon, who was on his way to the mall’s Sunglass Hut for replacements.

Every year I vow not to watch the Oscars, and every year I relent, carping and sighing, congratulating myself when I guess right and belittling the whole old-fart shebang when I’m wrong. If you’re in the industry, there are occasionally real reasons to be upset, as dapper screenwriter and novelist Howard Rodman wrote (on Facebook, natch) about his Saturday attendance as a Spirit Awards finalist for his fine Savage Grace screenplay. Those awards honor independent film, which category is measured, I suppose, by a scale of money. That night, comeback kid Mickey Rourke did win for his wrestling role — he lost the less spiritual prize to Sean Penn the next day — and at the mike the talented tabloid parody of dissolution rambled on, thanking everyone he had ever met, including his dead dog.

Well, almost everyone. I hope Howard doesn’t mind if I lift part of his plaint:

If there were one discordant note, it was that neither Mickey Rourke, who won for best actor for The Wrestler, nor Darren Aronofsky, who directed The Wrestler, nor Scott Franklin, who produced The Wrestler, in all of their separate acceptance speeches, ever once uttered the name of Robert D. Siegel, who wrote The Wrestler.

This was a spec script. This was an original.

I have been, in my life, saddened and brought low by the death of a dog. I understand, and understand deeply, the grief it can occasion. But it still seems wrong to me that Mickey Rourke’s dog, of blessed memory, should have so much acceptance-speech time devoted to him, and the writer of the screenplay without which Mr. Rourke would not be standing there — None at all.

Segue now to a screenwriter who, the next evening, was allowed his place and used it to mark another death and perhaps prevent some more. For a bittersweet Oscar moment, I urge readers to click here.

Just in case, I’ll add some text:

When I was 13 years old, my beautiful mother and my father moved me from a conservative Mormon home in San Antonio, Texas to California, and I heard the story of Harvey Milk. And it gave me hope. It gave me the hope to live my life, it gave me the hope to one day live my life openly as who I am and that maybe even I could fall in love and one day get married.

We identify a dance by its choreographer and a dress by its designer, but a screenwriter’s name is rarely connected to his or her work, which is surprising for a field that brings compressed creativity so close to so many. Let’s give credit, then, where it’s due: The soulful young fellow with his heart on his sleeve is Dustin Lance Black, who won his gilded man for his original screenplay Milk. The more familiar Sean Penn won his man for his portrayal of Harvey Milk, the assassinated gay politico. As he introduced finalist Penn, Oscar veteran Robert De Niro quipped, “How for so many years did he get all those jobs playing straight men?” Timid laughter followed, but the sadness of lost opportunity underlying De Niro’s compliment was apparent to many gay actors and fans.

After the November election, I joined hundreds of midnight demonstrators who had gathered outside the Kodak to voice their disappointment and fury that California’s right of same-sex couples to marry was snatched away. Can you vote on rights the way you vote on films? No, of course not. But to prove how wrong that is, we’d have to pay some attention to our nation’s Documentary category — and we all know how badly those serious people dress.

The next month, the day before Pearl Harbor, my longtime guy and I got married, in Provincetown, Massachusetts. We read Walt Whitman poems to each other at the ceremony, ate as many Wellfleet oysters as possible, and a tiny coconut and lime-curd cake declared us “Married at Last.” That quiet day was much more moving than we had anticipated and, beyond the politics of equality, was without doubt something worth doing, worth having, worth fighting for.

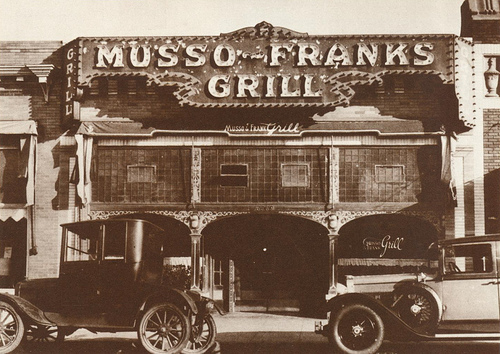

Just a couple of blocks from the Kodak Theater is another Hollywood landmark, less flashy and much more precious. Its early sign read “Musso-Franks Grill” and the present proper name is The Musso & Frank Grill, but everyone who knows “the oldest restaurant in Hollywood — since 1919” calls it Musso’s. The façade is now nondescript, but pull open the front door and you enter a … theater, a theater showing silent pictures.

It’s really a double bill, because the left room is all tall wooden booths and a long counter, the short grill-man behind it pouring and flipping, while in the bar and supper room on the right, the lights dim to allow an equal flapper sparkle of diamonds and martinis. Yes, movie lovers, this is a place that the genius of cinema created, a Hollywood vault in which time gently rests. That fugitive murmur you hear combines the whine of old clocks with layers of ordinary conversation, and the silvery clink behind it is a sound only a spoon in a glass can make.

I sit alone in my booth this Saturday morning waiting for my waiter, who finally brings me the requested pot of coffee. As I sip, immersed in the almost floral staleness of a space that has seen only customers’ costumes change, an elderly man walks in from the parking lot’s elaborate rear entrance. He moves slowly, relying upon his cane, but glides so easily behind a nearby table that I know he has been here before.

He is carefully dressed: pressed khaki pants, a pearl-colored shirt of what looks to be thin cotton, and a rather dowdy derby-brown cardigan. His shoes, not new, have taken a high polish.

After five minutes he’s joined by another man, also in his 80s, equally neat though much more spry. And soon after him comes a third, a bit younger and notably winsome. His socks are sky blue, like Fred Astaire’s.

As I watch, my flannel cakes and bacon arrive. Musso’s flannel cakes are a cross between swollen flapjacks and skinny crepes; they carry a toasted, buttery mouthfeel and faint flourish of vanilla. Flannel cakes were once an American-kitchen staple, but soon they will be gone. Flannel cakes. Flannel cakes. This may be my last opportunity to type those words in present tense.

The three gentlemen are having flannel cakes, too. They’re obviously old friends, close friends, but they speak rarely and without fresh animation — like a married couple, I think, a married triple.

Faint, I take a breath. These cakes are delicious. They are at once the thing, and the memory of the thing.

How can all this survive?

And then I understand for certain what I should have guessed. These three friends have come to breakfast regularly for years, for decades. They may have, in any combination, been lovers, fought over lovers, mourned lovers, hands on shoulders, in all kinds of weather, for better and for worse.

They are, in fact, part of my family, my historical family — exactly what the promise of gay love and marriage, in its past and future forms, is destined to fulfill, and just what we writers will inevitably write about.

For an automatic alert when there is a new Out There post, email jiweinste@aol.com.