About a year ago, Theatre Bay Area got a small grant from the California Arts Council that allowed us to investigate how the diversity of the Bay Area theatregoing population differed from the diversity of the general population. That report, I’m happy to say, finally comes out this week. Below is an abbreviated version of the executive summary–the full report is available for free on Theatre Bay Area’s website. To see all of the infographics created out of this research, please click here.

Diversity is not new as a conversation topic to Bay Area arts institutions; the pressure to diversify has existed for quite a while. In the Bay Area, this pressure manifests most strongly in the form of foundations, trustees, patrons and employees at Bay Area theatre organizations either implicitly or explicitly letting these organizations know that the diversification is increasingly a requirement, and the lack of it is increasingly untenable.

There are many difficulties in being in that position. Diversity is a tremendously complicated issue, even as tackling it is crucial to the field’s continued relevance. In order to make a conversation about diversity meaningful and actionable, the conversation conversation must be:

- Informed by data.

- Backed by research from both inside and outside the arts field.

- Bounded by standardized benchmarks and goals.

- Inclusive of the idiosyncrasies of each organization while also understanding that those idiosyncrasies do not constitute an exit from the conversation.

- Understanding of the short-, mid- and long-term potential consequences, positive and negative, of an arts organization or an arts community trying to truly expand the diversity of their leadership, staff, art, artists and audiences.

The Arts Diversity Index is a response to the dual simplicity and complexity of diversification in the arts. Conducted from November 2012 to April 2013, The Arts Diversity Index provides an in-depth analysis of over 500,000 attendance records of theatergoers in the San Francisco Bay Area from 2006 to 2012. These attendance records, drawn from the Bay Area Arts and Culture Census, were appended with a variety of demographic information, and were pulled from 25 theatre companies ranging in size, geography, age, board size, annual budget, etc, and representing, as much as possible, a breadth of diversity in what is admittedly a single narrow part of the larger arts sector. Those 25 companies were also then examined using data provided by the California Cultural Data Project to understand whether certain company characteristics might relate to fluctuations in diversity.

BASIC DIVERSITY PROFILES

All told, this research project examined seven different types of diversity in theatre going audiences, and compared those diversity scores to the same diversities in the general population as drawn from the United States Census data for the five Bay Area counties in which those theatre companies performed. The types of diversity examined were: race/ethnicity, age, household income, gender, educational attainment, marital status, and political affiliation.

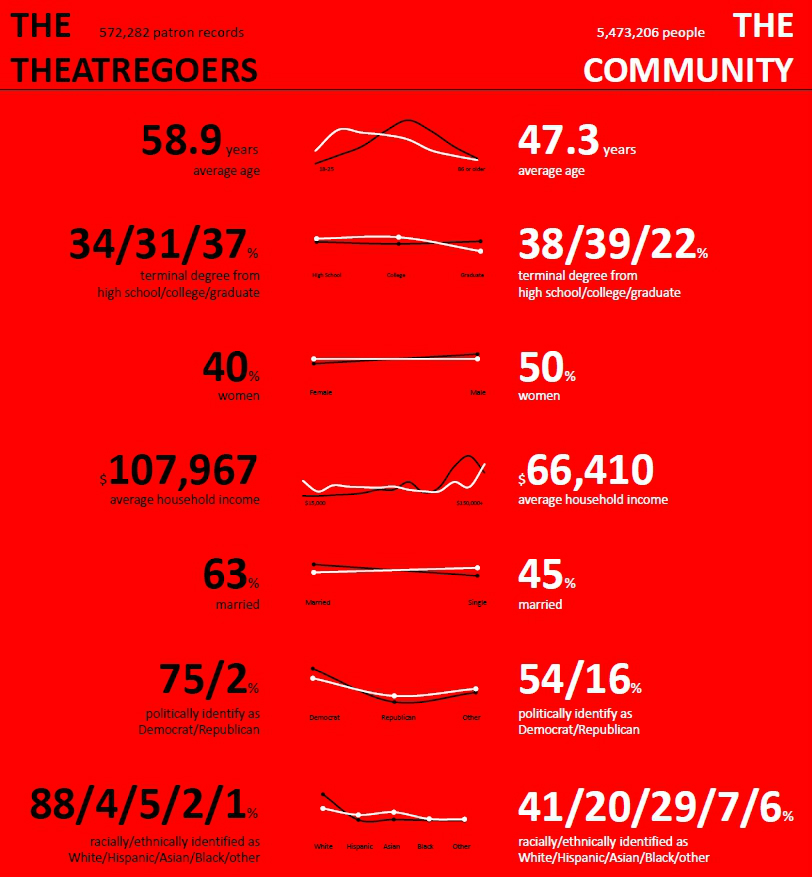

- In aggregate, the “average” theatergoer in this sample had a 9-in-10 chance of being white, a 6-in-10 chance of being male. He was likely a registered Democrat, age 59.3 years and with 65% likelihood of having a college degree. He also had a 1-in-3 likelihood of also having a graduate degree. His household income was $109,167.

- In comparison, in aggregate, the “average” member of the general population in the five counties sampled had a better chance of being non-white than white, and was equally likely to be male or female. He or she had a 1-in-2 chance of being a registered Democrat, age 48.1 years and with a 60% likelihood of having a college degree. He or she had a 1-in-5 likelihood of also having a graduate degree. His or her household income was $75,080.

Using the Arts Diversity Index, a new mathemathical equation that takes a particular type of diversity in a population, for example age, and converts it into a score between 0 and 1, index profiles for each company and county were created for all seven types of diversity. In the case of this study, the goal was to understand not how a company might diversify as much as possible (i.e. total parity), but instead to understand how a company might mirror the larger population in which it existed (i.e. the company’s home county). The population profiles from county to county were examined, comparing the general population of the theatre company’s home county with the theatre’s patron population. The disparities between these populations, while consistent in direction throughout the Bay Area, are markedly different from county to county. Most of that disparity, however, has to do with differences in the general population not the theatergoing sample—the theatergoing sample is remarkably consistent in profile regardless of county, while the county populations themselves are variable.

While certain Arts Diversity Index scores for theatregoers were very far from the similar scores in the general population, others were comparatively close. In order of disparity, theatregoers were farthest from reflecting the general population in terms of: race/ethnicity, then household income, political affiliation, age, marital status, gender, and, finally, educational attainment.

In terms of race/ethnicity, theatergoing audiences are nearly 90% white, which is more than double the prevalence of whites in the general population of the Bay Area counties studied.

The average household income for the theatergoers in the sample was $40,000 higher than the average household income for the overall population in the counties studied.

Politically, the majority of both the theatergoing population and the general public in the five counties studied were Democrats, although that majority was much larger within the theatergoing population than in the general population.

The average age for a theatergoing patron is more than 11 years older than the average age of the general population in the five counties studied.

Seventeen percent more of the theatregoing audience was married than the general population in the five counties studied.

Gender diversity of the theatergoing population was almost at parity, on average, with the gender diversity of the general population.

In terms of education, fifteen percent more of the theatregoing audience had a graduate degree than the general population in the five counties studied.

To view a county-by-county comparison of the theatregoing audience and the general population, please see the infographics here.

In general, given the baseline diversity characteristics of the theatregoing audience, getting theatregoers’ Arts Diversity Index scores to more closely align with the scores of the general population meant:

- Race/ethnicity: an increase in non-white attendees.

- Age: an increase in younger attendees.

- Household income: an increase in less affluent attendees.

- Gender: an increase in female attendees.

- Educational attainment: a decrease in attendees with graduate degrees.

- Marital status: an increase in single attendees.

- Political affiliation: an increase in non-Democrat attendees.

INTERCONNECTED AND ADJACENT DIVERSITIES

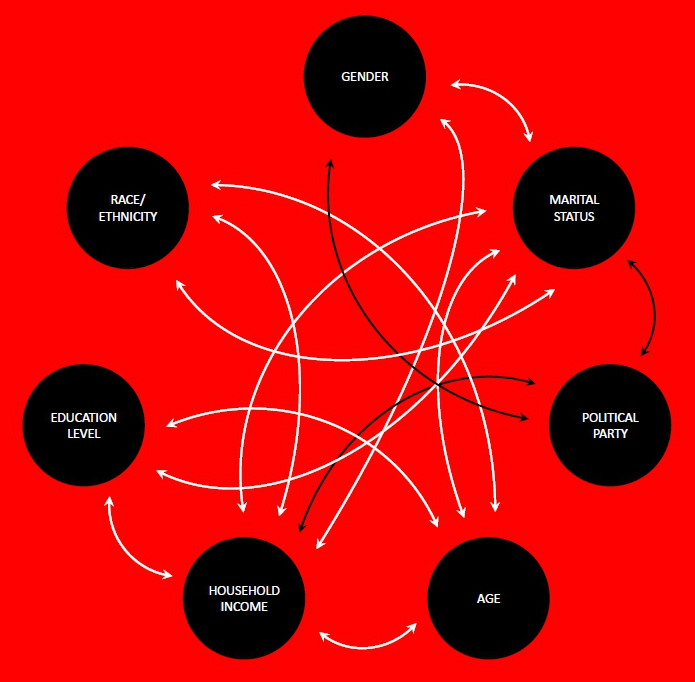

The relationship between theatregoer Arts Diversity Index scores for different types of diversity were examined to understand correlations between types of diversity. Statistically significant correlations of various strengths exist between 15 of the 21 possible combinations of diversity, most of them positive (i.e. an increase in one type of diversity correlates with an increase in the other type). Some significant correlations include:

- Increased household income diversity is correlated with increased age, gender, race, educational attainment and marital status diversity (i.e. economically diverse audiences are also likely to be younger, more female, more racially/ethnically diverse, less educated and include more single people).

- In addition to being correlated with increased household income diversity, increased racial/ethnic diversity was also correlated with increased age and marital status diversity (i.e. racially/ethnically diverse audiences are also likely to be younger and include more single people).

- Increased political affiliation diversity was correlated with decreases in household income, marital status and gender diversity (i.e. less Democratic audiences are also likely to be wealthier, more married and more male).

In the above graphic, white lines indicate a positive correlation (when one type of diversity increases, so does the other), while black lines indicate a negative correlation (when one type of diversity increases, the other decreases). These correlated outcomes illustrate a highly interrelated reality of diversification, and point to the possibility of tackling issues of diversity through multiple channels at once. Because some of the Arts Diversity Indices for audiences are farther from the index scores of the general population than others, some issues of diversity might be viewed as more actionable. Index scores provide baselines and benchmarks for such action.

INTERCONNECTED AND ADJACENT COMPANY CHARACTERISTICS

In this study, in order to test out the ability of the Arts Diversity Index scores to be used as guideposts for providing possible strategies forward, California Cultural Data Project from the twenty-five companies was cross-referenced with the diversity data. The purpose was to see if those characteristics were correlated with changes in diversity index scores. Company characteristics examined include: age of company, company home county, total annual budget, total number of board members, percent of revenue that was earned, percent of expense spent on marketing and communications, and average adult ticket price. Statistically significant correlations of various strengths exist between 9 of the 21 possible combinations of company characteristics. Significant correlations include:

- The age of a company is positively correlated with the total annual budget of the company, the number of board members at that company, and the average adult ticket price.

- The season year of the data (i.e. “the 2005/2006 season”) was not significantly correlated with any of the other company characteristics (or, incidentally, with any variation in diversity).

- Percent spent on marketing and communications was not significantly correlated with any of the other company characteristics.

CORRELATIONS BETWEEN COMPANY CHARACTERISTICS AND ARTS DIVERSITY INDEX SCORES

In an attempt to understand whether there are particular company characteristics that potentially have impacts on diversity (or at least with which statistically significant differences occur), statistical tests were conducted, and 22 out of 49 possible correlations were determined to be statistically significant. Significant findings include:

- The age of the company correlated with fluctuations in all types of diversity except for educational attainment. Companies under 10 years of age and companies over 50 years of age were likely to have more men, more wealthy people and more Republicans in their audiences than companies in the middle age range.

- Very young companies (under 10 years), along with companies in “middle age” (20-50 years), were found to have more age diversity (i.e. more young people) in their audiences than their other counterparts.

- The very oldest companies–which also, given inter-characteristic correlations, means the largest companies–were the ones that demonstrated the most racial/ethnic diversity.

- Companies with larger budgets had more racial and age diversity than their other counterparts.

- Companies that had an average adult ticket price of under $10 or over $60 had higher rates of racial/ethnic diversity than other companies.

- There were a variety of diversities where the home county of the company correlated with differences in diversity. Age, gender, marital status, political affiliation and racial diversity all varied in statistically significant ways based on home county, in some cases mirroring the variations among the general populations of those counties and in some cases not. Audience age diversity, for example, varied based on county, but generally followed the trends of those counties—so the oldest audiences, by and large, were found embedded in the oldest general populations. Similarly, counties with more political diversity in their general populations were the home to the theatre companies whose audiences also had the most political diversity.

- Except in Marin County, which had both the least diverse total population and the least diverse audience population in the study, theatergoing audiences did not mirror the relative diversities of the home counties of the companies. All of the county-level audience numbers were much less racially diverse than the general populations of the counties, but they varied unpredictably. Alameda county, for example, had the most general population diversity (66% non-white) and the second-least audience diversity (11% non-white).

CONCLUSIONS AND DISCUSSION

This pilot study provides a first step towards a variety of potentially fruitful future conversations. While deeper and more complete data would likely provide a richer picture, the calculation of the Arts Diversity Index and its pairing with various characteristics of arts organizations to see what affects change has the potential to truly augment the difficult conversation around diversification and the arts. The data reveal both a path forward and a set of caution signs along that path. Diversification is as necessary as it is complicated. The nature of our audiences, as homogenized and unrepresentative as they may be, is interwoven deeply into our structures, and such tangles must be taken into account.

By analyzing the relationship between types of diversity, we can begin to understand what manageable, incremental, least-disruptive changes and strategies can be implemented in order to begin to tackle the problem. In so doing, we have the potential to both move from simply “valuing” diversity to actively “managing” it, and to do so with a pragmatism that will allow that management to happen at the expense of short-term stability.

ABOUT THIS REPORT

This report was commissioned by Theatre Bay Area, one of the largest regional arts services organizations in the United States, with funds provided by the California Arts Council and the California Cultural Data Project. It was produced with data support from TRG Arts and the California Cultural Data Project. Analyses were conducted by the author with assistance from Dr. Seth Miller of the University of California, Davis. The identities of the twenty-five theatre companies examined in this report have been kept anonymous. The author and Theatre Bay Area greatly appreciate their participation in the research.

[…] been blogging about for a while is finally out; an abbreviated version of the executive summary is here. Five-word version: all the stereotypes are […]