In September, in advance of an Americans for the Arts training at the Sundance resort in Utah, I visited Salt Lake City for the first time and met with Caryn Bradshaw of Visit Salt Lake and Karen Krieger from the Salt Lake City Arts Council. We toured the city a bit, and what we saw forced me to confront a bias that I didn’t realize I was harboring—I thought that Mormons must be anti-art.

In September, in advance of an Americans for the Arts training at the Sundance resort in Utah, I visited Salt Lake City for the first time and met with Caryn Bradshaw of Visit Salt Lake and Karen Krieger from the Salt Lake City Arts Council. We toured the city a bit, and what we saw forced me to confront a bias that I didn’t realize I was harboring—I thought that Mormons must be anti-art.

My relationship to the Mormon Church is at once one of long distance and of great personal confrontation. For most of my life, Mormonism didn’t register on my radar at all—I grew up in Connecticut and mostly viewed Utah from above as we flew over it on the way to visit my grandparents in California. When I first began learning about Mormonism, it was through the hearsay of kids talking to other kids about polygamy.

And then in November 2008 my life was quite personally affected by the Mormon Church—a group who had funneled lots and lots of money into California in an ultimately successful attempt to pass Prop 8 and temporarily ban gay marriage. In that moment, what crystallized for me was a feeling that people who would push so fundamentally against my happiness and my rights could not share my passion for anything—that they must have so tilted a worldview as to be my entire opposite. And though I didn’t know it, that reaction settled in me, and became rolled into my overall view of what Mormonism—and Salt Lake City—must be like.

Turns out not so much. In fact, a possible heretical story goes that when the Mormons got to Salt Lake, before building most anything, before building a seat for a government, before even completing the Temple itself, they built a place for the choir. It turns out this chronology is only sort of true, but what is true is that Mormons have, for the nearly 200 years the religion has been around, embraced art for what one scholar terms “the significant role art plays in enlightening and inspiring Church members.”

There’s the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, which is world-famous, but there is also the Church art museum, the financial underwriting of art projects, the annual sponsored art competition, the admonishment to develop personal practice “so that they can tell the story of the Church in art.” Art is everywhere in Salt Lake—in the architecture, along the streets, in the rows and rows of galleries, performance venues, restaurants. According to Caryn and Karen, it pervades the lives of many people in Salt Lake, who cultivate personal practice in a variety of forms. While in Salt Lake, I was taken to a small public art garden nestled between residential buildings. The garden was started informally by some of the surrounding residents and has grown to include an incredible array of sculptures, mosaics, poetry, etc. There’s a whole lot of art in Salt Lake.

But what’s interesting is what that art is…and what it isn’t. The plethora of art in Salt Lake exists, almost exclusively, inside what might be called a strict PG boundary. In the galleries I visited, there were landscapes and street scenes and paintings of cute animals, but there were no nudes, no confrontational pieces, no graffiti or street-art inspirations. Caryn and Karen pointed out to me as we passed the “edgy” theater venue in town, housed on a university campus, which was producing either Spring Awakening or Rent (I can’t remember), and which had been a source of controversy. In talking with Caryn and Karen, which involved more than a little fumbling through my personal misapprehensions about both Mormons and the amount of Mormon influence in Salt Lake, what became clear was that the vibrancy and strong integration of art in much of Salt Lake—into the daily lives of the mostly-Mormon inhabitants, into the passions and habits of folks who likely would never call themselves artists—is able to exist largely because of how well and deliberately that art sits inside the values system of that community.

I had planned on writing about all of this a while ago and got distracted, but it popped back into my head in a big way when I read Howard Sherman’s two posts about the cancellation of a production of Rent at Trumbull High School in Connecticut. Trumbull, as it happens, was maybe a half-hour away from Ridgefield, the town where I grew up, and as many of the towns in Fairfield County are, it was, at least then, a highly homogeneous place—mostly white, mostly wealthy, well-educated. The attitude in Fairfield County, by and large, was not so much conservative in the traditional sense as what I now understand to be a unique combination of libertarianism and WASPish buttoned-upped-ness. There were rules, things you spoke about, things you didn’t, and somehow those rules pervade—an overarching propriety that was only oppressive in the very end, as I awoke a bit to the world, and in hindsight after I left, and that in the moment felt simply safe, calm, and perhaps slightly boring.

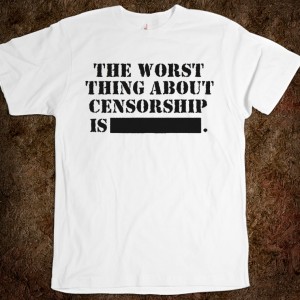

In my senior year in Ridgefield, I was the co-editor of our literary magazine. I graduated in 1999, the year of Columbine, and at some point prior to the shooting that year, we had as a collective voted into the magazine an angst-ridden first-person fiction piece about a kid shooting up a school. In the aftermath of Columbine, with our once-a-year publication already designed, laid out, and about to hit the presses, someone higher up in the administration got wind of the piece and we were told to take it out. We got into an argument with the school board, made our case, lost, and we ran two blank pages and a letter explaining what was supposed to go there instead. At the time, I felt righteous that someone would have forced me to take down art that we felt had sufficient quality to exist, that someone would have censored us so, and the letter we wrote said basically that.

I’m older now. Littleton had seemed a million miles away in 1999, but Newtown is 30 minutes away from Ridgefield. I have a kid now. I have gained empathy. And I understand that sometimes the righteousness of art, the pushing of boundaries, is not the right response.

In the case of Trumbull and Rent, of course, there is no gross tragedy looming behind the decision to cancel the production. There are cries of censorship, of the oppression of ideas. There seems to be a tremendous amount of suspicion that the community, or the players in that community directly involved, might have shut down the piece because of personal values—homophobia, Puritanism, whatever. And I don’t know whether that’s true or not. And I should say that Rent had a profound impact on me, and I was lucky enough to see it many times, and it changed how I viewed myself forever—so I’m not knocking the importance to a closeted kid in Connecticut to see that up on a stage.

But perhaps simply because I grew up very near there, very near a place that (having now lived quite a few places) is extremely peculiar in its protection of a sort of Mayberryesque perpetual lull, I actually find what the principal wrote as justification very interesting and perhaps even progressive. You should read it (bottom of Howard’s post), and I think it’s important to understand that the letter itself may be spin rather than true intention, but taking it at face value, it sounds like the director of the production decided to produce it without really talking to anyone about it, that Trumbull, like Ridgefield, continues to have a faction of people who find some of the themes in the show inappropriate, and that the principal’s reaction was (and I hope I’m reading this right) basically “let’s shut this down now, and let’s figure out how this can be produced later with a lot of context-making activities and conversations to help people understand why it’s being produced then.”

I find very little wrong with that sentiment, assuming it’s accurate. I don’t, for example, find it censorious – I find it, given the climate, rather liberal. In a town like Trumbull, I’d imagine that a high school musical Rent without appropriate context would serve a much smaller and more incendiary purpose than it might if placed in a larger conversation, where more people could have more nuanced conversations about what it means, why it’s relevant, and where the artistic desire to push outside of comfort aligns with the community’s desire to adhere to certain values.

Diane Ragsdale recently wrote a(nother) amazing piece about want and need on her Jumper blog. Reacting to it, Scott Walters wrote, on his Facebook page, about how many of the comments seemed to be knee-jerk reactions against what Diane said—which was, basically, about whether it’s always necessary to be working from what the community “needs” (which is often interpreted as what the artist thinks the community needs) versus what it “wants” (which is often interpreted as safe and within bounds). What Scott said (and he and I are, it turns out, rarely in agreement, but this is one case) was: “Hint to artists: it’s not about you.”

I think that one of the big, big problems we have today in terms of arguing for the value of art to society is that much of the art that is created is presumed to have value for the fact that it confronts society. And I should said I don’t have anything against art that confronts me, confronts my beliefs, makes me think and engage, makes me upset. But I also am a particular kind of person.

We have a conservative problem in the arts. In the Bay Area, per the research I did for the Arts Diversity Index, 15.5% of the total population identified as Republican and only 2.2% of audiences did. Daniel Jones has written quite eloquently on Howlround about the lack of conservative voices in theatre. And before simply writing conservatives off (either political conservatives or something folks who are more conservative in the general sense), we need to understand that both from a service perspective (the desire to serve all) and from the pragmatic perspective of someone who would love a little less political will to be directed against publicly-funded art in America, this population that is not being respected represents a huge chunk of the total people in this country.

Being a censor, like being a bully or being a racist or being a bigot, is a charge that comes with a huge stigma. It implies malice, intention, and a strong desire to oppress. I have to believe that there is a gradation between that level of intention and one that says instead, “Did we think about what this community wants from its art? If we go outside of that context, did we provide a bridge for them to follow? Did we do our due diligence to help a community with certain values to see our point of view, or did we simply get frustrated when our art wasn’t welcomed?”

What if it hadn’t been Rent? What if instead it had been a religious play, or a play about gays burning in Hell, or a play celebrating the Nazis or the KKK or whatever group doesn’t represent a hyper-liberal world view? I mean, for all of its incredible messages and its uplifting structure, Rent is a play about sex, drugs, poverty and death. I’ll tell you, rightly or wrongly, that those were four things that went on the zip-the-lips list in the years I lived in Connecticut.

How can we say that we’re interested in creating a culture where art is celebrated for what it can be at its best—something that both reflects and stretches a society forward—if we don’t allow that sometimes a piece of art might just not fit into the values, mores, and beliefs of a particular group of people? What is the point at which it is better to not be invited to the party than to tone down the colors? What are the consequences of that?

Clay: I think this is a terrific, thoughtful post and every point you raise is worthy of deep consideration. I will say that as someone who has been in communication with many people in Trumbull as the RENT situation played out over the past week and a half, I am somewhat less sanguine about the principal’s statement, but at this point will have to watch and see what happens over the next year. In my prior writing about situations like these (they are all too common), I have always avoided the term censorship, since schools do indeed have the right and responsibility to consider what is read, heard and presented under their auspices. Where I take exception is that these theatre incidents always seem to crop up once the process of putting on the show is underway; in this case just a couple of weeks away from auditions, with faculty pre-production complete. In too many cases, high school theatre is ignored by the administration until there’s potentially “problematic” material, at which point the supervision can become onerous going forward. In Trumbull, it’s worth noting there was a vocal community response in support of the production, and limited opposition; it was the administration that was against the show, apparently not the community itself. As always, labels of liberal and conservative are far too limiting, since one’s opinions are rarely a binary choice for every possible topic. This case is (or should be) about art and education, not politics and the language of oppositional forces. Oh, and I grew up about 15 miles from Trumbull too, just over the county line in Orange CT. Again, I applaud the context brought to the discussion.

Thank you for your thoughtful blog on this matter. Your insights on the Mormons and art are especially appreciated.

In his letter, Principal Guarino does not specify his objections to Rent or why it is unsuitable for young people. Instead, he says it “presents challenges – both in context and execution.” He does not describe or even name what these “challenges” are, which is why observers have filled in the blanks with conjecture.

Your belief that Rent is “about” sex, drugs, poverty and death is your opinion, but it’s not the principal’s. In his letter, he said “Rent is an important piece of American musical theatre. It presents educational opportunities for our students, staff, and community members to explore themes like acceptance, love, and responsibility.”

Those three themes are nevertheless outweighed by “challenges,” and the fact that the director didn’t talk to the principal. There is no way to know what this means. The fact that Rent won a Pulitzer Prize, was a long-running Broadway hit and has been performed by other high schools were not factored in. Nor was the fact that 2/3 of the students at Trumbull High School said they supported the show.

This was all too much to work out by Spring.

He says, “I truly believe that successful and supportive schools are those that nurture strong relationships between the school and its community.”

Yet he did not nurture a relationship by appearing in person at the school board meeting to discuss his decision to cancel. Instead, he sent the letter, a poor example of the “open communication” he claims to want.

He says he is “committed,” not to a future production of Rent, but to “developing a plan” for one. No timetable is given, what the plan would need or who would create it. More as this “develops.”

While he hides behind vague language and surrepetitious actions, the students have behaved far more impressively. They have not engaged in strident rhetoric; they have held no protests or sit-ins, or put up banners and carried signs. They asked for a meeting with their principal (and to his credit, he gave them one).

They also set up a Facebook page to garner support within their community. It attracted attention outside of Trumbull from people and media all over the country, including Howard Sherman and The New York Times.

Censorship carries a stigma because it stops the flow of ideas. An ongoing debate is whether young people should have access to ideas, either by receiving or expressing ones that others, including adults, find distasteful or controversial. This debate pre-dates the Trumbull controversy and will continue after it’s over.

Theater itself promotes the open communication that Principal Guarino claims to want. But what he appears to favor is closed communication, inside strict guidelines, like those you described in Salt Lake. What he has decided, in the case of Rent, for this year, is no communication – the shutdown of the show entirely.

What he hasn’t been able to shut down is the social media and media debate, which is raising all the same questions he hoped to sidestep with his letter.

If Rent was going to lead to controversy, the principal wanted to end it quickly.

Instead, he made it bigger.

While some see the cancellation as a triumph of censorship, it’s a victory of sorts for the students. They put their best foot forward, showing themselves to be respectful and mature. They are a model for how to act in similar situations. If all the world’s a stage, they truly are some of the best actors we have.

They won’t get to do Rent, but they’ve already given us an inspiring example of “La Vie Boheme.”

The principal in Trumbull never really explained why he made the decision to shut down “Rent” so very late in the process. Only in late November, for some inexplicable reason, did he feel the need to shut down this show. Students were encouraged to audition for “Rent” in school announcements made daily for the first two weeks of the school year. It was not as if anyone was trying to keep it secret that “Rent” was going to be the school musical. The choice of the school musical has always been made made solely by the faculty advisors who work on the show, not by the principal. “Rent (the School Edition” has been done without problem elsewhere in the region. And students read “Rent” in at least one class in school without there being any problem. I hope the kids get a chance to do “Rent (the School Edition)” in the future.

The concepts expressed here center around the utilization of art with terms like want and need. To this is added the idea that art should be contextualized through educational activities. The danger is that these views can be reductive. They sounds strangely similar to some of the concepts of the East Block’s Social Realism. In my 40 years of being an artist, I’ve never heard even one say he or she was creating an art work because people “needed” it. And I’ve seldom met any who think its all about them, as one commentator said. In fact, these terms and descriptions not so subtly sets up a contemptuous view of artists as self-righteous pontificators. Good artists are deeper than that and I suspect many would find terms like want and need applied to their work’s purpose and position in society as reductive to the point of being somewhat silly.

Are we seeing once again the perennial paradigm that many arts administrators harbor a vague contempt for artists?

Educational activities designed to stress certain messages in art can also be reductive – and once again sound a bit like Social Realism. Good artists often create metaphors whose exact purpose is that they are open to interpretation. In the case of children, we might need the principal to tell them what to think, but is that a paradigm for society at large?

By defining art in terms of want and need, there is a hidden or unconscious implication that they should be defined by their relationship to the marketplace. I think that is why I see this sort of discussion often raised in America, but almost never see it in Europe, (where I live about 8 months a year) and where capitalism is more strongly mitigated, especially in the arts.

I notice also in the discussion on Ms. Ragsdale’s blog, that the views often (though not always) breakdown along two lines, those held by administrators, and those held by artists – in the rare cases where artists even bother to enter the discussions. The general reaction of the artists often seems to be that the concepts expressed by administrators seem too simple and pat to capture the truths about art’s relationship to society.

Do these differing views define the perennial conflicts between artists and administrators? Must they? Do the practical concerns of administrators and the inability to devote themselves fully to artistic creation lead to more superficial understandings of art? Or is it really true that artists are selfish people who think its all about them, as one commentator said?

Our society has been damaged by the false notion that beauty is in the mind of the beholder. This slogan of personal taste has become a rallying cry for the rights of political and social groups, communities and even states to be able to judge, censor and determine what art will be.

We are losing our knowledge about art and replacing it with our opinions about art.

The destruction of the NEA, for example, is the history of ultra conservative religious/political individuals such as Don Wildmon and his American Family Association putting pressure on television stations to censor shows like Archie Bunker. This conservative witch hunt grew to the national political spectrum and the cultural war against the arts began and continues to this day.

This cultural war has grown and become so successful that we have a new language and value system shaping in regards to art. It is increasingly unacceptable to value the new and the unexpected in what artists produce, a quality that is at the core of what modern art is about. Instead of elevating new artistic vision we say we should canvas the wants and needs of the community. Instead of promoting the fundamental aspect that the arts lead society into new and uncharted realms, we are politically led to believe that good art is that which engages and includes the community and allows them to participate in the formation of the art which they want to see.

The need for any type of social censorship of art disappears if you can control the production of art. This social/political shaping is evident in the continual defunding of the NEA and the reformatting of their programs from the artistic to the social. We as a nation no longer fund artists directly, we fund creative placemaking. We don’t fund the production of art, we fund art organizations, which interject a new more local level of control over cultural production. Arts organizations are the new breed of censors, the new gatekeepers of the socially acceptable.

Social censorship is also evident in the requirements of major private and foundational funding sources which more and more now demand projects to include the neo-liberal language of engagement and participation.

This is social/politcal censorship of the worse kind. It’s the political changing of an art based on visionary anarchy and genius to a art dictated by those dominating society, a changing to an art that is shaped not by artists but by the personal opinions of a majority of beholders.

All very true and well stated. I wonder why the arts management community is not addressing these issues. Why do they so strongly conform to the neo-liberal language and agendas you describe? Is it because arts management training in America is situated in business schools that generally subscribe to neo-liberalism? Or is it because arts managers cater to wealthy board members who are well served by neo-liberal economic policies? (Though not all wealthy people support neo-liberalism.) When asked about these seeming biases, why do the arts management folks present on ArtsJournal generally remain steadfastly silent? Would open and clear stances against neo-liberal concepts possibly damage their careers?

Richard, I totally get where you are coming from. The dangers you speak of are limitations placed on artists that I as an artist resent deeply. I’m glad you spell this position out and draw some of the connections. I agree that things seem to be trending in this direction, and I too am uneasy about it.

There are two points I’d like to address that relate to what you are talking about. The first is that while the trends you indicate seem to be deeply embedded in the bureaucracy of arts institutions and pertain especially to the broader funding of individual artists and independent art projects, its only part of the story. Perhaps. Its certainly the story of institutionalized art. But I wonder how much art still lives outside these pressures and ‘rules’. I wonder if the picture of the situation you paint is truly an issue of survival for ALL the free artistic expression we both cherish. I wonder if the things we value can still live, and thrive, in the margins of institutionalized art offerings.

So while I too am discomfited by the trends you are talking about, I’m not sure that its a question of either/or. I simply hope that there will be room for all of these various agendas within the broad spectrum of the arts. My question is whether seeing the value of independent artistic values means we can’t also acknowledge the role that art DOES HAVE in the community. And if you go back not even very far to the roots of art in society you will find that it has always been connected to the expression of a society’s values. The Modern individualist conception of the arts is just a blip on the radar, and its not certain that it has replaced the old social version as much as it has claimed the right to exist by its side.

So we are justified in defending that. I just think that we need to choose means that promote all art rather than one at the expense of the other. Even if, as you point out, that other seems to find its own advocacy at the expense of what you and I value. I’d like to see both prosper, rather than either/or. We simply need to be careful not to throw the baby out with the bathwater. A narrow conception of the meaning and value of the arts is always an insult to the diversity that art does and must embrace. Human creativity is not limited to these partial agendas…. And artistic value is not contained completely within them either.

My second point is that these bureaucratic pressures are simply one of several outside factors that defeat the independent intentions of artists. I think we both agree that our own intrinsic motivations as artists are what we value most. But I’d point out that an artist who attempts to make a living from their art always faces the influence of those who control the purse strings. If you are marketing to collectors or to any niche of the public, just what does that mean? A market context is not an intrinsic quality…..

When our intrinsic motivations are subjected to the pressures of making a living its not always the case that they remain pure. The temptation to play to the market is a perpetual danger, and its one I’m as deeply concerned with as I am worried about the institutional pressures that threaten our creative virtuosity.

And I’d say that these extrinsic influences can creep into our work unannounced. For example, I have been bothered by the mythology of an artistic ‘voice’ or signature style that is often promoted as necessary for an artist. If we truly were engaged in the free expression of our ideas, why would we ever think we needed to have one dominant means of expression? The truth is that this is how we best get paid. The larger art world and collector dollars often attach themselves to reputations and to iconic identities. It ends up mostly being less about the individual artwork as a creative manifestation and more about how it fits in the broader context of an artist’s lifework or a movement within the arts themselves. Shouldn’t we hope that our art can be valued in and of itself, rather than simply being justified by its place within the arts context? Just how do our intrinsic motivations align with these outside expectations?

Artists often end up fleshing out only these limited expressions of their imagination because to step outside of that would violate the expectations of their audience. This is an unnecessary and avoidable restriction of an artist’s creative freedom, wouldn’t you agree? And yet artists bend the knee to it all the time. And this really bothers me! Not that they do, but that it seems necessary. Since when are the consistency and coherence of a body of work the primary virtues of creativity? It seems entirely fascistic to make that case.

So the point I’d add to what you discussed is that these outside and extrinsic pressures are deeply embedded within the artist’s experience. Its hard to say which is worse. Individual artists obviously still thrive in obedience to these pressures, and if it works for them, who am I to argue? What concerns me is when it gets promoted that this is the only way of doing it. That its the ‘right’ way of doing it. I am hopeful of a pluralism where all these different virtues can live shoulder to shoulder.

I would say that ‘needs’ and ‘wants’ are important roles for art to fulfill in a community. But they are not the only virtues. We can do other things with art. Equally important things, I hope. Its my desire that the conversation opens up honestly and equitably to the many faces of art. Its as wrong to pretend that intrinsically motivated art is irrelevant as to dismiss extrinsically motivated art as unimportant. Can we do justice to all conceptions of art? Is that too much to ask?

Richard is not arguing for a one-sided, either/or perspective, but against it. There are obviously many approaches to art and its relationship to society. Richard notes that the American ethos over the last 30 years has strongly trended toward stressing entrepreneurship over other approaches.

Andrew Horowitz also discusses this in a recent article in the Guardian:

http://www.theguardian.com/culture-professionals-network/culture-professionals-blog/2013/dec/05/artist-as-entrepreneur-american-dream

Horowitz’s article has a couple errors. Stressing entrepreneurship in the arts in the US did not begin in the 90s, but rather in the 80s as part of the ethos of Reagan’s neo-liberal economic philosophies. And his assertion that the European public funding system for the arts is being replaced by an American system is not confirmed by statistical data. Most continental European countries still reject the American model.

Carter,

Your premise that art “has always been connected to the expression of a society’s values” is wrong. It’s true that historically art reflects the societal values of the time, but that doesn’t tell us why art was made the way it was at that time. The dominating religious art of medieval times didn’t reflect the desires of the people on the street as much as it did the religious control of art by the church. It was a hierarchical, top down, control of what art was and how people were allowed to think about art.

It’s not till we reach the Modern age that art, science, philosophy are freed from the controlling influence of religion and the state. And, thankfully, we still are under the influence of modernistic thinking that says it is the artists that lead society forward in our cultural endeavors. Every great creative endeavor that has had a profound effect on society has come from the individual and in the field of the arts that creative individual is an artist.

I am not suggesting that artist don’t have economic and social pressures that effect their creativity. What I am asking for (to bring the discussion back around to Clayton topic) is a reassertion, a re-recongnition by arts organizations, funding foundations, and state and federal arts agencies of this very fact: that it is the artist you should be representing and advocating for.

Hell yes it’s a “question of either or”. I don’t want any part of any art world saying they support artists when in fact they don’t. Here in Michigan, according to the Pew Data Project less than 1/5 of all the money that is funneled through the states art organizations ever ends up as programing, that is money that goes to the artists to pay for a performance or an exhibition. The rest goes to organization real estate, salaries, employee benefits, advertising etc. Yet most people think there tax dollars or donations goes to support or foster “the arts”. I don’t want a society that says we value the arts, that says the arts are a priceless part of our human development, but we then provide little to no financial support to our cultural institutions and the artist producers of our society.

Let’s understand how we got into this mess. Let’s work harder to understand the political forces that are controlling the dire straights of the arts today. Let’s be more clear on how we define wants, needs, and not only censorship, but the control of artists.

“Every great creative endeavor that has had a profound effect on society has come from the individual and in the field of the arts that creative individual is an artist.”

In the world of the mind, there is for the most part, no such thing as a completely autonomous individual. We are all an expression of our culture to a considerable degree. And more specifically, almost all artists were strongly influenced by their societies and community of artists, both past and present.

Your view that funding should focus exclusively on artists is what produced the current and equally extreme focus on community.

Have you ever noticed that censorship and dogmatic positions seem to go hand in hand? Richard, you sound remarkably like a censor! The call of ‘freedom of expression’ sounds a bit hollow when its not also the freedom to express society’s values. Is there an inconsistency there? Hypocrisy? Any kind of bigotry treads a line between promoting its own values and denigrating the values held by others. Its a line we should step well clear of, in my opinion. And its not often a position that raises sympathy for our cause. That too seems worth thinking about……

Clayton’s post raised what I feel is an important distinction: The difference between censorship and just saying “No”. Both you and I want to advocate for a place where artists can act independently of outside concerns, where art is made from intrinsic motivations. There needs to be space for that, and in the margins at least there always will be. But Clayton’s post is addressing the situation from an audience’s perspective, and it would be difficult to maintain that all good art is made without some intersection in the public sphere. In other words, some of it may still be purely intrinsically motivated, but some also may have extrinsic motivations. You cure cancer by aiming at the cure for a disease that affects millions of people. Art that moves people isn’t always an accident…. We can TRY to make a difference. Even blazing the trail can be socially motivated.

Artists are often subject to the preferences of the audience and broader community anyway. This was the theme of Clayton’s post. And that influence can come as sticks and as carrots. In the extremes of censorship we see big sticks being wielded. In declining audiences we see smaller yet still potent sticks being waved. Its voting with dollars. The carrots, of course, are all the perks and rewards that our audience sways us with. If they like what we do we have incentive to continue doing it that way. That’s how we get fed. What’s not to like about carrots? And unless we are hermetically sealed off from outside influences these extrinsic preferences WILL impact us. Sticks will beat us, and carrots will nourish us.

The difference between saying “No” and censorship is a matter of degrees, but its also a different kind of activity. One aims to speak for itself, the other to speak for everyone at once. I think we both want to live in a world where artists are given carrots rather than beatings. To me that sounds inclusive rather than exclusive. Why does it sound like you can’t wait to get your hands on a stick and dole out your own measure of ‘justice’?

And yes, Richard, the historical influence of Religion on art is a social influence on art. The ‘top down’ pressures you describe are the top of society downwards. It seems difficult to argue that religious institutions are not a part of society and that any influence they exert is not also an influence of society on that society…..

The only extrinsic influences that are not in some way social are those of the natural world (perhaps) and those of discrete individuals (minimally). For, as William points out, we humans ARE socially constructed beings, and what we think will always have a social dimension to it. Even, it can be argued, our intrinsic motivations……

And that does seem worth thinking about……

It’s not the job of artists to express the “values of society”. That result might be propaganda, it might just be pandering, it could be mass marketing, it might also be kitsch, but one thing it’s not is art.

An artist’s work might end up being about a articular value that society exhibits but it shouldn’t be consider an artist’s “job” to do so.