This text is adapted from a speech I gave a week after the 2016 elections to a gathering of arts and business leaders at the Creative Industry Luncheon 2016 in San Antonio, TX.

“This is the time when artists go to work. We speak, we write, we do language. This is how civilizations heal.”

This is a quote from Toni Morrison. It has stuck with me. This is our power, and it is immense. But what will we do with it?

Since the election, a week ago, I have been in three different cities. I go from here to another one and, then, another one, and another one. I have had so many conversations about what the election means. Not the partisan conversations—the panicked conversations from people who are on the liberal end of the spectrum, the impatient conversations from people on the conservative end of the spectrum. I mean conversations about what the election showed us about who we are right now and what we need to become in order to be the best citizens and communities we can be.

I was raised in a town in Connecticut where, in my entire high school, there were three people of color. I was raised in a town where the average household income was around half a million dollars a year. I was raised in a bubble and didn’t realize that I was in a bubble.

I was raised in a town where a well-meaning teacher took a Korean girl who was adopted and stood her up in front of the class and, as a lesson cultural diversity, asked us to point out all the ways she was different, and I did nothing. I was raised in a place that allowed me to feel appropriate responding to a homeless person on a school trip that I couldn’t help him because “I only had large bills.” I was so well‑insulated that I look back on some of the ways that I acted and the things that I did and thought and I am ashamed. I live in and with my privilege, and while I don’t let them weigh on me to the point of inaction, it feels important to acknowledge them, and push past them.

Over time, and in large part because of our experience adopting and raising our bi-racial daughter, Cici, I found myself on a personal journey that also then intersected with a professional journey. I became deeply interested in issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion, and particularly issues of white privilege and bias. I didn’t quite understand how I could have moved to through the world for nearly 30 years without understanding the clumsy, privileged damage I was inadvertently doing at certain points in my life.

I found myself, after that experience, working at Americans for the Arts, which is 56-year-old organization that has been dedicated since its founding to the role of arts and culture in healthy, vibrant, equitable community development. It also, as a 56‑year‑old organization, has gone through all of the stages of what that conversation has meant: all of the fits and starts of conversations that were first about diversity, then this idea of inclusion, and then conversations about equity—which have, in one way or another, gone on in our field for the last 50 years or more.

I was asked, among many other things, to lead a department that was charged with talking about the relevance of arts and culture in local communities—which is a conversation you can’t have without talking about equity. It is the thing we hear, over and over, as we have gone into communities across the country and had conversations about what people in those communities see as the role of arts and culture in their lives.

Particularly, at this moment, as we as a country are confronting a tremendous amount of division and trying to understand how we can feel so diametrically opposed to one another, the arts have an integral role to play in helping people find their common ground. We are in a moment where people think they have nothing in common with other people, and that’s not good. That’s why I go from city to city to city and have conversations with folks like you. Because at Americans for the Arts, we believe in the ripple effect of arts and culture. We believe that the arts are an agent for community development. We believe that the arts impact a single person and that single person impacts a group of people, a group of people impacts the community and so on, out in to the world over space and over time. We believe that all the arts should be for all the people. We believe, like Morrison, that the arts heal civilizations and make them whole. That’s our philosophy around arts and culture.

***

But how do civilizations heal? It’s a beautiful sentiment—and it’s certainly necessary—but what does it mean? For me, I think of it happening in nine ways—nine things that are necessary for a community to begin to heal in moments of division. All nine of these are deeply, truly what we, in the arts, do every day. We are the caretakers of culture, heritage, community and creative life. These are our work, and our work is crucial.

- First: the creation of empathy. One thing we know for sure is that arts and cultural experiences actually increase the physical connection between different parts of your brain. That is part of giving people the ability to see things from someone else’s point of view. The more connections you have to an experience, the more ways that you can find some commonality and then walk down that narrow bridge of commonality to an understanding of where they might be coming from.

- Second: the strengthening of social bridges and bonds. When you are in a physical space with another group of people and you were laughing, you were crying or you were experiencing epiphanies, you become closer to the people who you came with. When you were experiencing those epiphanies about someone else’s culture, you become closer to those other people and can understand them more deeply.

- Third: the encouragement of critical thinking. Arts and culture helps people to understand the steps that they need to take to make an opinion for themselves. Arts participation improves how likely they are to go all the way through high school, to go to college, to further their education, which may allow them opportunity to explore a broader view of the world and then assess anew.

- Fourth: the sparking of innovation. Arts and culture are integral not only to bringing innovative organizations into communities, but to keeping those innovators inside organizations happy, engaged and participating in community life. The arts are also feeding innovation itself through the integration of creative practice, the encouragement out‑of‑the‑box thinking, the ability to play.

- Fifth: the creation of a sense of belonging. You need a strong sense of belonging among people. If they don’t feel like they belong then they feel like they are alienated. That loneliness reinforces itself, and leads to hopelessness, and division, and the casting about to figure out who or what has brought someone to this moment. The arts have the ability to provide a sense of belonging. They create a home, as any dorky, lonesome kid (cough me cough) who found his tribe in a theater knows. Our forms and venues also can surface that loneliness to others, and make people more aware of groups and individuals that are feeling disenfranchised.

- Sixth: the illumination of pathways to potential. For certain parts of the population, it is very hard to imagine a world that is different from the world they’re living in. Whether you’re talking about a third‑generation blue collar worker in West Virginia who can’t imagine a life without coal or an inner‑city family from El Salvador who can’t figure out how to step up that ladder and who is met by barriers at every, turn the ability to engage in a creative life, to think about alternative paths through creativity—whether that means actually becoming creative workers or not—is crucial to how we collectively reimagine our paths forward in this country.

These last three are more systematic.

- Seventh: the increasing of participation in civic dialogue. The arts gravitate toward multiple voices. They shine in those moments of messy work, of bringing people together and celebrating difference, of bringing everyone in under the tent, of making new tents. Of dancing together out under the stars when the tent feels too stifling.

- Eighth: the transformation of systems. The arts allow for more opportunities to transform the systems, and boy do we need that right now. We have created a variety of inequitable systems in this country—whether you’re talking about government or public sector, in the arts or outside the arts—and we have to, before we can make any real forward momentum, assess the systems we have and discard or adapt the systems that are disadvantaging the people were trying to serve.

- Ninth: the impacting of impacts. Sometimes, the arts, at the right moment, can help make a situation that would have been inequitable slightly more equitable. Sometimes, at the right moment, the arts can be part of making a good outcome into a great one.

Nine things we need to heal. Nine rudiments of empathy, respect, critical thought, caring, innovation, hope, and opportunity. The arts—that is to say, the artists, which is to say, you—have the ability to make those conversations, and that transformation, happen. These are our responsibility. These are what we need to think about.

Whether you are actively working in arts and culture or you are one of the many people in the public or private sector who is helping to support arts and culture, this is what our business is now. This is what we have to be doing.

Over time, this work coalesced, for us at Americans for the Arts, around cultural equity—a broad umbrella that is inclusive of, and also moves beyond, race, ethnicity, age or educational background. Identity is incredibly complicated, and has many different ways of manifesting and changing over time. As a national service organization, we can’t and shouldn’t try to directly serve everyone at the same time in the same way. In supporting a framework of cultural equity, we look to support you in determining your community’s priorities, and to provide you with the resources and services you need to understand and impact the inequities in your own community.

As election results rolled in and pundits started talking about the great divide between voting pools, I found myself understanding even more deeply why a broad embrace of cultural equity is so crucial right now.

***

A couple of weeks before the election, Saturday Night Live did a skit called “Black Jeopardy,” which featured Tom Hanks, the guest host, as a Trump voter competing against two African American women. In particular, Hanks is playing the trope of a rural, economically disadvantaged, and undereducated Trump voter.

Over the series of questions it becomes clear that in almost all areas, he and the two African American women share a tremendous number of beliefs, desires and challenges. It is not until the button on the skit, when a category comes up called “What lives matter?” that they diverge.

When I saw that skit—which was both so funny and so on point—I marveled, because there, in 3 minutes on a sketch comedy show, was a pretty crystallized illustration of what cultural equity means, at least to me. We have many places of commonality and relatively few places of difference.

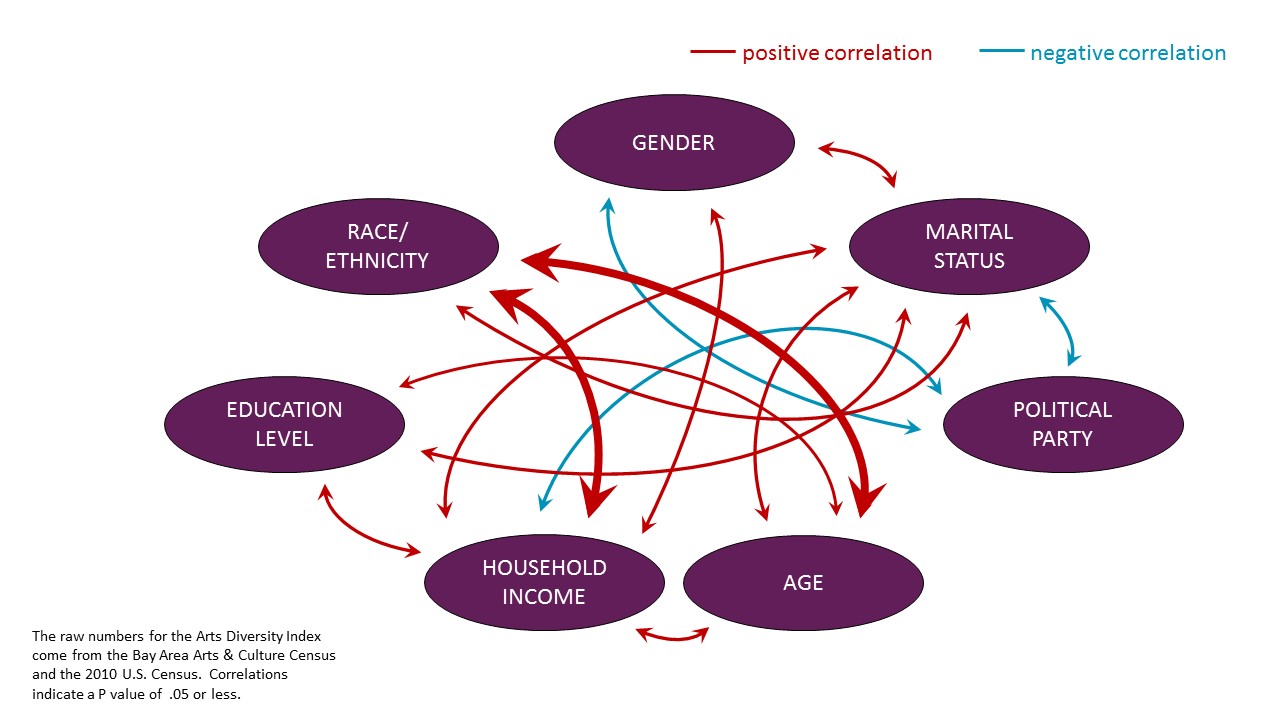

All inequities are interconnected. Any work is making progress for all of the work. Some work I did in 2013 called the Arts Diversity Index proved this. We looked at 750,000 arts attendees in the San Francisco Bay Area and cross-referenced a variety of different demographic categories appended to sales records in order to understand, among other things, how those demographies were related to each other.

What we found was that they’re related all over the place. Any of those red arrows are positive correlations. Anything that looks blue is a negative correlation. To explain, look at the thicker red arrows. Those arrows indicate that, in terms of correlation, if your audience has a broader spectrum of age, then it is also statistically likely that it has a broader spectrum of racial diversity. If your audience has a broader spectrum of racial diversity, then it is also statistically likely that it will have a broader spectrum of household income. And of course vice versa.

If you think about it, that really isn’t surprising. We know that younger people in The United States are more diverse than older people. We know that a broad demographic set in terms of race and ethnicity probably brings in people who are higher and lower house hold incomes if only because some of them are younger, they have less disposable income, and so the story goes.

But there it is, statistics and data, and this supports an intersectional way of thinking that directly impacts the way that we think about what we’re doing. Any act to address inequity is an act to address all inequity.

Each community is incredibly different. Jane Chu, the chairman of the NEA, likes to say, “If you visited one community, you visited one community,” and that is very, very true.

As a national service organization it is not within our ability to know what is going on in your community. You’re much equipped to do that. We want to resource you and help you in identifying and tackling the pressing needs of your community in that moment.

Multiple efforts, pursued aggressively, make more progress possible, in part because that freedom to choose what to tackle brings more people into the fight. It takes a lot of different directions, attacks from a lot of different directions to tackle this. This has been a systemic and ongoing thing for 200 plus years. If we are to collaborate and do our part to try and mitigate and take down some of the systems and to address and redress some of the inequities that have happened over time, it’s going to take a lot of different people doing a lot of different things.

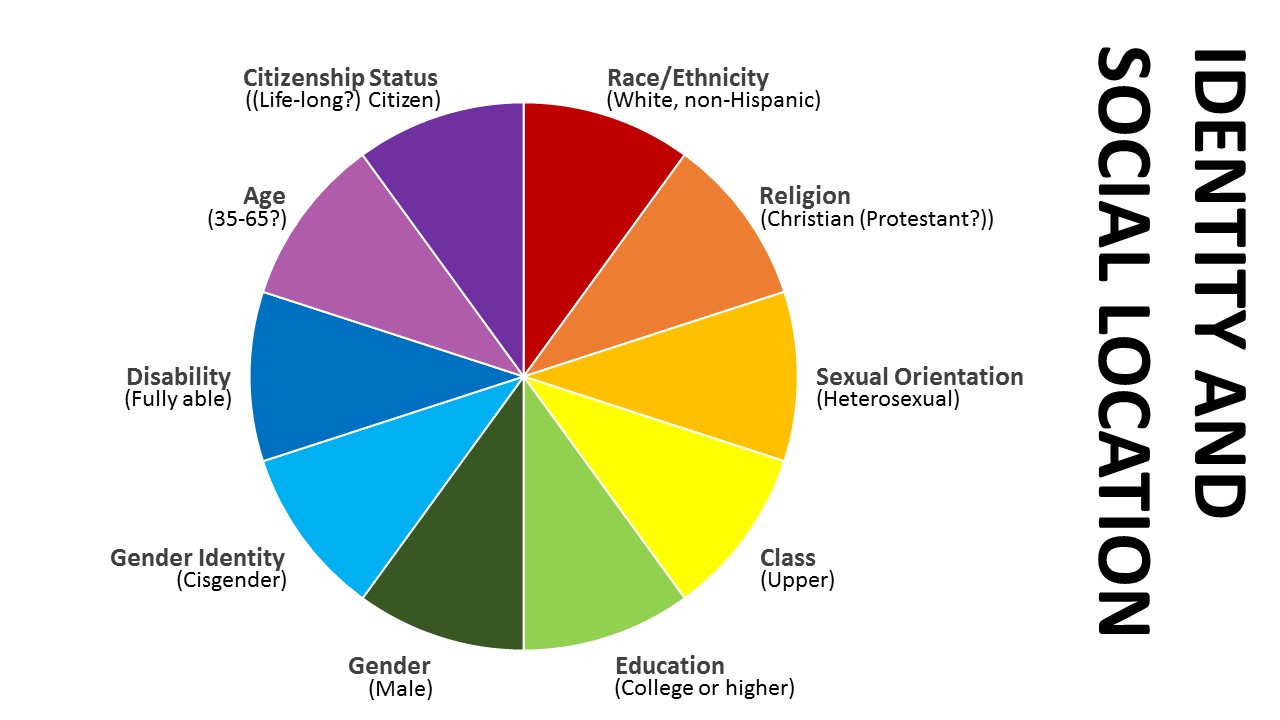

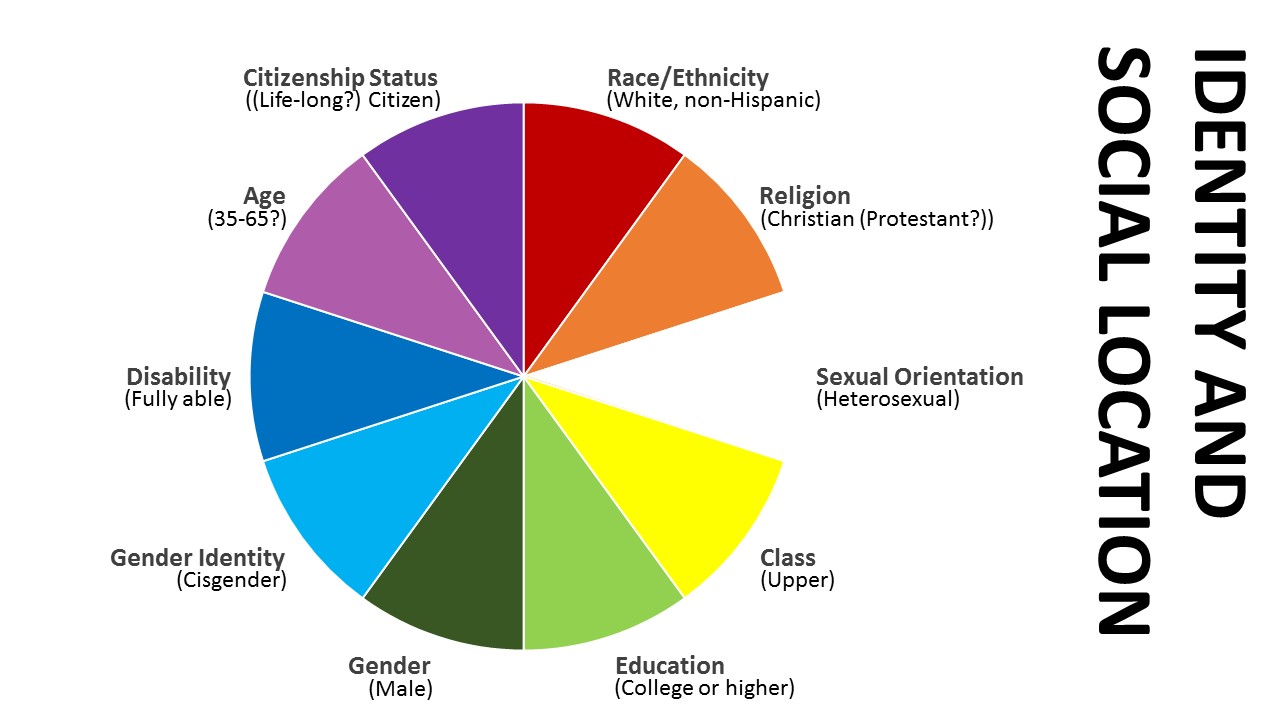

In this intersectional context, I want to touch on the concept of social location and identity. This diagram, based on work by Carmen Morgan of ArtEquity, calls out ten different areas of inequity, and then, in a two-part exercise, helps articulate our areas of empowerment and disempowerment.

The idea is that, for each of the ten areas, you first start out by brainstorming in whatever group you’re doing the exercise with about which group of people is the dominant group in that category, based on access to power. In the context of race/ethnicity, that usually is white people, in the case of gender, it’s usually males, etc. And so on around the wheel. When we did this exercise as an organization, the basic answers we got to were as follows.

Once you have identified these areas, you then begin the process of cross-referencing yourself in all of these spaces. This is what mine looks like:

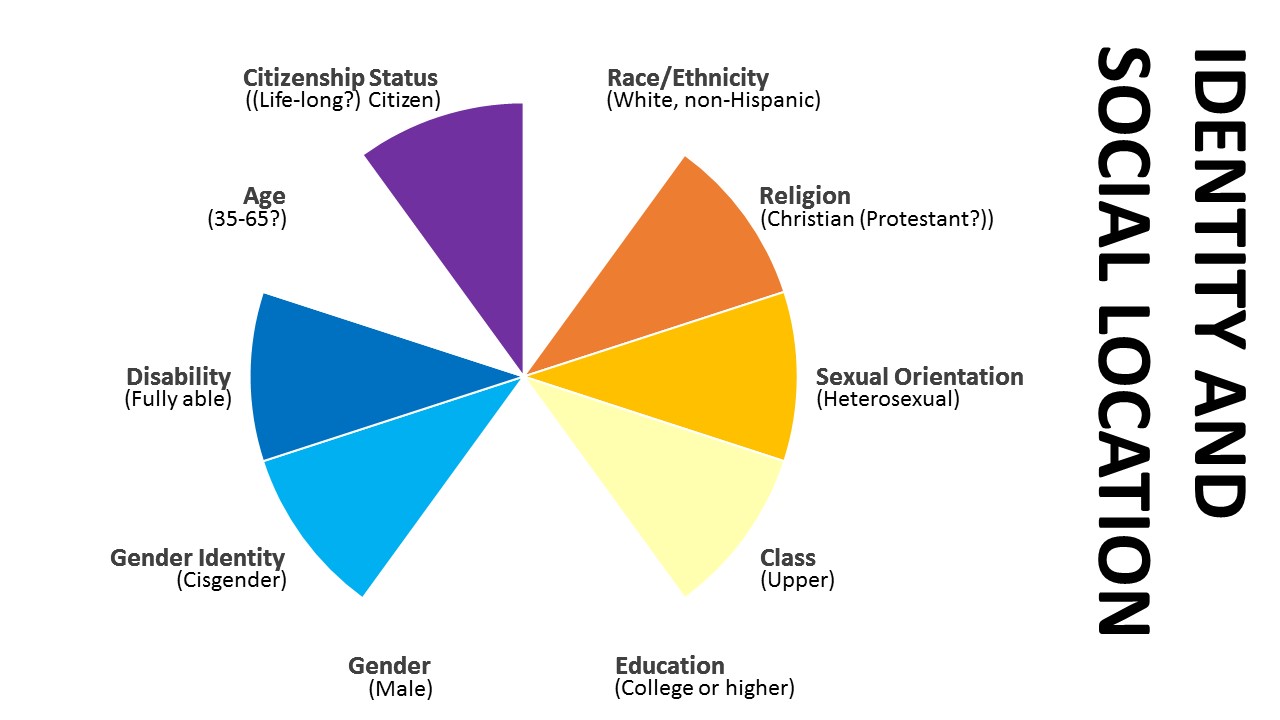

It tells me that I have a tremendous amount of power and I have the ability to use that power to impact the way that other people who might have less power in this context at least go through the world. The reason that that’s particularly personally important to me is that this is what we know about Cici’s pinwheel so far:

Of course, she’s five. She doesn’t know whether she’s cisgender or transgender yet. She doesn’t necessarily know who she’s attracted to. We don’t necessarily know whether she has or will have a disability. It’s potentially possible that many of these pie slices will disappear for her.

It’s an important thing to try and figure out and grapple with as someone who is incredibly privileged. And that microcosm of me-and-my-daughter again can be magnified to a larger conversation. If your organization is extremely privileged, and you’re in a space where there’re people who have less of that power available to them, what are you doing to share that power? How are you doing so with humility and an understanding that you, by and large, are not directly responsible for the privilege you have—your gender, sexual orientation, age, race are all things beyond your control, and any power you gain from them is incidental and unearned. Privileges are privileges—things given, not necessarily earned. How are you using your social location to carry forward an intersectional conversation and create space?

Everyone deserves a full and vibrant creative life, but it is not up to us to tell you what that means. It is up to us to resource you or to resource the local partners that we work with so that they can help make that full and vibrant creative life. Whatever you want it to be.

And so to our responsibility as a field. Our responsibility did not start on 11/9, but it certainly crystallized on 11/9.

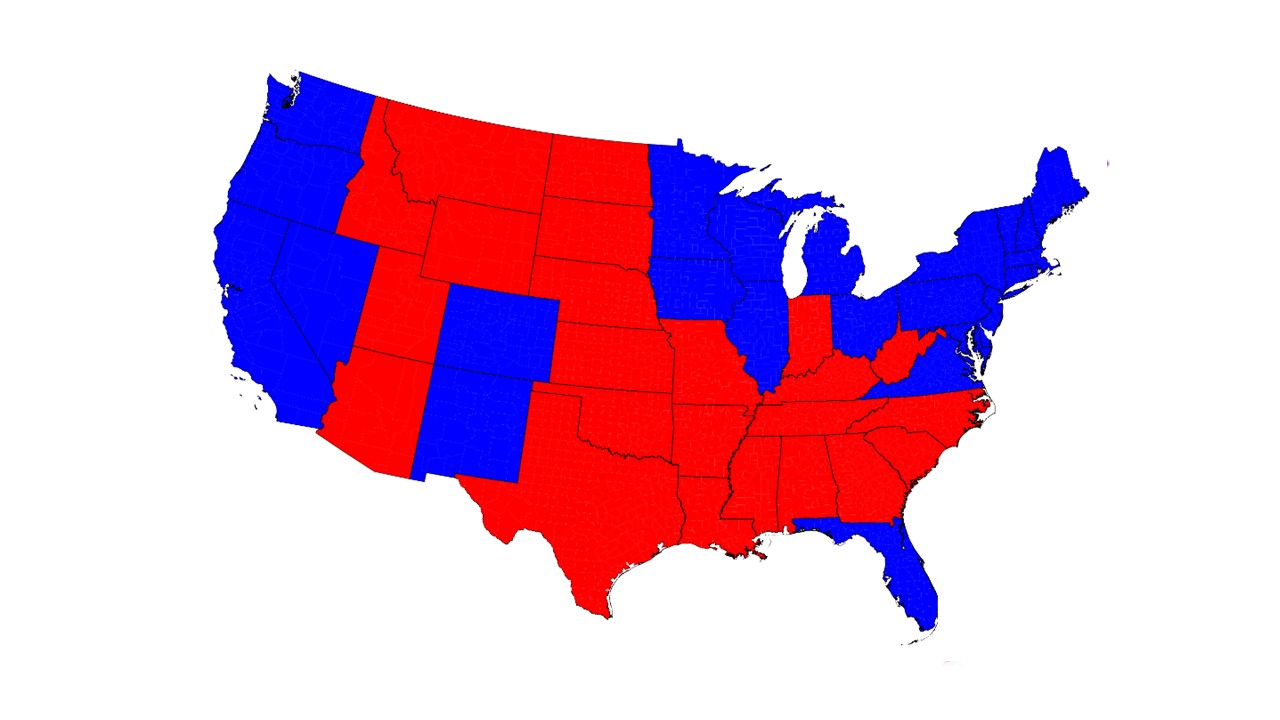

One of the reasons that it crystallized on this day is that we saw a map that looked like this:

And we thought to ourselves, “God, we are such a divided people.”

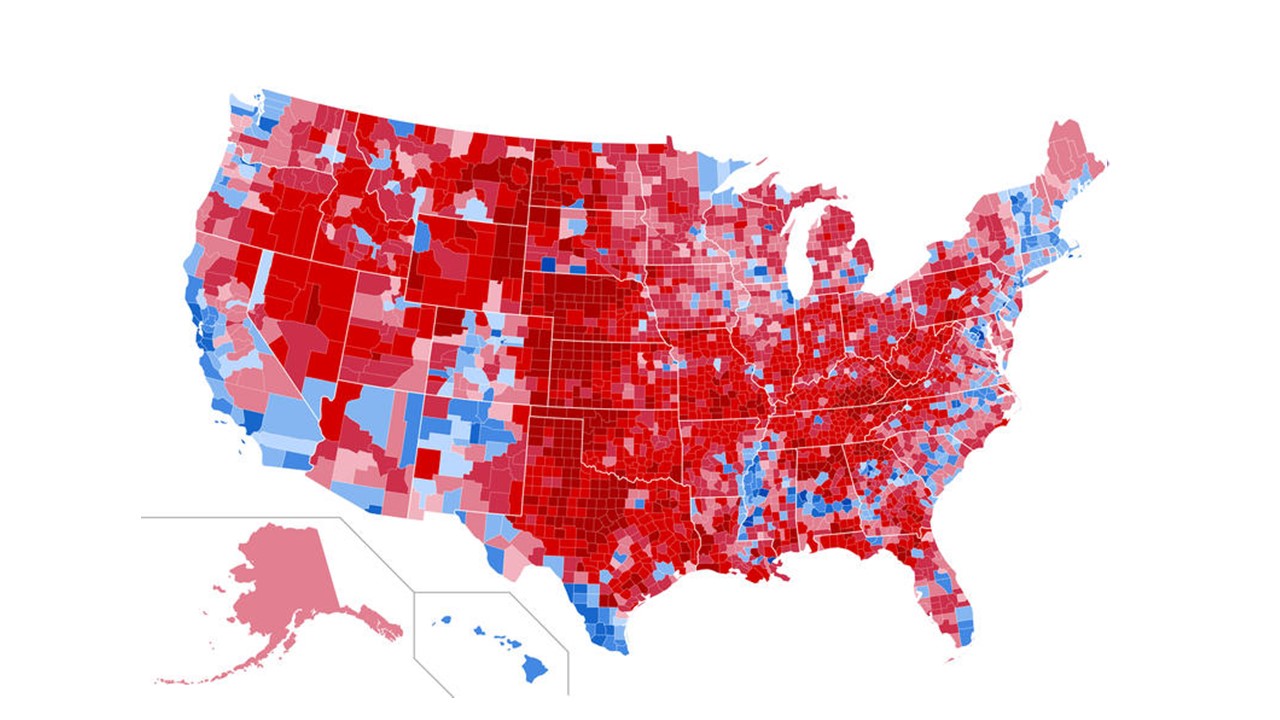

But the truth is that if you break it down to counties, the map looks more like this:

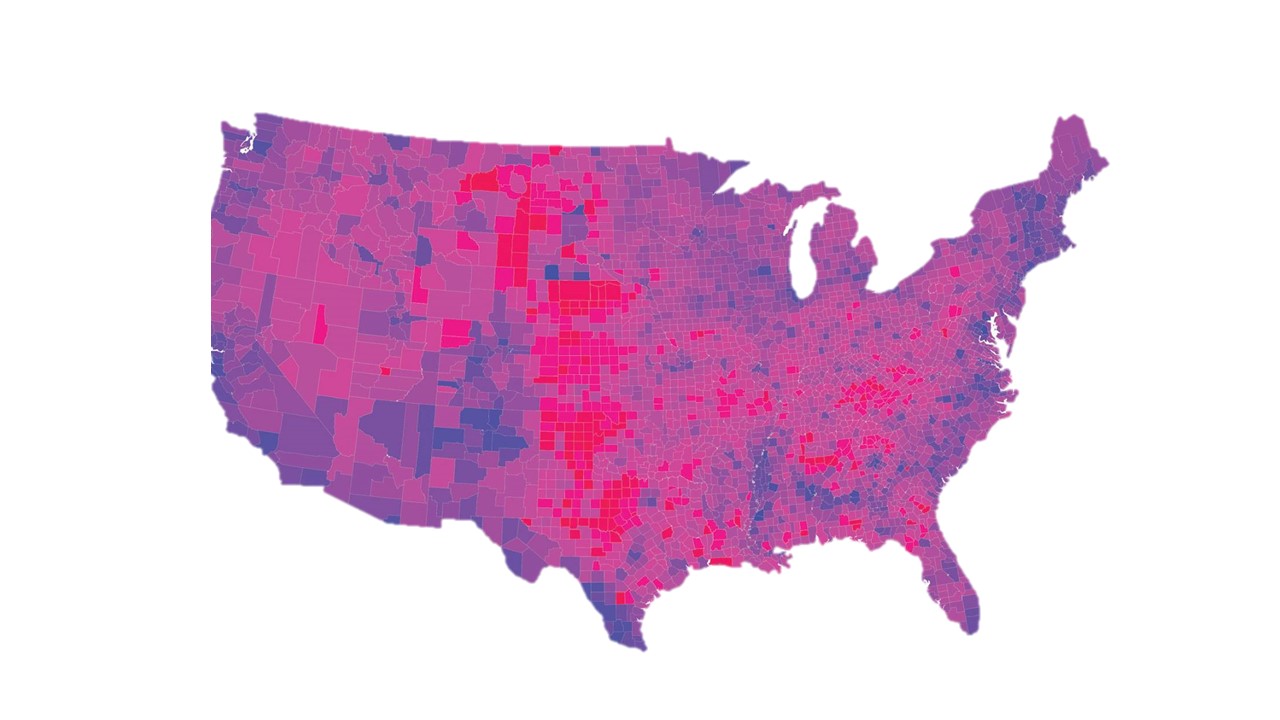

And if you actually take those counties, and you look at every single vote, and you shade them accordingly, then the map begins to look pretty darn purple:

It’s important to remember this: the red/blue divide is not actually the full truth of where we are as a country. That map, and our constructs around it, of division and a lack of common ground and common respect, doesn’t illustrate how close or far apart any two individuals are.

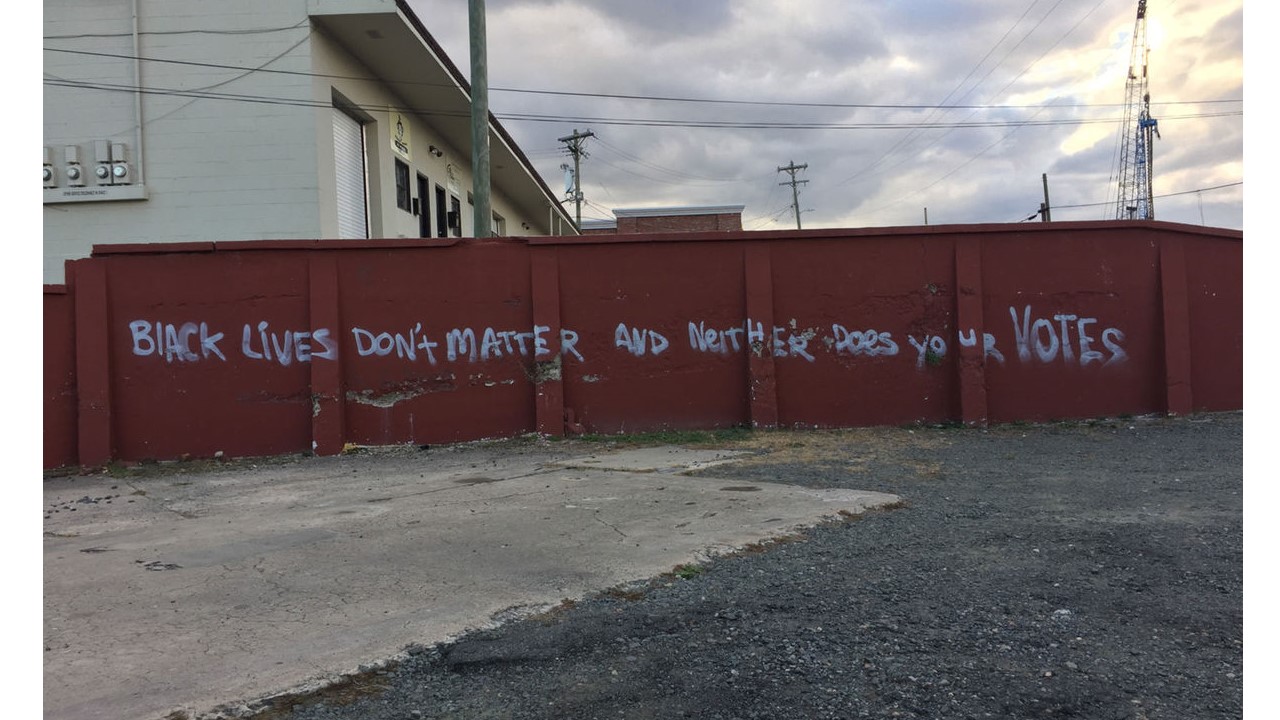

But it’s hard to remember that when you see things like this:

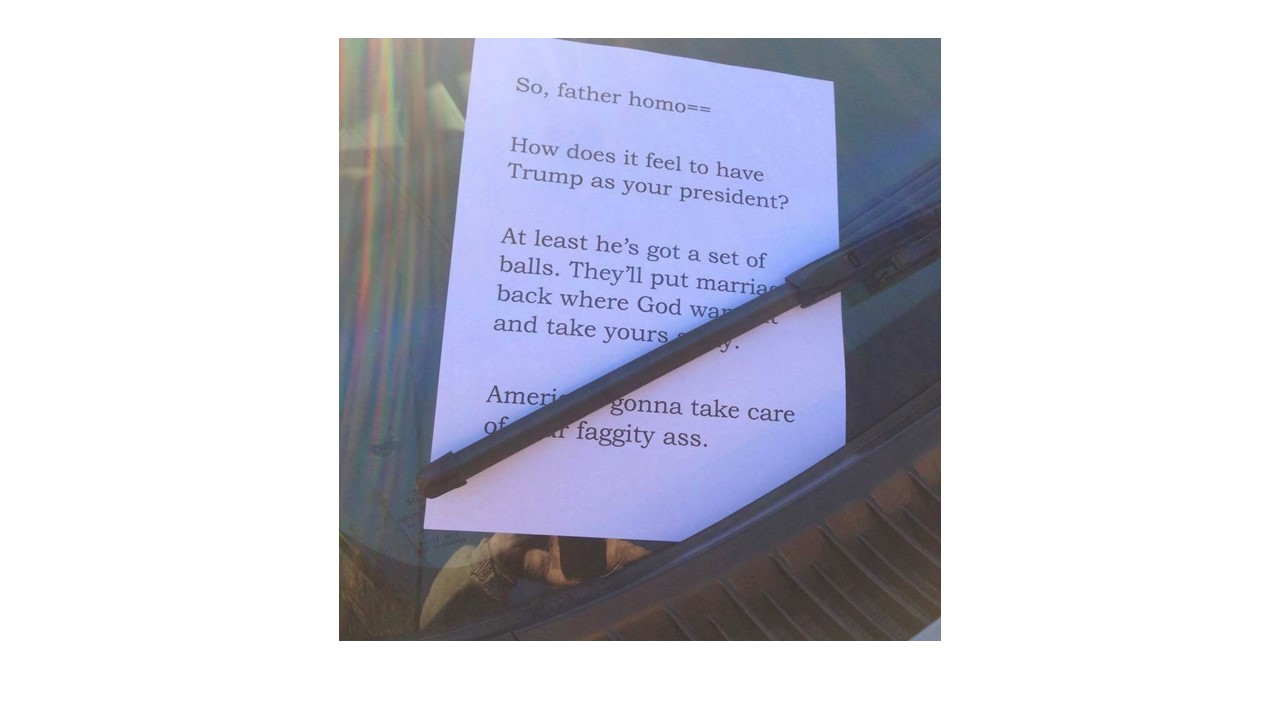

or like this:

or like this:

These images, and the stories of intolerance and hate, give me, as I’m sure they give you, deep pain. They make me want to rage at those people, to run from those people, to reinforce our divide and give up on them. But I can’t, and you can’t.

We have a lot of work to do as a country, and it’s up to us to do a lot of it. We are not so different that we have nothing in common, and we have to dig past the anger to get to common ground–which, just to say it, is not to ignore affronts to basic morals or values.

For me, I come back to Cici, because a few weeks before the election, she said something that has rung through my hyper-liberal household, even on election night as her two parents melted down…

She said, “If Donald Trump wins, it’ll be OK, because we’ll take care of each other.” Then she said, “We’ll even take care of the people who voted for him,” which I thought was very generous.

The lessons our children teach us. The lessons we learn together.

Cici loves superheroes. She loves Spiderman and Captain America and Iron Man. As I traveled in the days after the election, moving from city to city and missing her terribly, I kept coming back to a string of recent nights where she had chosen as her bedtime book a compendium of short Marvel superhero stories. Which are, of course, our modern myths—as fantastical and allegorical as the Greek and Roman tales of the gods. And like all myths, they teach us things we need desperately to learn, if we listen to them. So I listened, in my tiny airplane seat, and here’s what I heard:

- Villains and heroes aren’t born, they’re made by experience. Which is another way of saying that alienation takes a lot of forms. Judgment and blame do, as well.

- Villainy and heroism are strongly in the eye of the beholder. We view the world through our own experience and that’s the limitation of being human.

- Most everyone believes that they act for good, it’s just the definition and parameters of “good” that shifts. Most people, even people whose rationale you can’t being to understand, can probably articulate a path to their version of goodness. And there’s much to be learned in understanding that journey, even if you can never agree.

- Moving into the light (or the darkness) can sometimes happen so slowly you don’t even notice it until you’re there. Transformations take time, but they can also go both ways—we must be vigilant, and patient, and impatient, and strong, and flexible.

- With great power comes great responsibility. The arts are not inherently good or bad, but they are powerful. I’d even go so far as to say they’re a superpower. You can use the arts to do great things, or you can use them, as has happened over the last 50 years and beyond, to reinforce all sorts of terrible systems that disadvantage people and make certain small groups’ lives better. We are at a moment of deciding that.

For us, as a family, and then also as an organization, and as a community, it comes down to, “What are we going to do with that power, and what are we going to do with that responsibility?” And when my faith fails, I think of Cici in a superhero pose, and I recommit to doing good, to building bridges, to leaning into love, compassion, and the good intentions of most people—and in my ability, with humility and patience, to be part of navigating towards that healed civilization Toni Morrison was talking about.

One of the ways that my boss at Americans for the Arts, Bob Lynch, sometimes ends his speeches is by quoting “The Oath of the Athenian Citizen,” which I thought was good, so I totally stole it. This is what it says:

“We commit this city to be, not as good as but better than, not as beautiful as but more beautiful than what it was when it was committed to us.”

That’s something I try and emulate every day, every community that I’m in, with the humbleness and humility that is necessary, and the understanding at the same time that I have a tremendous power to give. May you do that as well—we need your power now more than ever.

Thank you for all you do.

[contextly_auto_sidebar]